The Cosmic Serpent (13 page)

Read The Cosmic Serpent Online

Authors: Jeremy Narby

“Ouroboros: bronze disk, Benin art.” From Chevalier and Gheerbrant (1982, p. 716).

Mythical serpents are often enormous. In the image from Benin, the Ouroboros surrounds the entire earth; in Greek mythology, the monster-serpent Typhon touches the stars with its head; and the first paragraph of the first chapter of Chuang-Tzu, the presumed founder of philosophical Taoism, describes an extremely long fish, inhabiting the celestial lake, that transforms itself into a bird and mounts spiraling into the sky. Chuang-Tzu says that the length of this cosmic fish-bird is “who knows how many thousand miles.”

3

3

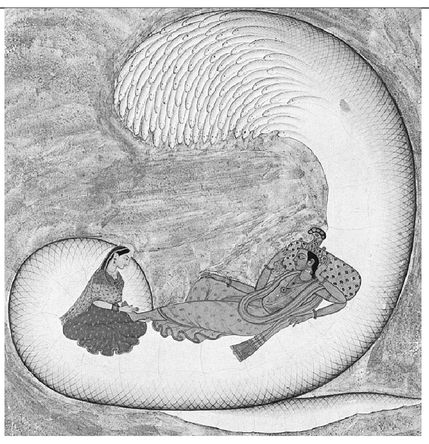

Hindu mythology also provides an example of a serpent of immeasurable proportions, known as Sesha, the thousand-headed serpent that floats on the cosmic ocean while the twin creator beings Vishnu and Lakshmi recline in its coils

.

.

“Vishnu and his wife Lakshmi resting on Sesha, the thousand-headed serpent of eternity, in an interval between the cycles of creation.” From Huxley (1974, pp. 188-189).

Mythological serpents are almost invariably associated with water.

4

In the following drawing based on descriptions by ayahuasquero Laureano Ancon, the anaconda RonÃn surrounds the entire earth, conceived as a “disc that swims in great waters”; RonÃn itself is “half-submerged”âthe anaconda being an aquatic species (

see top figure page 87

).

4

In the following drawing based on descriptions by ayahuasquero Laureano Ancon, the anaconda RonÃn surrounds the entire earth, conceived as a “disc that swims in great waters”; RonÃn itself is “half-submerged”âthe anaconda being an aquatic species (

see top figure page 87

).

The cosmic serpent varies in size and nature. It can be small or large, single or double, and sometimes both at the same time (

see bottom figure page 87

)

.

This picture was drawn by Luis Tangoa, who lives in the same village as Laureano Ancon. These two shamans would have had all the time in the world to reach an agreement about the appearance of the cosmic anaconda. Yet the former draws it as a single sperm

and

a two-headed snake, while the latter describes it as an anaconda of “normal” appearance that completely encircles the earth.

see bottom figure page 87

)

.

This picture was drawn by Luis Tangoa, who lives in the same village as Laureano Ancon. These two shamans would have had all the time in the world to reach an agreement about the appearance of the cosmic anaconda. Yet the former draws it as a single sperm

and

a two-headed snake, while the latter describes it as an anaconda of “normal” appearance that completely encircles the earth.

As the creator of life, the cosmic serpent is a master of metamorphosis. In the myths of the world where it plays a central part, it creates by transforming itself; it changes while remaining the same. So it is understandable that it should be represented differently at the same time.

Â

I WENT ON TO LOOK for the connection between the cosmic serpentâthe master of transformation of serpentine form that lives in water and can be both extremely long and small, single and doubleâand DNA. I found that DNA corresponds exactly to this description.

If one stretches out the DNA contained in the nucleus of a human cell, one obtains a two-yard-long thread that is only ten atoms wide. This thread is a billion times longer than its own width. Relatively speaking, it is as if your little finger stretched from Paris to Los Angeles.

“Cosmovision.” From Gebhart-Sayer (1987, p. 26).

“Aspects of RonÃn.” From Gebhart-Sayer (1987, p. 34).

A thread of DNA is much smaller than the visible light humans perceive. Even the most powerful optical microscopes cannot reveal it, because DNA is approximately 120 times narrower than the smallest wavelength of visible light.

5

5

The nucleus of a cell is equivalent in volume to 2-millionths of a pinhead. The two-yard thread of DNA packs into this minute volume by coiling up endlessly on itself, thereby reconciling

extreme length

and

infinitesimal smallness,

like mythical serpents.

extreme length

and

infinitesimal smallness,

like mythical serpents.

The average human being is made up of 100 thousand billion cells, according to some estimates. This means that there are approximately 125 billion miles of DNA in a human bodyâcorresponding to 70 round-trips between Saturn and the Sun. You could travel your entire life in a Boeing 747 flying at top speed and you would not even cover one hundredth of this distance. Your personal DNA is long enough to wrap around the earth 5 million times.

6

6

All the cells in the world contain DNAâbe they animal, vegetal, or bacterialâand they are all filled with salt

water,

in which the concentration of salt is similar to that of the worldwide ocean. We cry and sweat what is essentially seawater. DNA bathes in water, which in turn plays a crucial role in establishing the double helix's shape. As DNA's four bases (adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine) are insoluble in water, they tuck themselves into the center of the molecule where they associate in pairs to form the rungs of the ladder; then they twist up into a spiraled stack to avoid contact with the surrounding water molecules. DNA's twisted ladder shape is a direct consequence of the cell's watery environment.

7

DNA goes together with water, just like mythical serpents do.

water,

in which the concentration of salt is similar to that of the worldwide ocean. We cry and sweat what is essentially seawater. DNA bathes in water, which in turn plays a crucial role in establishing the double helix's shape. As DNA's four bases (adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine) are insoluble in water, they tuck themselves into the center of the molecule where they associate in pairs to form the rungs of the ladder; then they twist up into a spiraled stack to avoid contact with the surrounding water molecules. DNA's twisted ladder shape is a direct consequence of the cell's watery environment.

7

DNA goes together with water, just like mythical serpents do.

The DNA molecule is a

single

long chain made up of

two

interwoven ribbons that are connected by the four bases. These bases can only match up in specific pairsâA with T, G with C. Any other pairing of the bases is impossible, because of the arrangement of their individual atoms: A can bond only with T, G only with C. This means that one of the two ribbons is the back-to-front duplicate of the other and that the genetic text is

double:

It contains a main text on one of the ribbons, which is read in a precise direction by the transcription enzymes, and a backup text, which is inverted and most often not read.

single

long chain made up of

two

interwoven ribbons that are connected by the four bases. These bases can only match up in specific pairsâA with T, G with C. Any other pairing of the bases is impossible, because of the arrangement of their individual atoms: A can bond only with T, G only with C. This means that one of the two ribbons is the back-to-front duplicate of the other and that the genetic text is

double:

It contains a main text on one of the ribbons, which is read in a precise direction by the transcription enzymes, and a backup text, which is inverted and most often not read.

From Watson (1968, p. 165).

The second ribbon plays two essential roles. It allows the repair enzymes to reconstruct the main text in case of damage and, above all, it provides the mechanism for the duplication of the genetic message. It suffices to open the double helix as one might unzip a zipper, in order to obtain two separate and complementary ribbons that can then be rebuilt into double ribbons by the duplication enzymes. As the latter can place only an A opposite a T, and vice versa, and a G opposite a C, and vice versa, this leads to the formation of two

twin

double helixes, which are identical in every respect to the original. Twins are therefore central to life, just as ancient myths indicate, and they are associated with a serpentine form.

twin

double helixes, which are identical in every respect to the original. Twins are therefore central to life, just as ancient myths indicate, and they are associated with a serpentine form.

Without this copying mechanism, a cell would never be able to duplicate itself, and life would not exist.

DNA is the informational molecule of life, and its very essence consists in being

both single and double,

like the mythical serpents.

both single and double,

like the mythical serpents.

Â

DNA AND ITS DUPLICATION MECHANISMS are the same for all living creatures. The only thing that changes from one species to another is the order of the letters. This constancy goes back to the very origins of life on earth. According to biologist Robert Pollack: “The planet's surface has changed many times over, but DNA and the cellular machinery for its replication have remained constant. Schrödinger's âaperiodic crystal' understated DNA's stability: no stone, no mountain, no ocean, not even the sky above us, have been stable and constant for this long; nothing inanimate, no matter how complicated, has survived unchanged for a fraction of the time that DNA and its machinery of replication have coexisted.”

8

8

At the beginning of its existence, some 4.5 billion years ago, planet earth was an inhospitable place for life. As a molten lava fireball, its surface was radioactive; its water was so hot it existed only in the form of incondensable vapor, and its atmosphere, devoid of any breathable oxygen, contained poisonous gases such as cyanide and formaldehyde.

Approximately 3.9 billion years ago, the earth's surface cooled sufficiently to form a thin crust on top of the molten magma. Strangely, life, and thus DNA, appeared relatively quickly thereafter. Scientists have found traces of biological activity in sedimentary rocks that are 3.85 billion years old, and fossil hunters have found actual bacterial fossils that are 3.5 billion years old.

During the first 2 billion years of life on earth, the planet was inhabited only by anaerobic bacteria, for which oxygen is a poison. These bacteria lived in water, and some of them learned to use the hydrogen contained in the H

2

O molecule while expelling the oxygen. This opened up new and more efficient metabolic pathways. The gradual enrichment of the atmosphere with oxygen allowed the appearance of a new kind of cell, capable of using oxygen and equipped with a nucleus for packing together its DNA. These nucleated cells are at least thirty times more voluminous than bacterial cells. According to biologists Lynn Margulis and Dorion Sagan: “The biological transition between bacteria and nucleated cells ... is so sudden it cannot effectively be explained by gradual changes over time.”

2

O molecule while expelling the oxygen. This opened up new and more efficient metabolic pathways. The gradual enrichment of the atmosphere with oxygen allowed the appearance of a new kind of cell, capable of using oxygen and equipped with a nucleus for packing together its DNA. These nucleated cells are at least thirty times more voluminous than bacterial cells. According to biologists Lynn Margulis and Dorion Sagan: “The biological transition between bacteria and nucleated cells ... is so sudden it cannot effectively be explained by gradual changes over time.”

From that moment onward, life as we know it took shape. Nucleated cells joined together to form the first multicellular beings, such as algae. The latter also produce oxygen by photosynthesis. Atmospheric oxygen increased to about 21 percent and then stabilized at this level approximately 500 million years agoâthankfully, because if oxygen were a few percent higher, living beings would combust spontaneously. According to Margulis and Sagan, this state of affairs “gives the impression of a conscious decision to maintain balance between danger and opportunity, between risk and benefit.”

9

9

Around 550 million years ago, life exploded into a grand variety of multicellular species, algae and more complex plants and animals, living not only in water, but on land and in the air. Of all the species living at that time, not one has survived to this day. According to certain estimates, almost all of the species that have ever lived on earth have already disappeared, and there are between 3 million and 50 million species living currently.

10

10

DNA is a

master of transformation,

just like mythical serpents. The cell-based life DNA informs made the air we breathe, the landscape we see, and the mind-boggling diversity of living beings of which we are a part. In 4 billion years, it has multiplied itself into an incalculable number of species, while remaining exactly the same.

master of transformation,

just like mythical serpents. The cell-based life DNA informs made the air we breathe, the landscape we see, and the mind-boggling diversity of living beings of which we are a part. In 4 billion years, it has multiplied itself into an incalculable number of species, while remaining exactly the same.

Other books

Take Me I'm Yours (Coffee House Chronicles) by Miles, Michelle

Black Swan Rising by Carroll, Lee

Suzy's Case: A Novel by Siegel, Andy

Wives at War by Jessica Stirling

The Language of Souls by Goldfinch, Lena

At the Mercy of the Queen: A Novel of Anne Boleyn by Anne Clinard Barnhill

Linc's Retribution by Lake, Brair

Poison Shy by Stacey Madden

For All to See (Bureau Series Book 1) by Megan Mitcham

The Anatomy of Violence by Adrian Raine