The Correspondence Artist (10 page)

Read The Correspondence Artist Online

Authors: Barbara Browning

Â

Plot â comes from the Middle English, and the first meaning is a parcelle de terrain, a plot of land. Then a map of that terrain. And from map comes the plan or outline of a story. But it's also a verb meaning to connive. It has nefarious connotations. You plot to kill the king.

Â

You see? You preferred my first manuscript, which was a roman sans intrigue. Moi aussi, je préfère les romans sans intrigue. I always said I couldn't write anything with a plot. Only poems, or essays. But after I wrote a novel without a plot, everyone (everyone but you) said “where's the plot?” So I tried to write a novel with a plot. And everyone else said, “I like the plot but what's with all those long weird digressions?” And you said, “I like the long weird digressions but I have a problem with the fictional part.” You're so strange. I love the way you read me.

Â

I think we'll never agree about racial representations. In this respect, I'm American. It's generational, too. I know that. I also know my country is full of hypocrisy about these things. I see that. Still, I found some of the images in your new series very objectifying. Of course that happens here all the time, but in advertising. The exploitation is explicit. And I still find it strange when you refer to your “petite africaine.” I realize nobody escapes ethnic eroticism. We already had that long exchange. Hiroshima, mon amour. All of that. But it's complicated. And Americans will always hear it differently.

Â

All my pictures of flowers come from my little digital camera, but the bonobos came from Google. If you type “bonobo sex” in Google images you will be surprised what pops up. And though I've tried my best not to be vulgar, I'm sending

you a SHOCKING image of une femelle à se masturber. Because I thought she was beautiful.

you a SHOCKING image of une femelle à se masturber. Because I thought she was beautiful.

Â

Please excuse me if you find this message enervating. I told you once, even when I disagree with you, I find you fascinating, and very moving.

Â

I send you a kiss.

Â

Â

You see how things run together in our correspondence. I was talking about the etymology of “plot” and suddenly we were in the terrain of race and eroticism. But of course we were also already in the terrain of romance and intrigue, so maybe it's not such a leap. The part about the bonobos I'll explain later.

The long and the short of it is: Binh has a strange and wonderful sensibility which sometimes disturbs me, but always intrigues me. And he seems to feel this way about me. This may explain our repetition compulsion. Which is to say, we often seem to be coming back to the same conversation. I'm talking about me and Binh, but I could of course be talking about Tzipi.

Why do we both persist in having multiple lovers? It's not that we're squeamish about commitment. I told you, the paramour is fundamentally a monogamist. I know I also have that impulse. I think the most plausible explanation is Lacan's. When he's analyzing “The Purloined Letter,” he anticipates the question of why it's the Minister who compulsively repeats the Queen's bad action: “The plurality of subjects, of course, can be no objection for those who are long accustomed to the perspectives summarized by our formula:

the unconscious is the discourse of the Otherâ¦

” I know you may find this unsettling, but the truth is, it doesn't

matter

that it's somebody else. It's

always

somebody else.

the unconscious is the discourse of the Otherâ¦

” I know you may find this unsettling, but the truth is, it doesn't

matter

that it's somebody else. It's

always

somebody else.

I already mentioned that e-mail I wrote with the subject heading “fiction” â the one about “falling in love” and the impossibility of believing in the paramour's singular necessity. I attributed

that to “emotional distance,” and I said that there were all those other kinds of distance between us â of language, nation, age, social context. Fame. But of course later Binh and I got to discussing whether eros even exists without

some

kind of difference â even between lovers of the same sex. The other question is whether eros ever exists without similarity.

that to “emotional distance,” and I said that there were all those other kinds of distance between us â of language, nation, age, social context. Fame. But of course later Binh and I got to discussing whether eros even exists without

some

kind of difference â even between lovers of the same sex. The other question is whether eros ever exists without similarity.

Â

Â

Â

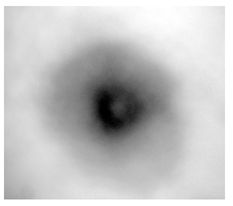

Binh is extremely sensitive to language, but he also has access to this other language â the language of light and color and shape â and often his most poetic messages are videos, or just embedded images â take, for example, this photograph of his nipple, staring back at the camera like a pure, unblinking eye:

I treasure these communications. It's not just that they tend to be so erotically potent. They're often full of wit, or tenderness, or fear, or pain.

But because I tend to write more words, he sometimes expresses a kind of intimidation about our correspondence.

Â

Â

Sunday, April 1, 2007, 1:02 a.m.

Subject: words

Â

“Désembarrassée” is the generous version. Another way of saying I have logorrhea. I write too much. I'm the one who gets completely inarticulate talking to you. Especially after sex, when you suddenly begin to speak with what our friend Holland Cotter referred to as your “almost devastating elegance.”

Â

Speaking of sex, I woke up again wanting you. I touched my whole body and came with two fingers inside myself. It was slippery and muscular and beautiful, and I was imagining what you would be feeling if my fingers were your sex.

Â

Â

I was referring, of course, to that enormous, adoring piece Cotter had written in the

Times

about Binh's Guggenheim show. I agreed with everything he said. I'm often devastated by that elegance. And I often wake up like this, wanting Binh.

Times

about Binh's Guggenheim show. I agreed with everything he said. I'm often devastated by that elegance. And I often wake up like this, wanting Binh.

He liked that paragraph about my fingers. He later told me it made him remember exactly what it felt like when his sex was in mine. He sent me back a .mov file. At first, I was a little confused when I saw it on that little QuickTime viewer. It seemed to be a snail, or a slug â some strange mauve creature, but with a delicate, powdery texture. Whatever it was, it was moving slowly, struggling, lifting its heavy head. Its unhurried, narcotic motion was mesmerizing. There was a kind of halo around it. It shifted, and began to grow. And as it grew, I realized with a smile what it was. It was Binh's unspeakably beautiful, perfect, uncircumcised penis rising up in a graceful erection.

It swayed there on my computer screen, tumescent, magnificent creature, with that strange, golden halo around it. I almost put my mouth on the screen.

Given our age difference, it will not surprise you to learn that one issue that repeatedly comes up in Binh's sessions with his shrink is his relationship with his mother. I told you, the paramour only fell in love once, in childhood. Despite his utter dedication to her, Binh rarely calls his mother on the phone. She's resistant to e-mail, but even if she weren't, I'm not sure Binh would write her. She, like me, has also complained of his lack of demonstrativeness. Some art critic once did a story on Binh's early life in Hanoi, and when he interviewed his mother, she smiled and shook her head, saying, “Binh was always very distant.” She adores him as much as he her, but they both seem to acknowledge the necessity of the distance, both geographical and psychological, that Binh has had to place between them.

I still haven't met her. And since things seem to be petering out, I guess maybe I never will. It would be awkward, anyway. She's still having a hard time getting over the fact that Binh separated from Aafke. She thinks a man's place is with his family. Binh's father died years ago, but when he was alive, he was a very good husband. Binh says his parents were in love until the day his father died. He really thought he'd be with Aafke to the end as well. But it wouldn't take a psychoanalyst to figure out that they didn't begin under the most auspicious of circumstances. They were both just kids. It all happened so fast.

When Binh was seventeen, he was one of five students selected from the Hanoi University of Fine Arts to travel to Paris 8 under the auspices of an exchange sponsored by the French government. Three of the others were painters. One was a sculptor. Binh was the only “conceptual” artist of the bunch. He was also the youngest, the smartest, the most freakishly gifted, and the most promiscuous. In Paris, he was like a kid in a candy store. He went to underground performance art events in the scuzziest warehouses of the

banlieue

. He went to smoky experimental video screenings in the swank apartments of art school

ingénues

. He made out with boys and girls. Everybody wanted

him. It wasn't just his physical beauty â they could sense already his brilliance. It was that “old soul” thing. Binh is very special.

banlieue

. He went to smoky experimental video screenings in the swank apartments of art school

ingénues

. He made out with boys and girls. Everybody wanted

him. It wasn't just his physical beauty â they could sense already his brilliance. It was that “old soul” thing. Binh is very special.

He met Aafke in a café where she was waiting tables â a luminous Dutch girl with cornflower blue eyes and hair the color of butter. He told her it was funny to find himself with a Dutch girl because when he was a kid he used to joke that he was a Swede. He meant, of course, that his political impulses put him out of sync with most Vietnamese. He had a particular abhorrence of anything that whiffed of sexism. From a very tender age, Binh declared himself a feminist.

When they first started going out, Binh told me, Aafke had seemed to correspond to his sexual open-mindedness. She had adventures of her own. Sometimes they had them together. Binh said, “In the beginning, she was so EU.” Everybody was invited. But when they decided to get married she started to get more territorial â especially after she became pregnant with Bao and Bob. Twins. I've seen them several times when they've come to stay with Binh. He's an extremely dedicated father. You can't imagine how beautiful they are: glowing copper-colored skin, copper-colored hair, copper eyes. It's as though Binh had spent hours enhancing their digital tone, hue, and saturation on his computer.

Aafke had to deliver them by C-section. I'm sure if they had been born in the US the hospital wouldn't have allowed this, but Binh made a digital video of their birth. He showed me some of the images: close-ups of Aafke's incredibly pale face, the thin blue veins visible under her closed eyelids; the saturated red of her blood as the knife sliced into her abdomen; the two gelatinous, gory, squirming boys wriggling out of the slit. I found the video extremely beautiful, but I understood why even Binh found this material too intimate to use in a public art project. This made me feel a little bit better about the fact that he'd never actually used any images of me, outside of our private correspondence. He didn't seem to mind using images of his other

lovers, like that big, pretty Ethiopian girl, or that break-dancer named Jean-Philippe.

lovers, like that big, pretty Ethiopian girl, or that break-dancer named Jean-Philippe.

Shortly after the twins were born, Binh and Aafke decided to move to Berlin because it was cheaper, and because the experimental art scene struck Binh as more vital. He hooked up with Lars and some other crackpots, Aafke got increasingly pissed off, he couldn't take it anymore, they separated, there was the YouTube thing⦠and the rest is history.

Â

Â

Saturday, June 9, 2007, 4:08 p.m.

Subject: Darwin

Â

You think you're different (Swedish Vietnamese, homo/heterosexual, right wing leftist, Darwinist feministâ¦). I also think I'm pretty unusual. Maybe it's a lot of egotism on both our parts. But of course I agree that we are (we should all be) experimental.

Â

Â

Maybe you'll think it's just laziness on my part if I say of some of our differences, “They're generational.” Maybe I ought to push him harder on some of these things. Binh may really be a hypocrite. He's certainly been accused of that. His politics are weird. He's constantly assuming the underdog position. He claims, for example, to be fundamentally gay, even though the vast preponderance of his sexual activity is with women. He told me that André Gide liked to say that he was a “

lesbien

,” as opposed to a

lesbienne

. I can't even begin to go into the Darwin business right now. Suffice it to say that his feminism might, on occasion, come into question.

lesbien

,” as opposed to a

lesbienne

. I can't even begin to go into the Darwin business right now. Suffice it to say that his feminism might, on occasion, come into question.

Other books

Thank Heaven Fasting by E. M. Delafield

Angels of War (Angels of War Trilogy Book 1) by Andre Roberts

The Eighth Day by Salerni, Dianne K.

Vampires and Sexy Romance by Eva Sloan, Ella Stone, Mercy Walker

Fethering 08 (2007) - Death under the Dryer by Simon Brett, Prefers to remain anonymous

Grin by Keane, Stuart

With a Little Luck by Janet Dailey

Once A Warrior (Mustafa And Adem) by Anthony Neil Smith

Texas Strong by Jean Brashear