The Copa (17 page)

Authors: Mickey Podell-Raber

My daughter, Jama, performing on stage at the Copa with a friend.

In 1972 Jules made another radical change; he decided to close the Copa for the first time in decades during the summer months. With many New Yorkers leaving the city for vacations at that time, it seemed like a wise decision economically. The Copacabana was not the only club suffering from a decline in business. In fact, many nightclubs had already closed their doors or would in the next few years. The new generation was content to go to a club and dance to a disc jockey spinning records as entertainment. The future was bleak and this distressed my father. The main source of happiness in his last years seemed to be derived from Jama, his first granddaughter.

Jama recalls:

I have amazing memories of my grandfather. While others may have feared him or thought of him as gruff and abrasive, he was a gentle giant to me. Everyone seemed to walk on eggshells around him, but I never felt scared of him. The only time he was a little too rough was when we would have our picture taken at the Copa and he would practically choke me as he was hugging me. I would play dominoes with him when he was home and he'd let me take his order on the Copa pads, the ones the waitresses would actually use at the club, for his lunch. When we moved to Lancaster [Pennsylvania] we got a cat; it was a white Persian cat named Hector. My grandfather was not much of a pet person, but

when we would visit him in New York we would bring the cat along. Needless to say, Hector was supposed to be kept away from my grandfather at all times. You can imagine the tension one day when we were all sitting in his office and the cat jumped up on his desk. Everyone in the room froze but me, waiting for my grandfather's reaction. I'll never forget the way Mother glared at me. Because it was my cat, my grandfather didn't say or do anything and the cat was quietly removed without a scene. When it came to his rules, I had special privileges.

My father and a group of friends.

My second child, another daughter, Danielle, was born in 1972. I was actively involved with my children and tried to be a hands-on mom to them. Of course my mother thought I was crazy and would say so. She was shocked that my children were going to public schools. “I am leaving you money, and I want you to get a governess for your children. You don't know how to be a parent.” I replied, “And you did?” I told her she wasn't there for me emotionally and that nurses practically raised me. “I went to your school plays, didn't I?” was her retort. She was shallow in that regard; she really didn't know better. The fact that she was so wrapped up in being Mrs. Jules Podell left little time for her to devote to me. She loved the fame; she'd walk in a room and everyone would dote on her.

By 1973 rumors circulated that my father might close or sell the Copacabana. Longtime friend and syndicated columnist Earl Wilson asked him if the rumors were true. My father replied, “I haven't sold out, everything is the same as it was, and, as I told you, I'm going to open in the fall. I don't pay attention to rumors, and don't you.”

The tough facade he had built and polished over the decades, which served his position, reputation, and status, would soon begin to disintegrate. In the past, that facade vanished only for a few hours at a

time, when he would lavish gifts on the orphans during the holidays at home or the club. Now it was slipping away as those he knew and worked with over the years themselves were either dead or retired and the club was on its last legs. His partner for decades, Jack Entratter, would hang on at the Sands in Las Vegas until he passed away from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1971. Entratter's status and position at the hotel had also diminished after the powers that be sold the hotel to billionaire Howard Hughes in 1967.

Even though things were tough for the club, my father was constantly trying to think of ways to keep it open and successful. It was hard for him to come to the realization that he hadn't anticipated when it was time to get out of the business and retire. It probably would not have mattered if he had, for the Copa was his life. My father had no hobbies; he had nothing besides the Copa. Nothing. So as the Copacabana began its decline and started to die, so did he. On September 27, 1973, my father passed away. The heart and soul of the Copacabana also died that day.

The day my father died was Rosh Hashanah. In the past, he'd never gone to temple on this holiday; he went only on Yom Kippur. Well, this day, for some reason he decided to go. Apparently, my father woke up and told Jackson to get the car ready, as he wanted to go to temple. My mother called me and said, “I don't know what is going on, but your father wants to go to temple today.” So he went, and then he came back and they were sitting in the den and he said, “Claudia, I love you,” then suddenly suffered a fatal heart attack. This was my mother's version of what happened.

Whether she was accurate or not didn't matter; I was thankful that he passed away peacefully; it was quick and seemingly painless. It

seems he knew his time was coming and went without a struggle; he simple lost his will to live. His decision to attend Rosh Hashanah services that afternoon makes me think he had some premonition of his end.

It was ironic that hardly any celebrities attended his funeral; some sent telegrams, but that was it. There were photographers outside the funeral home, but it was really sad and amazing that with all of the people he had given a break to and set up, none came to pay their respects.

My mother did not last long after my father's death. He was the focus of her life, and when she lost him a big part of her was gone. Their life was a very strange love story. They loved each other in their own way. She was gorgeous; it was like Beauty and the Beast. I guess they were meant to be with each other. I still remember how she would sit there at lunch and would make sure that his food was the way he liked it. She'd just sit with him while he ate and then off he would go to the club.

My mother eventually moved to the Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach, Florida, where she enjoyed being treated as a queen until her passing in 1976, shortly after my son, Benjamin, was born.

It wasn't until after my parents had passed that I decided to try to track down information on my birth parents. I'm not sure why I waited so long; maybe I thought it might hurt Jules and Claudia. I was also busy living my life and having children.

As I was going through some family belongings, I came across my birth certificate at the very bottom of a box of pictures. I'll never forget that day; I was in my garage and I saw this birth certificate for a baby girl born on February 11, 1945, at Sydenham Hospital, New York. My birth mother's name was Frances Goldberg and my birth name was

Linda Goldberg. The paper stated that Jules and Claudia Podell had adopted me.

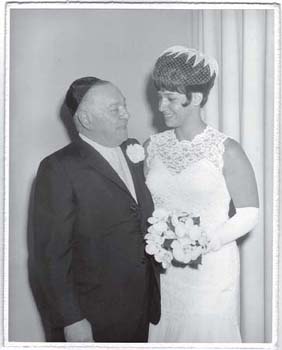

My father and me before giving me away at my wedding.

By the time I came across this information, my birth mother was dead. I would later find out that I had three siblings, a half sister, and two half brothers. After making contact with them, they informed me that we had a surviving aunt living in the projects in Brooklyn. My half sister took me to see my mother's sister Martha. The entire experience was surreal. Here I was in Brooklyn, talking to this woman lying in a bed who told me she had been with my birth mother the night I was born. Prior to that, my mother had been put up in a hotel and was taken to the hospital once she went into labor. All Martha recalled was that once I was born, my mother signed adoption papers and I was taken away.

I was still curious about how Jules and Claudia had made a connection with my mother. From what Martha told me, it seems that her sister must have known someone who knew my father or was possibly associated with the club. That “missing link” put them together to set up the adoption transaction to occur. I say “transaction” because my father paid Frances Goldberg, in addition to taking care of her hotel and hospital expenses. Since everyone involved at the time of the adoption is dead except me, the specific facts will forever remain a mystery.

Needless to say, my siblings did not grow up in the luxurious surroundings that I was afforded as the adopted daughter of Jules and Claudia Podell.

Time marches on, and while I do miss my parents and the excitement of the Copacabana, I lead a very satisfying life. Today I'm married to a wonderful man, and I have three wonderful children and I am a proud grandmother.

After my father passed away, the Copa would remain shuttered for several years. Rumors would circulate and items would appear in the press about the future of the club every few months.

In a 1975 interview, Frank Sinatra summed up his feelings regarding the nightclub era: “I do know that when the Copacabana closed, it was the end of a great era, of the so-called cabaret era, where all the names in show business worked. Everybody worked there; it was a great age at the time. There are no rooms in New York like that nowâ¦and there's no reason why there isn't a club like that in New York City today because every performer who works in Las Vegas would like to work New York at least three times a year. So figure how many people there are who would workâit would be loaded all the time.”

While Sinatra could have easily filled such a club three or more times a year, most acts were not popular enough to do so. Also, because of the gaming revenue generated in Las Vegas, the show rooms were able to pay the entertainers a large fee in order to draw gamblers to their hotel casinos. Such was not the case in New York and clubs were unable to compete with the salaries offered elsewhere.

It was not until 1976 that the Copacabana finally reopened; this time it would be operated as both a disco and cabaret. The New York press praised the new owners and their renovation of the club and predicted that the new venture would be a success.

After a few years, the new owners of the Copa moved the location to 617 West Fifty-seventh Street. The club now catered to a Latino market. The Copa would again move, this time to 560 West Thirty-fourth Street, which had a larger dance floor and a more modern sound system. The weekly entertainment schedule consists of Latin salsa-style music and dance. Some remnants of the old Copa, such as the palm

trees and tropical theme, remain. The club also does a brisk business as a catering hall for wedding and banquets.

In 1978 Barry Manilow would turn the Copacabana into a household name again with his hit song of that name. For the past three generations, the strongest link to the Copacabana's glorious past is that song.

Manilow recalled:

I went to the Copa for my prom in the 1960s; I think I saw Bobby Darin. I remember lots of palm trees and the beautiful waitresses there. For a young man, the Copa was all very adult. I never met Jules Podell. The Copacabana symbolized glamour and danger to me. The song was born when Bruce Sussman and I were on vacation in Rio and we were staying at the Copacabana Hotel. There were towels with

Copacabana

sewn into them all over the place, matchbooks with

Copacabana

engraved on them, signs with

Copacabana

blazing on them, and we were getting sun on the Copacabana beach when Bruce sat up and said, “Barry, has there ever been a song called âCopacabana'?” I said I didn't think so. When we got back to the states, Bruce called me from his place in New York to my place in Los Angeles and asked me about that idea for a song called “Copacabana.” I told him that I thought that he and his collaborator, Jack Feldman, should write me a lyric that would be a story song à la Frankie and Johnny; a story about a love triangle with a death in it; something you would see on television at 2

A.M.

They called me back in an hour and read me the brilliant lyric to “Copacabana.” I set music to it within a half hour and the song “Copacabana” was born. An interesting story: years later, I was walking down Sixty-first Street and saw workmen tearing down the outside of a building. As I got closer, I realized that they were tearing down the old Copacabana nightclub. I went inside and stood in the middle of the dust and

beams; it was indeed the Copa where I had spent my prom night. I spoke with some of the workmen who recognized me. They told me that they were moving the Copa to Fifty-seventh Street. New Yorkers and I are family, and before I left, one of them folded up the Copacabana awning and gave it to me. I was so moved. I still have it among my valuable collection of memorabilia.