The Convert: A Tale of Exile and Extremism (19 page)

Read The Convert: A Tale of Exile and Extremism Online

Authors: Deborah Baker

Pathans rarely married outside their clan; Khan’s father had arranged the match with Shafiqa, his cousin. As if to replace the sense of family and cohesion he had lost in the migration to Pakistan, Khan was intent on having as many children as possible. Shafiqa had borne him five, one for each year of their marriage. Four survived. Khan’s regard for Mawdudi was such that he hoped to have at least as many children as he had and had even taken to naming his sons and daughters after the Mawlana’s. In her first letter describing Khan’s home, Maryam had marveled at the infectious energy of the women, contrasting it with the sickly lassitude of their babies. It was as if Mohammad Yusuf Khan was intent on challenging Allah to provide for them, no matter how many babies arrived or how precarious their existence.

c/o Mohammad Yusuf Khan

15/49 Sant Nagar

Lahore

PAKISTAN

Mid-August 1963

On the afternoon of my visit to the Mawdudi home, I took pains to be quiet and well mannered, chastened by the chance to make amends with Begum Mawdudi and her children. The visit went so smoothly that I was invited to stay for dinner. At the dinner table, however, as soon as I opened my mouth the Mawlana began immediately to scold me, launching into his familiar tirade. He complained of my tiresome talk. How he had to commit me to the madhouse, and how when I received Mother’s letter I had thrown such a hysterical fit that even the American consul was all for putting me on the first plane home. When he looked at me with the cold fury I knew all too well, I realized I was no longer quite as frightened of him as I once had been.

I have never known a person like you, so completely sane in your writings but then to see you…

I interrupted. Mohammad Yusuf Khan has asked to marry me. Please tell me what you think I should do.

The Mawlana looked silently at his plate, his head sunk into his shoulders and his beard draping his chest like a napkin. He frowned. I waited.

Given that you are as you are, I hesitate to take the responsibility of recommending you to anybody. And if after marriage you do not improve, then what? Here is a man of the very best character who is willing to carry the burden. He looked at me with fury and exasperation. Why do you then refuse him?

He paused and looked around the table, suddenly aware of his children’s astonished stares. Sixteen-year-old Haider, eighteen-year-old Husain, and eleven-year-old Khalid were completely engrossed.

Anyhow, you should have spoken to me about this only in private. This is not the place or the time to discuss such matters. Mawdudi looked at his children’s expectant faces.

Perhaps the children didn’t understand me, he added hopefully. They hardly know English.

The table erupted.

Mother, I can only guess at your surprise when you received word of my marriage. Do you remember how often you would complain that if I didn’t go out on dates with boys, I would never gain any experience? How you had despaired at my marriage prospects. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to get married. I just could never figure out how to draw the line. I sacrificed a “mixed” social life to maintain my virtue.

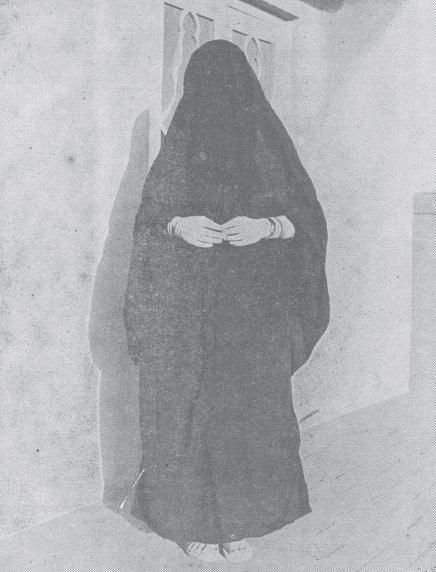

But I am now home with my Khan Sahib, my co-wife Shafiqa, her children and aging mother, and many other relations. Only horse-driven tongas, donkey carts, and the occasional water buffalo find it possible to navigate the streets of our little neighborhood in a rundown part of Lahore. In my chair by the window in my room I can watch the life on the street passing by, secure in the knowledge that while I might know the face of every beggar, street vendor, and child who passes beneath my window, I am myself unseen. After a long search, I have found my place and I will never exchange it for any other. You no longer have to worry about me. I believe I am going to be very happy now.

Inshallah.

If you go outside your self

You will be under the veil of unity.

And if you go beyond the why and the when

You will leave your self

For the without of why and when

Mas’ud-e-Bakk

CHAPTER 7

The Renegade

In December 2007 I arrived in Pakistan to find Lahore aflutter with demonstrations against the government. In an effort to keep his hold on power, General Pervez Musharraf, the most recent of Pakistan’s unelected military leaders, had fired the Supreme Court’s chief justice the previous March, setting the entire legal community against him. The prospect of the coming elections and the recent return from exile of Pakistan’s former prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, added to the air of possibility, uncertainty, and unrest. Massive cheering crowds had met her plane’s arrival on October 18. Yet as her motorcade left the airport, two explosions set off by suicide bombers killed 136 of her followers, including 50 members of the private security detail ringing her vehicle. Hundreds more were injured. Bhutto survived unscathed but shaken.

From that moment, the hope for a peaceful return to democratic rule, along with whatever power-sharing arrangement Bhutto had made with General Musharraf, began to unravel. On November 3, the general had declared a state of emergency, suspending the constitution. Though he cited the rise of religious extremism as part of his rationale for the imposition of emergency rule, he also released from prison a number of Taliban insurgents. This raised the question of who was calling the shots, the military or those in the ranks of Pakistan’s secret service, the ISI, whose agents were known to have ties with al-Qaeda and the Taliban. Bhutto named four individuals in the ISI who she believed had orchestrated the attempt to assassinate her. A week before my arrival, she filed her nomination papers for the January parliamentary elections, escalating tensions still further.

Despite widespread arrests and accounts of police brutality, public opposition to the firing of the chief justice was courageous and unflagging, more exuberant than angry. The city’s lawyers suspended court appearances and organized peaceful street protests. Joined by students and activists, the Lahore crowds numbered about a thousand. This comprised the city’s sum total of what the newspapers referred to as “civil society.” Nonetheless, the Lahore lawyers, distinct and elegant in their black suits and white shirts, seemed to be everywhere, weaving their way through crowded sidewalks and traffic-stalled streets like clerics in a holy city.

In their call for an independent judiciary and an end to military rule, the Lahore lawyers were supported by the Jamaat-e-Islami. No one seemed to note or remark upon the oddness of this alliance. Musharraf suppressed the Jamaat-e-Islami along with every other opposition party, just as General Ayub Khan had once done. The Jamaatis found themselves in the same cells as members of the secularly inclined civil society, represented by the same lawyers. Yet if they acknowledged each other at all, it was with deep distrust.

I stayed in a private home in the gated and heavily guarded suburb of Gulberg. Gulberg figured in Maryam’s letters as the “Park Avenue” of Lahore. My hosts were among the most powerful voices of the independent media, which had also been subject to Musharraf’s crackdown. Occasionally BB, as Benazir Bhutto was familiarly known, would call to solicit advice about putting together a government and trade gossip about her political opponents.

My hosts kept Bhutto at arm’s length, focused more on the lawyers’ protests than on the coming election. In the afternoons, they hosted strategy sessions over tea and cake. One woman sighed resignedly when she mentioned that friends from London had canceled their holiday plans to visit. A recent

Newsweek

cover story had described Pakistan as the most dangerous nation in the world. “Of course it’s perfectly safe,” she added quickly, putting down her cup of tea. “It is just hard to explain that to Westerners.” In the evenings we rode in chauffeured cars, accompanied by a guard and his Kalashnikov.

Though I had spent twenty years traveling between India and America, it was my first visit to Pakistan. Instead of the two-week tourist visa I had requested, I was given a five-year multiple entry visa for “family visit,” which happened to match the visa I had for India. When I questioned this, the consular official waved me off with a smile. Similarly, the officer at the Lahore airport immigration desk had tapped the little round camera taking my photograph and said, ruefully, “a gift from America.” There were many such reminders of the special relationship between America and Pakistan. Indian officials I found rather more… officious.

One evening I accompanied my hosts to a wedding reception. The event took place in a fancy hotel owned by the bride’s father. We arrived after 1:00 a.m.; people were still waiting for the food to be served. Behind a beaded curtain a belly dancer snaked and swayed on a tiny elevated stage while guests milled around. The women were festively dressed and generously accessorized. It wasn’t that much different from a fancy Delhi wedding reception, though there it would be Bollywood dancing, and the wedding party might well join in.

A few of the wedding guests were recently released from house arrest; many had marched with the lawyers. One businesswoman indicated that one of the reasons she marched was just this, raising her cigarette and drink. I looked around: only the belly dancer wore a headscarf. Was this what a secular rule of law amounted to? Cigarettes, illicit alcohol, and dancing girls? No wonder the ranks of civil society were so thin and in need of hired guns. Such a limited notion of individual freedom would mean little to those who had difficulty putting food on the table. I recalled Mawdudi’s warning to the students at Lahore Law School almost exactly sixty years before: Pakistan’s secular and Westernized elite would hijack Pakistan for their own ends.

Not all had. A few days later a legendary civil rights lawyer visited the house in Gulberg. For years her life had been a succession of death threats, jail terms, and beatings. Her manner bore the scars of her vigilance on behalf of values that might be better described as humanist than exclusively Western or secular. In her law practice she defended the least powerful from the clear-cut and unjust incursions of Sharia laws upon secular ones—a blind rape victim accused of fornication, a Christian boy accused of blasphemy—but tyranny in all its forms haunted her. That day, recently released from house arrest, she had stormed the gates of the shuttered courthouse, a flock of lawyers behind her, pulling at the chains as if her tiny arms might break them.

It was this woman who provided me the telephone number of Haider Farooq Mawdudi: Haider Farooq, who, alone of Mawdudi’s nine children, had befriended Maryam on her arrival in Pakistan. In civil society circles he was regularly referred to as a “renegade.”

I didn’t think to ask what they meant by that.

I first began to suspect that Maryam Jameelah had lived to see the September 11 attacks when I came upon the illustrations for

Ahmad Khalil: A Biography of a Palestinian Refugee

in her archive. Maryam Jameelah described

Ahmad Khalil

as a novel she began at the age of fifteen and worked on for ten years. It was part of her efforts to counter Zionist propagandist fiction like Leon Uris’s blockbuster melodrama

Exodus

and Arthur Koestler’s

Thieves in the Night.

If the British raj was Mawdudi’s bête noire, from 1949 onward the Zionists were Maryam’s. Quoting Theodor Herzl’s diaries, Maryam had noted the parallels between Herzl’s stated Zionist mission and European imperialism in Asia and Africa: “We should in Palestine form a portion of the rampart of Europe against Asia,” Herzl wrote, “an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism.”

Yet in the copy of the novel she left behind in the library, Maryam struck a far more humble note. The first draft and initial illustrations for the book, she wrote, were finished when she was trying to find her way out of a nervous breakdown and the dark years of hospitalization that followed. As much as she aspired to write a work of literature, Maryam reluctantly admitted that the book was fatally encumbered by her agenda. Yet of all the books she would write,

Ahmad Khalil

remained her favorite.

Ahmad Khalil is a peasant whose Job-like life embodies the suffering and nobility of the Palestinian fellaheen. For his ancestral village Margaret chose the real settlement of Iraq al-Manshiya, a village on the eastern edge of the Gaza Strip. Within days of signing an armistice agreement, with Egypt guaranteeing villagers the right to remain in their homes, in March 1949, the local Israeli garrison, acting under orders of “intimidation without end,” drove its Arab residents from the land.

Margaret turned fifteen two months later. In the novel she began that year, Ahmad Khalil would kill five Israelis during the siege of his village before being arrested. His prison guard, still bearing the tattoo that marked him as a recent survivor of a Polish concentration camp, becomes his tormentor. It was hard not to see in this turn of events the specter of Dr. Cohen, Margaret’s psychiatrist at Hudson River State Hospital. The first draft of

Ahmad Khalil

was completed there.

In the course of the novel Khalil endures every indignity, every possible twist of misfortune. As a child he witnesses the death of his mother at the hands of Israeli soldiers. As an old man, living in exile in Mecca, he sees his own son lose his faith and, after oil is discovered on the Arabian Peninsula, embrace the mantra of Westernized progress. Yet Khalil learns to accept his fate with stoic resignation to the will of Allah. “Every minute of our lives we are being tested,” Maryam writes elsewhere, “and the suffering and misfortune we endure on this earth is not the decisive calamity but only part of the testing.” The story of Ahmad Khalil was clearly Margaret’s and Maryam’s, one she would spend her whole life writing and revising, drawing and redrawing, even after the novel was finally published in Lahore.

Maryam Jameelah’s archive contains three boxes of drawings and paintings. The first box contains the disassembled portfolio she had left with Mr. Parr as she prepared to depart for Pakistan. Her cover note cites the Egyptian hieroglyphs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Diego Rivera’s murals, and the drawings of Käthe Kollwitz among the influences on her art. The paintings, done in vivid pastels, consist largely of portraits and scenes from village life in Palestine. There are portraits of men in brightly striped jellabiya reading Arabic newspapers. There are weavers, boys learning the Qur’an, fathers bathing their children, mothers tenderly trying to nurse babies with distended stomachs, and drawings of villagers blinded by trachoma.

A second box contains a smartly bound volume of work, labeled with gold embossed type: “My Artwork from Childhood to Maturity, Larchmont 1938–1957.” Some of the work in this volume, bound in Pakistan, can indeed be dated to her earliest childhood and young adulthood. It is the kind of art only a mother could cherish and had undoubtedly been returned to Maryam in the wake of Myra’s death. Other drawings in this volume, all scenes from

Ahmad Khalil,

were labeled “additional illustrations made in Lahore” and dated 1969–1989. That Maryam had quietly returned to drawing in Pakistan may explain why she had mislabeled the volume and sent it to the Manuscripts and Archives Division. There it would be beyond the purview of a disapproving husband.

But it is the third box, the largest among them, that contains unbound oversize pencil drawings of even more recent vintage. Here the characters of the novel—Ahmad Khalil, his cousins, wife, and children, his Israeli guard—are all identified by name inscribed near their images. With one exception, all these drawings are captioned with quotations from the Qur’an, as if Maryam imagined that holy inscriptions might protect her from Allah’s anger at her transgression. The figures in these drawings crowd each other on the rough paper, their faces drawn with sadness, resignation, or rage. She clearly had no access to paint; I wondered how she managed to get the paper and how she managed to send the drawings to the library without her husband’s knowledge.

“From persecuted to persecutor, one of the darkest aspects of human nature,” Maryam wrote below the picture of the imprisoned Ahmad Khalil watched over by his prison guard, bearing a concentration camp tattoo. In her novel Maryam had captured the irony of the cruelties and injustices inflicted upon the Arab refugees by Jews who were only recently prisoners and refugees themselves.

The last drawing in the box is titled “Exodus: May 14, 1948.” It shows Ahmad Khalil in mourning for his murdered family and his village, grasping a long knife dripping with blood, as Iraq al-Manshiya explodes into flames behind him.

Underneath runs a new legend, not from the Qur’an. Instead, the caption conveys how persecution, retribution, and the notion of two civilizations in a fight to the death can circle around each other indefinitely, like a perpetual motion machine:

Western civilization is superior to Islamic civilization, we fellow Europeans must conquer and westernize these backward Arabs…

—Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, September 11, 2001

Upon reading that, I sat down to write a letter to Maryam Jameelah. I sent it to her care of her publisher and husband, Mohammad Yusuf Khan.