The Conquering Tide (86 page)

Read The Conquering Tide Online

Authors: Ian W. Toll

T

HROUGHOUT THE LONG DAY OF AIR OPERATIONS,

a steady 15-knot easterly wind had required the Americans to move east, toward Guam and away from the enemy.

54

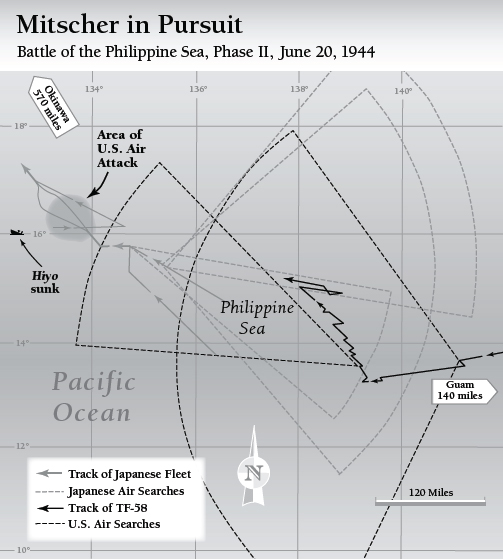

For the moment, the Japanese fleet lay well beyond the reach of a counterstrike. Spruance knew that one or two Japanese carriers had been torpedoed, but he did not yet know that they were gone. If they were crippled and afloat, as seemed likely, it should be possible to finish them off. With those considerations in mind, Spruance approved Mitscher's plan to chase the enemy into the west.

Ozawa had only intermittent radio contact with the commander in chief of the Combined Fleet during the chaotic afternoon of June 19. Toyoda had issued orders for a temporary withdrawal to the northwest. The fleet would refuel and then “advance and attack enemy task force in cooperation with Base Air Force.”

55

Though he had only 102 operational planes remaining on his carriers, including about forty on the

Zuikaku

, Ozawa believed that many of his missing airplanes must have landed on Guam. He also assumed, or perhaps hoped, that the Americans must have suffered grave losses in both ships and aircraft. Ozawa remained under the mistaken impression that Kakuta's land-based planes had taken a generous bite out of the American task force. His few returned pilots had reported that they had “succeeded in causing four carriers to emit black smoke.”

56

But on Toyoda's flagship

Oyodo

, at anchor in Japan's home waters, the Combined Fleet staff was gradually facing up to the magnitude of the Japanese defeat. It was time to get the surviving ships to safety. At 9:00 p.m., Admiral Toyoda signaled: “Task force will make a timely withdrawal depending upon the local situation, and move as its commander considers fit.”

57

On the twentieth, American air searches failed to find any sign of Ozawa's retreating fleet until 3:42 p.m., when an

Enterprise

TBF Avenger piloted by Lieutenant R. S. Nelson radioed a garbled contact report. The time and imputed distance put the enemy fleet about 270 miles northwest. Mitscher

signaled the task force: “Expect to launch everything we have, probably have to recover at night.”

58

Low whistles were heard in the squadron ready rooms as the pilots studied the charts and entered data into their plotting boards. Laden with fuel, bombs, and torpedoes, the American warplanes would fly to the edge of their maximum fuel radius. The afternoon was getting on, so they would return to the task force after nightfall. It was a dicey proposition. Very few American pilots had qualified for night carrier landings. Many would be forced to ditch at sea. But this was to be Mitscher's last opportunity to strike Ozawa, at least in this round, because the Task Force 58 destroyers did not have the fuel for another day's pursuit. He gave his order: “Launch the deckload strikes and prepare a second load.” Truman Hedding questioned it, alluding to the distance and risks, but Mitscher only replied, “I understand, but launch the deckload strikes.”

59

Mitscher put the word out: “The primary mission is to get the carriers.” On the ready room chalkboards, the three-word directive was written and underlined: “Get the carriers.”

60

At 4:21 p.m., Task Force 58 turned east, away from the enemy and into the wind, and began launching planes. Just eleven minutes were needed to get 216 planes aloftâeighty-five Hellcats, some to fly high cover and some carrying 500-pound bombs; fifty-four TBF Avengers, all but a few armed with bombs rather than the heavy aerial torpedoes; fifty-one SB2C Helldivers with 1,500-pound composite bomb loads; and twenty-six SBD Dauntless dive-bombers. (The SBDs were soon to be replaced; this was to be the last carrier combat mission in the aircraft's storied career.)

As the planes were launching, Nelson sent a corrected contact report. The enemy fleet, widely separated into three groups, was actually sixty miles farther west than Mitscher had assumed. Mitscher considered and rejected the option to cancel the attack and recall the planes. He decided to hold the second deckload strike in reserve for the following morning.

By 4:36 p.m., the 216-plane formation was on its way. Fuel limitations did not allow for a rendezvous into standard squadron or section formations. Planes joined up when and if opportunity offered in what James Ramage called “a running rendezvous.”

61

Fuel mixtures were leaned and engines throttled back to minimum power for level flight. According to Ensign Don Lewis of VB-10, stretching an aircraft's fuel reserve was as much art as science.

It was a matter of flying “gently,” of climbing little by little to altitude, of keeping the aircraft balanced by switching between auxiliary fuel tanks.

62

The outgoing formations droned along at about 130 to 140 knots. Many of the aviators later confessed that they were physically exhausted after a week and a half of intensive combat flight operations. The dive-bombers climbed to 20,000 feet, where the physical strain on the aircrew was severeâthe cockpits were arctic, men clapped their gloved hands to keep them warm, and ice crystals accumulated in their oxygen masks.

No one had any illusions. They all knew that they were going beyond normal fuel range and might be getting wet at the end of the day. Mitscher and the other task force commanders had proved that they would go to great lengths to rescue downed aviators. That bond of trust now paid dividends.

The leading planes overtook the trailing edge of the Japanese fleet at about 6:25 p.m., less than an hour before sunset. The pilots saw long white wakes, indicating that the enemy ships were moving at high speed. In the first (westernmost) group were six large fleet oilers and six destroyers. Flight leaders told their squadrons to ignore the tempting targets and continue flying northwest because their orders were to attack the “Charlie Victors” (carriers). About ten minutes later, the leading wave of planes reported many ships ahead, including carriers.

Ozawa had managed to get about eighty planes aloft, mostly Zero

fightersâno small feat considering the beating his air groups had suffered the previous day. F6Fs, flying high cover over the bomber squadrons, moved ahead to engage the enemy fighters. About twenty Zeros went down in the first few minutes of air combat. Commander Jackson D. Arnold of the

Hornet

Air Group directed all planes to attack the

Zuikaku

. Sinking the big flattop, Arnold told his pilots, “was their ticket home.”

63

There was neither time nor fuel to set up coordinated attacksâthey would just drop their noses and go straight into the heart of the enemy fleet.

Hal Buell led the

Hornet

Helldivers in a shallow dive toward the target, hoping to achieve surprise. Antiaircraft fire reached up toward them, but the first bursts were low. The Helldivers pushed over into a steep dive and flew through an intense, multicolored barrage. It was the heaviest antiaircraft fire that the veteran Buell had ever encountered. “In the lead plane I was a focal point, and with the mass of shells passing all about me, I felt like I was diving into an Iowa plains hailstorm. . . . Some threw out long tentacles of

flaming white phosphorus unlike anything I had ever seen before.”

64

The

Yorktown

's VB-1 Helldivers followed behind the

Hornet

planes and rained a dozen bombs down on the big carrier. Towers of whitewater rose on either side of the ship as bombs missed her narrowly, but two or three found the mark.

Zuikaku

burned fiercely and coasted to rest as her power cut out. F6Fs roared low over her flight deck in strafing runs and killed dozens of her crew.

The SBDs of VB-10 arrived over the fleet at 15,500 feet and began a high-speed breakup into their dives. In a shallow dive, with 200 knots airspeed, Don Lewis went over his checklist, shifted to low blower, and pushed over. He attacked the

Hiyo

. She went into a radical turn, and Lewis corkscrewed several times to keep the target in his sights. The dive, said Lewis, “seemed to take an eternity. Never had a dive taken so long.” Flying through a massive volume of antiaircraft fire, the flight deck looking “tremendous” beneath him, he released his bomb at 1,500 feet and pulled out and up.

65

A group of

Wasp

dive-bombers had paused to attack the fleet oilers, thirty or forty miles east of the main action. Two were so badly damaged that they had to be abandoned and scuttled. Other attackers planted bombs on the light carrier

Junyo

, the stern of the

Chiyoda

, a former seaplane tender, and the battleship

Haruna

. Four

Belleau Wood

Avengers armed with torpedoes dropped out of a cloud and made a high-speed run on the heavy carrier

Hiyo

, scoring at least one and possibly two torpedo hits. The

Hiyo

's crew lost control of the resulting fires and had to abandon her later that night. She went down by the bow a few minutes before 10:00 p.m., bringing to three the number of Japanese carriers destroyed in the two-day battle.

Zuikaku

suffered badly enough that her skipper ordered the crew to abandon ship, but the fires were finally brought under control and the order countermanded. For once, Japanese damage-control efforts were successful, and the badly damaged carrier managed to limp back to the Inland Sea.

Lightened by the absence of their bombs, the escaping planes flew through a deadly gauntlet of antiaircraft fire. The Japanese formation was spread very wide across the sea, so it was a long flight to exit the screen. Fleeing planes were rocked hard by nearby bursts, and columns of water shot up ahead and among them as the destroyers and cruisers fired their main batteries into their paths. Pilots flew down to wave-top level, pulled up, and kicked their rudders right and left, hoping to prevent the gunners from finding the range.

Buell's plane took a direct hit and almost went down. An antiaircraft shell blew a hole through the middle of his starboard wing, and a piece of shrapnel penetrated the cockpit and cut a gash across his back. The wing trailed a tail of fire, which began burning through the wing's aluminum skin, exposing the frame beneath. The wounded Buell forced the stick as far left as it would go in order to keep his unwieldy dive-bomber in level flight. (That the wounded Helldiver could fly at all, let alone fly all the way back to Task Force 58, was proof of its rugged construction.)

Admiral Ugaki recorded that the antiaircraft fire was so heavy, it took on a life of its own. Even after the American planes had left the scene, it continued sporadically into the night. “Most of the fire was aimed at stars,” he wrote. “Even within a single ship, orders were hard to deliver. Firing couldn't be stopped easily.”

66

On the long return flight, in gathering darkness, American warplanes coalesced into small groups. Adjusting their engine settings to “slow cruise,” they tried to coax every possible mile out of each gallon of remaining gasoline. One pilot, battling fatigue, breathed pure oxygen through his mask even though he was at just 2,000 feet altitude, hoping that it would give him energy to complete the mission. The radio circuits remained busy as pilots discussed their predicament. Hours passed. Fuel needles dipped toward empty. Entire sections or squadrons decided to ditch their planes in one location, reasoning that several rafts lashed together were easier to spot than a single one. Most of the aviators kept their cool, Vraciu recalled, but “some of them were breaking downâsobbingâon the air. It was a dark and black ocean out there. I could empathize with them, but it got so bad that I had to turn my radio off for a while.”

67

Even for those pilots with enough fuel to get home, it was no easy task to find the American fleet. Flying in darkness was a new experience for all but a few. Some were drawn off course by lightning flashes on the southern horizon. Those who flew long enough picked up a homing beaconâa faint signal through the earphonesâand followed it back to the fleet.

Admiral Mitscher had previously informed all Task Force 58 ships that they should, when ordered, point their searchlights vertically into the sky. Lighting up ships in enemy waters defied prevailing doctrine, and might have been fatal had there been Japanese submarines in the vicinity, but Mitscher felt obligated to accept the risks. The decision to turn on the

lights became an important part of Mitscher's legacy, a badge of his personal regard for his pilots. But the decision was not unprecedented, nor was it deemed especially controversial at the time. The prior week's action had allayed fears about the enemy air threat, and the enemy submarine threat had been reduced by the hunter-killer groups, which had destroyed six or seven Japanese boats in the previous ten days. During the Battle of Midway two years earlier, Spruance had ordered the

Enterprise

and

Hornet

lit up to recover aircraft returning from a late-day strike against the retreating Japanese fleet. To a historian who congratulated him for his courage in rendering that decision, Spruance later offered this comment: