The Conquering Tide (56 page)

Read The Conquering Tide Online

Authors: Ian W. Toll

Brooke, in restrained exasperation, reiterated his familiar arguments. He later complained to his diary that King had tried “to find every loophole he possibly can to divert troops to the Pacific!”

59

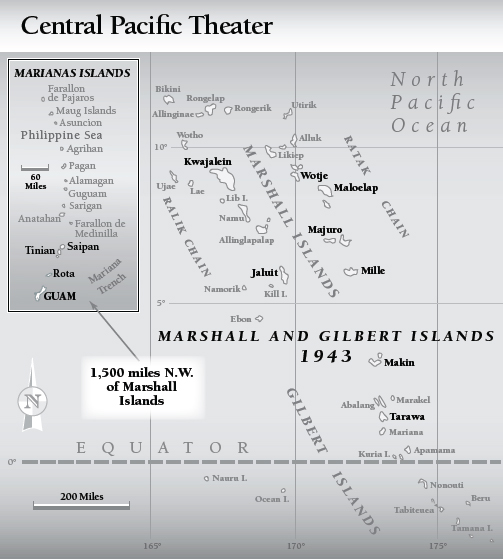

But with few forces actively engaged against the Japanese, the British lacked standing to shape strategy in the theater. Without quite saying it, Leahy, King, and Marshall intimated that the Pacific was now an American responsibility, and left no doubt that they would fight it on their own terms and according to their own schedule. In Trident's final conference documents, the American strategic proposals were enacted wholesale, including “Seizure of the Marshall and Caroline Islands” without reference to the timing of MacArthur's assault on Rabaul.

60

T

WO PARALLEL

P

ACIFIC CAMPAIGNS

, north and south of the equator, now had the imprimatur of the Allied high command. But Nimitz did not yet possess the sea or carrier air forces needed to wage a central Pacific offensive, and the troops in his theater required months of additional amphibious

training. From his South Pacific headquarters, Halsey was calling for reinforcements to carry his fight into the central Solomons. Nonetheless, King wanted hard deadlines for the central Pacific campaign. “In order that effective momentum of offensive operations can be attained and maintained,” he told his fellow chiefs on June 10, “firm timing must be set up for all areas.”

61

Four days later, the Joint Chiefs of Staff instructed Nimitz to prepare to invade the Marshall Islands with a tentative sailing date of November 15, 1943. MacArthur was to release the 1st Marine Division in time to participate in the operation, and most of Halsey's naval and amphibious forces would be shifted to Pearl Harbor as well. With unusual candor the chiefs acknowledged that the date was somewhat arbitraryâbut in the absence of deadlines “it is not repeat not practicable to provide able structure for our operations throughout the Pacific and Far East.”

62

Predictably outraged, MacArthur objected that the demands of his

CARTWHEEL

campaign precluded any transfers of troops or ships from his theater to Nimitz's. Indeed, MacArthur wanted (and would receive) covering support from the Pacific Fleet's new fast carrier task forces in raids against Rabaul, Truk, and other Japanese bases on the southern route. Likewise, Halsey was anxious about the withdrawal of aircraft from the SOPAC region for support of operations north of the equator. Diverting airpower from the drive on Rabaul, he warned Nimitz on June 25, “would seriously jeopardize our chances of success at what appears to be the most critical stage of the campaign.”

63

Without borrowing forces from the South Pacific, Nimitz could not realistically tackle the Marshalls until early 1944, and some on the CINCPAC planning staff counseled patience. They argued, not unreasonably, that the new offensive should await the arrival of a large fleet of

Essex

carriers, which could spearhead long leaps across ocean wastes and beat back enemy land-based air attacks. By February or March 1944, a much-expanded Fifth Fleet could simply steam into the Marshalls and seize the four or five largest Japanese bases in the group simultaneously. If the Japanese fleet came out to fight, the fast carrier task forces would willingly and confidently give battle.

But King wanted action in 1943. He insisted that the northern line of attack be opened

before

the final assault on Rabaul, so that the enemy could not concentrate his defenses against either prong of the westward advance. Enemy territory had to be taken, somewhere in the central Pacific, before the end of the year. Two competing suggestions were debated at CINCPAC

headquarters. Captain Forrest P. Sherman, the influential chief of staff to Vice Admiral John Henry Towers (Commander Air Forces, Pacific, or “COMAIRPAC”), circulated a plan to recapture Wake Island and employ it as a springboard for a later assault on the Marshalls, which lay about 500 miles south. Spruance favored opening the new campaign much farther south and east, where the fleet could count on greater land-based air support from rear bases in the South Pacific. He wanted to launch the new offensive in the Gilbert Islands, some 600 miles southeast of the Marshalls. Nimitz was swayed by his chief of staff's reasoning, and persuaded King in turn. COMINCH arranged the necessary Joint Chiefs of Staff directive on

July 20, 1943. The operation, code-named

GALVANIC

, called for the simultaneous capture of objectives in the Ellice Islands, the Gilbert Islands, and Nauru by November 15 of that year.

S

INCE HIS VICTORIOUS RETURN

from Midway a year earlier, Raymond Spruance had privately hoped for another major command at sea. But it was not the taciturn admiral's way to lobby for a job, and he was neither surprised nor disconcerted when Nimitz told him, as the two men walked to CINCPAC headquarters one morning in May 1943, “There are going to be some changes in the high command of the fleet. I would like to let you go, but unfortunately for you I need you here.”

In his version of the conversation, recalled years later, Spruance replied, “Well, the war is an important thing. I personally would like to have another crack at the Japs, but if you need me here, this is where I should be.”

The next morning, as the two went again on foot from house to office, Nimitz brought the subject up again. “I have been thinking this over during the night,” he said. “Spruance, you are lucky. I've decided that I am going to let you go, after all.”

64

Nimitz sold King on the assignment during their meeting in San Francisco later that month. On May 30, a dispatch from Navy Headquarters in Washington lifted Spruance to the rank of vice admiral. Shortly afterward, he was detached from the CINCPAC staff and placed in command of the Central Pacific Force, later designated the Fifth Fleet. It was the largest seagoing command in the history of the U.S. Navy.

Time was short. Spruance had little more than four months to plan the largest and most complex amphibious operation yet attempted. Naval forces and landing troops had to be collected from far-flung parts of the South Pacific and the mainland. His key commanders had not yet been named to their posts, nor had they even been identified. Writing the plan would be an immensely complicated and demanding job. Spruance moved quickly to recruit a chief of staff with the requisite experience and initiative. He chose an old friend and shipmate, Captain Charles J. “Carl” Moore, who was then serving in Washington as a member of Admiral King's war-planning staff. Spruance asked Moore to select the other key staff officers, poaching them from navy headquarters if he wished, but asked him to keep the headcount

to a manageable minimum. Moore arrived in Pearl Harbor on August 5 and moved into a spare bedroom in Nimitz and Spruance's house atop Makalapa Hill.

65

Spruance's command philosophy was to delegate any task that he did not absolutely have to do himself. He later observed, with worthy candor, “Looking at myself objectively, I think I am a good judge of men; and I know that I tend to be lazy about many things, so I do not try to do anything that I can pass down the line to someone more competent than I am to do it.”

66

Carl Moore would have agreed with the entirety of that judgment. Spruance did not micromanage; he picked good men, gave them authority, and held them accountable. He never failed to grasp the data he needed to render major decisions, but once those decisions were made, he dismissed from his mind the details of their execution. By refusing to absorb himself in such particulars, he kept his mind clear to consider the broadest problems of strategy and organization. Plausibly, Spruance did not need to work as hard as others because he possessed the sort of mind that took in and processed information more rapidly. Ernest King, who was no simpleton, attested that Spruance “was in intellectual ability unsurpassed among the flag officers of the United States Navy.”

67

His distinction as a seagoing commander, at the Battle of Midway in 1942 and with the Fifth Fleet later in the war, would seem to vindicate his hands-off approach.

It was also true, at least in a limited sense, that Spruance was lazy. He seemed to bore easily, and often resisted talking about the war. He was a compulsive walker, and tended to walk out of the office at all hours of the day, whether or not work remained to be done. He often took members of his staff along with him. Moore wrote about one such instance in a letter to his wife, composed three days after his arrival in Hawaii: “Raymond is up to his tricks already, and yesterday took me on an eight mile hike in the foothills. It was hot and a hard pull at times, and particularly so as we carried on a lively conversation all the way which kept me completely winded.”

68

Moore tried to engage the boss about the coming operation, but Spruance steered the conversation toward unrelated subjects and held forth on the virtues of physical fitness. A few days later Moore wrote his wife again: “Yesterday Raymond stepped up the pace and the distance and we covered over 10 miles in three hours. My right leg caught up with my left and both were wrecked by the time I got back. . . . If he can get me burned to a crisp or crippled from walking he will be completely happy.”

69

Spruance wanted Kelly Turner to command the amphibious fleet. It was not necessary to give the issue much thought. With a year of hard-earned experience in the South Pacific, Turner was the navy's preeminent amphibious specialist. Spruance knew him well, having served with him at sea and at the Naval War College. “I would like to get Admiral Kelly Turner from Admiral Halsey, if I can steal him,” he told Nimitz in June.

70

With the northern Solomons island-hopping campaign in high gear, Halsey was not keen to release Turner, so Nimitz made it simple. In a personal “Dear Bill” dated June 26, the CINCPAC explained that he had been ordered to wage a new offensive in the central Pacific: “This means I must have Turner report to me as soon as possible.”

71

When Turner came north, he brought several of his best staff officers with him, causing Halsey further heartburn.

Marine Major General Holland M. Smith would command the invasion troops, designated the Fifth Amphibious Corps (or “VAC”). Smith was one of the pioneers of amphibious warfare. He had persuaded the navy to adopt Andrew Higgins's shallow-draft boats as landing craft, and had successfully trained several divisions in amphibious operations at Camps Elliott and Pendleton in southern California. He had lobbied for a combat command in the Pacific, and was backed for the job by Secretary Knox and Admiral King. Nimitz did not know him well, but Spruance had worked with him in the mid-1930s, when both officers were stationed in the Caribbean. Nimitz offered him the job during an inspection tour of the South Pacific, and Smith readily accepted it.

Turner and Smith made a combustible pair. Both men were aggressive, ambitious, and overbearing. Both were respected authorities in the field of amphibious warfare, but had become accustomed to running things without competition or interference. Both were prone to fits of rage, and had earned nicknames as a result: “Terrible Turner” and “Howlin' Mad” Smith. Smith was exceptionally touchy about command relations between the navy and the Marine Corps. At Guadalcanal, Turner had offended General Vandegrift by infringing upon the latter's command prerogatives. During the planning of

GALVANIC

, Spruance sometimes wondered “whether we could get the operation planned out before there was an explosion between them.”

72

Arriving in Pearl Harbor the first week of September, Holland Smith was assigned quarters in a bungalow at the base of Makalapa Hill. The little house was beneath his rank, and he knew it. Always sensitive to any

trace of an insult to the Marine Corps, he coldly reminded the responsible naval officer that he was a major general, senior to most admirals at Pearl, and demanded more suitable quarters. The assignment was explained as an oversight, though Smith did not believe it had been; apologies were offered and the general was lodged in a grander house higher on the hill.

Smith had previously met Kelly Turner in Washington, when the latter was the navy's war plans chief. He found the admiral precise and courteous, like “an exacting schoolmaster,” and “affable in an academic manner,”

73

but he had also encountered Turner's famous temper. “He could be plain ornery. He wasn't called âTerrible Turner' without reason.”

74

For Operation

GALVANIC

, Turner expected to stand above Smith in the chain of command. That would be consistent with the model employed in Operation

WATCHTOWER

. But Smith wanted direct command of all amphibious troops throughout the operationâprior to, during, and after the landingâand wished to report directly to Spruance.