The Complete Yes Minister (70 page)

‘It might,’ she retorted, ‘if you threaten to tell what you know.’

I considered that for a moment. But, in fact, what do I know? I don’t know anything. At least, nothing I can prove. I’ve no hard facts at all. I know that the story is true simply because no one has denied it – but that’s not proof. I explained all this to Annie, adding that therefore I was in somewhat of a fix.

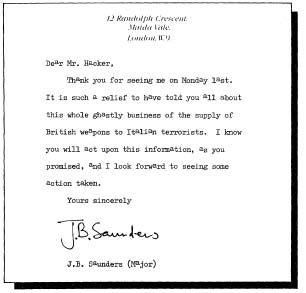

She saw the point. Then she handed me a letter. ‘I don’t think you realise just how big a fix you’re in. This arrived today. From Major Saunders.’

This letter is a catastrophe. Major Saunders can prove to the world that he told me about this scandal, and that I did nothing. And it is a photocopy – he definitely has the original.

And

it arrived Recorded Delivery. So I can’t say I didn’t get it.

it arrived Recorded Delivery. So I can’t say I didn’t get it.

I’m trapped. Unless Humphrey or Bernard can think of a way out.

September 12th

Bernard thought of a way out, thank God!

At our meeting first thing on Monday morning he suggested the Rhodesia Solution.

Humphrey was thrilled. ‘Well done Bernard! You excel yourself. Of course, the Rhodesia Solution. Just the job, Minister.’

I didn’t know what they were talking about at first. So Sir Humphrey reminded me of the Rhodesia oil sanctions row. ‘What happened was that a member of the government had been told about the way in which British companies were sanction-busting.’

‘So what did he do?’ I asked anxiously.

‘He told the Prime Minister,’ said Bernard with a sly grin.

‘And what did the Prime Minister do?’ I wanted to know.

‘Ah,’ said Sir Humphrey. ‘The Minister in question told the Prime Minister in such a way that the Prime Minister didn’t hear him.’

I couldn’t think what he and Bernard could possibly mean. Was I supposed to mumble at the PM in the Division Lobby, or something?

They could see my confusion.

‘You write a note,’ said Humphrey.

‘In very faint pencil, or what? Do be practical, Humphrey.’

‘It’s awfully obvious, Minister. You write a note that is susceptible to misinterpretation.’

I began to see. Light was faintly visible at the end of the tunnel. But what sort of note?

‘I don’t quite see

how

,’ I said. ‘It’s a bit difficult, isn’t it? “Dear Prime Minister, I have found that top-secret British bomb detonators are getting into the hands of Italian terrorists!” How do you misinterpret that?’

how

,’ I said. ‘It’s a bit difficult, isn’t it? “Dear Prime Minister, I have found that top-secret British bomb detonators are getting into the hands of Italian terrorists!” How do you misinterpret that?’

‘You can’t,’ said Humphrey, ‘so don’t write that. You use a more . . . circumspect style.’ He chose the word carefully. ‘You must avoid any mention of bombs and terrorists and all that sort of thing.’

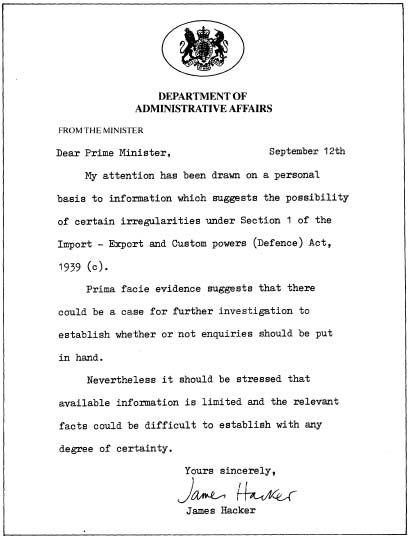

I saw that, of course, but I didn’t quite see how to write such an opaque letter. But it was no trouble to Humphrey. He delivered a draft of the letter to my red box for me tonight. Brilliant.

[

We have managed to find the letter, in the Cabinet Office files from Number Ten, subsequently released under the Thirty-Year Rule – Ed

.]

We have managed to find the letter, in the Cabinet Office files from Number Ten, subsequently released under the Thirty-Year Rule – Ed

.]

[

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

The letter is masterly because not only does it draw attention to the matter in a way which is unlikely to be remarked, but it also suggests that

someone else

should do something about it, and ends with a sentence implying that even if they do, they won’t get anywhere. So if at any future date there is an enquiry I’ll be in the clear, and yet everyone will be able to understand that a busy PM might not have grasped the implications of such a letter. I signed it at once.

someone else

should do something about it, and ends with a sentence implying that even if they do, they won’t get anywhere. So if at any future date there is an enquiry I’ll be in the clear, and yet everyone will be able to understand that a busy PM might not have grasped the implications of such a letter. I signed it at once.

September 13th

I congratulated Humphrey this morning on his letter, and told him it was very unclear. He was delighted.

He had further plans all worked out. We will not send the letter for a little while. We’ll arrange for it to arrive at Number Ten on the day that the PM is leaving for an overseas summit. This will mean that there will be further doubt about whether the letter was read by the PM or by the acting PM, neither of whom will remember of course.

This is the finishing touch, and will certainly ensure that the whole thing is written off as a breakdown in communications. So everyone will be in the clear, and everyone can get on with their business.

Including the red terrorists.

And I’m afraid I’m a little drunk tonight, or I wouldn’t have just dictated that deeply depressing sentence.

But it’s true. And I’ve been formulating some theories about government. Real practical theories, not the theoretical rubbish they teach in Universities.

In government you must always try to do the right thing. But whatever you do, you must never let anyone catch you trying to do it. Because doing right’s wrong, right?

Government is about principle. And the principle is: don’t rock the boat. Because if you do rock the boat all the little consciences fall out. And we’ve all got to hang together. Because if we don’t we’ll all be hanged separately. And I’m hanged if I’ll be hanged.

Why should I be? Politics is about helping others. Even if it means helping terrorists. Well, terrorists are others, aren’t they? I mean, they’re not

us

, are they?

us

, are they?

So you’ve got to follow your conscience. But you’ve also got to know where you’re going. So you

can’t

follow your conscience because it may not be going the same way that you are.

can’t

follow your conscience because it may not be going the same way that you are.

Aye, there’s the rub.

I’ve just played back today’s diary entry on my cassette recorder. And I realise that I am a moral vacuum too.

September 14th

Woke up feeling awful. I don’t know whether it was from alcoholic or emotional causes. But certainly my head was aching and I felt tired, sick, and depressed.

But Annie was wonderful. Not only did she make me some black coffee, she said all the right things.

I was feeling that I was no different from Humphrey and all that lot in Whitehall. She wouldn’t have that at all.

‘He’s lost his sense of right and wrong,’ she said firmly. ‘You’ve still got yours.’

‘Have I?’ I groaned.

‘Yes. It’s just that you don’t use it much. You’re a sort of whisky priest. You do at least know when you’ve done the wrong thing.’

She’s right. I

am

a sort of whisky priest. I may be immoral but I’m not amoral. And a whisky priest – with that certain air of raffishness of Graham Greene, of Trevor Howard, that

je ne sais quoi

– is not such a bad thing to be.

am

a sort of whisky priest. I may be immoral but I’m not amoral. And a whisky priest – with that certain air of raffishness of Graham Greene, of Trevor Howard, that

je ne sais quoi

– is not such a bad thing to be.

Is it?

1

Her Majesty’s Government.

Her Majesty’s Government.

2

‘No man is an Island, entire of itself . . . Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankind; And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.’ – John Donne.

‘No man is an Island, entire of itself . . . Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankind; And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.’ – John Donne.

3

In conversation with the Editors.

In conversation with the Editors.

20

The Middle-Class Rip-off

September 24th

After my constituency surgery this morning, which I used to do every other Saturday but which I can now manage less often since I became a Minister, I went off to watch Aston Wanderers’ home match.

It was a sad experience. The huge stadium was half empty. The players were a little bedraggled and disheartened, there was a general air of damp and decay about the whole outing.

I went with Councillor Brian Wilkinson, Chairman of the local authority’s Arts and Leisure Committee and by trade an electrician’s mate at the Sewage Farm, and Harry Sutton, the Chairman of the Wanderers, a local balding businessman who’s done rather well on what he calls ‘import and export’. Both party stalwarts.

Afterwards they invited me into the Boardroom for a noggin. I accepted enthusiastically, feeling the need for a little instant warmth after braving the elements in the Directors’ Box for nearly two hours.

I thanked Harry for the drink and the afternoon’s entertainment.

‘Better enjoy it while the club’s still here,’ he replied darkly.

I remarked that we’d always survived so far.

‘It’s different this time,’ said Brian Wilkinson.

I realised that the invitation was not purely social. I composed myself and waited. Sure enough, something was afoot. Harry stared at Brian and said, ‘You’d better tell him.’ Wilkinson threw a handful of peanuts into his mouth, mixed in some Scotch, and told me.

‘I’ll not mince words. We had an emergency meeting of the Finance Committee last night, Aston Wanderers is going to have to call in the receiver.’

‘Bankruptcy?’ I was shocked. I mean, I knew that football clubs were generally in trouble, but this really caught me unawares.

Harry nodded. ‘The final whistle. We need one and a half million quid, Jim.’

‘Peanuts,’ said Brian.

‘No thank you,’ I said, and then realised that he was describing the sum of one and a half million pounds.

‘Government wastes that much money every thirty seconds,’ Brian added.

As a member of the government, I felt forced to defend our record. ‘We do keep stringent control on expenditure.’

It seemed the wrong thing to say. They both nodded, and agreed that our financial control was so stringent that perhaps it was lack of funds for the fare which had prevented my appearance at King Edward’s School prize-giving. I explained – thinking fast – that I’d had to answer Questions in the House that afternoon.

‘Your secretary said you had some committee meeting.’

Maybe I did. I can’t really remember that kind of trivial detail. Another bad move. Harry said, ‘You know what people round here are saying? That it’s a dead loss having a Cabinet Minister for an MP. Better off with a local lad who’s got time for his constituency.’

The usual complaint. It’s so unfair! I can’t be in six places at once, nobody can. But I didn’t get angry. I just laughed it off and said it was an absurd thing to say.

Brian asked why.

‘There are great advantages to having your MP in the Cabinet,’ I told him.

‘Funny we haven’t noticed them, have we, Harry?’

Harry Sutton shook his head. ‘Such as?’

‘Well . . .’ And I sighed. They always do this to you in your constituency, they feel they have to cut you down to size, to stop you getting too big for your boots, to remind you that you need them to re-elect you.

‘It reflects well on the constituency,’ I explained. ‘And it’s good to have powerful friends. Influence in high places. A friend in need.’

Harry nodded. ‘Well, listen ’ere, friend – what we need is one and a half million quid.’

I had never imagined that they thought I could solve their financial problems.

Was

that what they thought, I wondered? So I nodded non-committally and waited.

Was

that what they thought, I wondered? So I nodded non-committally and waited.

‘So will you use all that influence to help us?’ asked Harry.

Clearly I had to explain the facts of life to them. But I had to do it with tact and diplomacy. And without undermining my own position.

‘You see,’ I began carefully, ‘when I said

influence

I meant the more, er, intangible sort. The indefinable, subtle value of an input into broad policy with the constituency’s interest in mind.’

influence

I meant the more, er, intangible sort. The indefinable, subtle value of an input into broad policy with the constituency’s interest in mind.’

Harry was confused. ‘You mean no?’

I explained that anything I can do in a general sense to further the cause I would certainly do. If I could. But it’s scarcely possible for me to pump one and a half million into my local football club.

Harry turned to Brian. ‘He means no.’

Brian Wilkinson helped himself to another handful of peanuts. How does he stay so

thin

? He addressed me through the newest mouthful, a little indistinctly.

thin

? He addressed me through the newest mouthful, a little indistinctly.

‘There’d be a lot of votes in it. All the kids coming up to eighteen, too. You’d be the hero of the constituency. Jim Hacker, the man who saved Aston Wanderers. Safe seat for life.’

‘Yes,’ I agreed. ‘That might just strike the press too. And the opposition. And the judge.’

They stared at me, half-disconsolately, half-distrustfully. Where, they were wondering, was all that power that I’d been so rashly talking about a few minutes earlier? Of course the truth is that, at the end of the day, I do indeed have power (of a sort) but not to really

do

anything. Though I can’t expect them to understand that.

do

anything. Though I can’t expect them to understand that.

Other books

The Trouble with Tulip by Mindy Starns Clark

The Right Side of Wrong by Reavis Wortham

Billionaire Brothers 2 : Love Has A Name by S. Ann Cole

Engaging Men by Lynda Curnyn

Room Service by Vanessa Stark

HUGE X2 by Stephanie Brother

The Holy Thief by William Ryan

Rogue Stallion (Chrome Horsemen MC Book 2) by Carmen Faye

Pack Alpha by Crissy Smith

Slocum 421 by Jake Logan