The Complete Yes Minister (63 page)

I told her that the allegations she was making were the symptoms of a very sick society for which the media must take their share of the blame. I demanded to know why she wanted to put thousands of British jobs at risk. She had no answer. [

Naturally, as she did not want to put thousands of British jobs at risk – Ed

.] I told her that I would be calling on the Press Council to censure the press for a disgraceful breach of professional ethics in running the story.

Naturally, as she did not want to put thousands of British jobs at risk – Ed

.] I told her that I would be calling on the Press Council to censure the press for a disgraceful breach of professional ethics in running the story.

‘Indeed,’ I continued, rather superbly I thought, ‘the Council, and the House of Commons itself must surely be concerned about the standards that have applied in this shameful episode, and pressure will be brought to bear to ensure that this type of gutter press reporting is not repeated.’

She looked stunned. She was completely unprepared for my counter-attack, as I thought she would be.

Nervously she collected herself and asked her second question, with a great deal less confidence, I was pleased to see. ‘This rosewater jar, apparently presented to you in Qumran?’

‘Yes?’ I snapped, belligerently.

‘Well . . .’ she panicked but continued, ‘I saw it in your house actually.’

‘Yes,’ I replied, ‘we’re keeping it there temporarily.’

‘Temporarily?’

‘Oh yes,’ I was doing my ingenuous routine now. ‘It’s very valuable, you see.’

‘But Mrs Hacker said it was an imitation.’

I laughed. ‘Burglars, you silly girl. Burglars! We didn’t want gossip going around. Until we’ve got rid of it.’

Now she was completely confused. ‘Got rid of it?’

‘Of course. I’m presenting it to our local museum when we get back to the constituency on Saturday. Obviously I can’t keep it. Government property, you know.’ And then I came out with my master stroke. ‘Now – what was your question?’

She had nothing else to say. She said it was nothing, it was all right, everything was fine. I charmingly thanked her for dropping in, and ushered her out.

Humphrey was full of admiration.

‘Superb, Minister.’

And Bernard was full of gratitude.

‘Thank you, Minister.’

I told them it was nothing. After all, we have to stick by our friends. Loyalty is a much underrated quality. I told them so.

‘Yes Minister,’ they said, but somehow they didn’t look all that grateful.

1

Central Office of Information.

Central Office of Information.

2

Financial Times

.

Financial Times

.

3

In conversation with the Editors.

In conversation with the Editors.

4

In conversation with the Editors.

In conversation with the Editors.

18

The Bed of Nails

[

In politics, August is known as the ‘silly season’. This is a time when voters are away on holiday, and trivial issues are pushed in the forefront of the press in order to sell newspapers to holidaymakers. It is also the time when the House of Commons has risen for the summer recess and is thus an excellent time for the government to announce new or controversial measures about which the House of Commons cannot protest until they reconvene in October – by which time most political events that took place in August would be regarded as dead ducks by the media

.

In politics, August is known as the ‘silly season’. This is a time when voters are away on holiday, and trivial issues are pushed in the forefront of the press in order to sell newspapers to holidaymakers. It is also the time when the House of Commons has risen for the summer recess and is thus an excellent time for the government to announce new or controversial measures about which the House of Commons cannot protest until they reconvene in October – by which time most political events that took place in August would be regarded as dead ducks by the media

.

It follows that August is also the time when Cabinet Ministers are most off their guard. Members of Parliament are not at hand to question them or harass them, and the Ministers themselves – secure from the unlikely event of an August reshuffle and secure from serious press coverage of their activities – relax more than they should

.

.

Perhaps this is the explanation of the transport policy crisis, which very nearly led to Hacker taking on one of the most unpopular jobs in Whitehall. How he evaded it is a tribute to the shrewd guiding hand of Sir Humphrey, coupled with Hacker’s own growing political skills

.

.

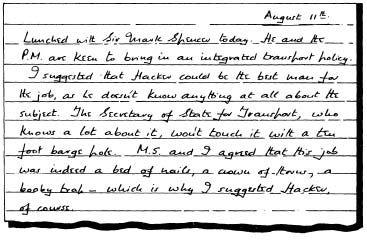

Early in the month a meeting took place at Ten Downing Street between Sir Mark Spencer, the Prime Minister’s Chief Special Adviser, and Sir Arnold Robinson, the Secretary of the Cabinet. Sir Mark’s files contain no reference to this meeting, but as he was not a career civil servant this is not surprising. But Sir Arnold Robinson’s diary, recently found in the Civil Service archives Walthamstow, reveal a conspiracy in the making – Ed

.]

.]

Lunched with Sir Mark Spencer today. He and the PM are keen to bring in an integrated transport policy.

I suggested that Hacker could be the best man for the job, as he doesn’t know anything at all about the subject. The Secretary of State for Transport, who knows a lot about it, won’t touch it with a ten foot barge pole. M.S. and I agreed that this job was indeed a bed of nails, a crown of thorns, a booby trap – which is why I suggested Hacker, of course.

He is ideally qualified, as I explained to M.S., because the job needs a particular talent – lots of activity, but no actual achievement.

At first M.S. couldn’t see how to swing it on Hacker. The answer was obvious: we had to make it seem like a special honour.

The big problem was to get Hacker to take it on before Humphrey Appleby hears of it, because there’s no doubt that Old Humpy would instantly smell a rat. ‘

Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes

’

1

he would be sure to say, though he’d probably have to say it in English for Hacker’s benefit as Hacker went to the LSE.

2

Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes

’

1

he would be sure to say, though he’d probably have to say it in English for Hacker’s benefit as Hacker went to the LSE.

2

It seemed clear that we had to get a commitment today, especially as my departure for the Florida Conference on ‘Government and Participation’ is both imminent and urgent, tomorrow at the latest. [

During the 1970s and 1980s it was the custom for senior government officials to send themselves off on futile conferences to agreeable resorts at public expense during the month of August – Ed

.]

During the 1970s and 1980s it was the custom for senior government officials to send themselves off on futile conferences to agreeable resorts at public expense during the month of August – Ed

.]

Hacker came to meet us at tea-time. I had resolved to flatter him, which almost invariably leads to success with politicians. M.S. and I agreed therefore that we would give the job the title of Transport Supremo, which was a lot more attractive than Transport Muggins.

I was also careful not to inform him in advance of the purpose of the meeting, partly because I did not want him to have the opportunity to discuss it with Humpy, and partly because I knew he would be anxious about being summoned to Number Ten. This would surely make him more pliable.

Events turned out precisely as I anticipated. He knew nothing whatever about transport, floundered hopelessly, was flattered to be asked and accepted the job.

It is fortunate that I shall be leaving for the country tonight, before Humpy gets to hear about all this.

[

It is interesting to compare the above recollections with Hacker’s account of the same day’s events in his diary – Ed

.]

It is interesting to compare the above recollections with Hacker’s account of the same day’s events in his diary – Ed

.]

August 11th

An absolutely splendid day today, with a big boost for my morale.

I was summoned to meet Mark Spencer at Number Ten. Naturally I was a bit wary, especially as I knew the PM hadn’t been awfully pleased to hear about that business with the rosewater jar, even though no harm came of it all in the end. I thought I might be in for a bit of a wigging, for when I got there I was met by Arnold Robinson, the Cabinet Secretary.

However, the meeting was for quite a different purpose – I’ve been promoted.

Arnold kicked off by saying they wanted to offer me something that was rather an honour. For a split second I was horrified – I thought they were telling me I was to be kicked upstairs. It was a nasty moment. But, in fact, they want to put me in charge of a new integrated national transport policy.

They asked me for my views on transport. I had none, but I don’t think they realised because I carefully invited them to explain themselves further. I’m sure they thought that I was merely playing my cards close to my chest.

‘We’ve been discussing a national integrated transport policy,’ they said.

‘Well, why not?’ I replied casually.

‘You’re in favour?’ enquired Sir Arnold quickly.

I thought the answer required was ‘yes’ but I wasn’t yet sure so I contented myself by looking enigmatic. I’m sure that they were by now convinced that I was sound, because Sir Mark continued: ‘Unfortunately, public dissatisfaction with the nationalised transport industries is now at a high enough level to worry the government, as you know.’

Again he waited. ‘Can you go on?’ I enquired.

He went on. ‘We need a policy.’ I nodded sagely. ‘It’s no good just blaming the management when there’s an R in the month and blaming the unions the rest of the time.’

Sir Arnold chipped in. ‘And unfortunately now they’ve all got together. They all say that it’s all the government’s fault – everything that goes wrong is the result of not having a national transport policy.’

This was all news to me. I thought we had a policy. As a matter of fact, I specifically recall that in our discussions prior to the writing of our manifesto we decided that our policy was not to have a policy. I said so.

Sir Mark nodded. ‘Be that as it may,’ he grunted, ‘the PM now wants a

positive

policy.’

positive

policy.’

I wished Sir Mark had said so earlier. But I can take a hint, and it was not too late. ‘Ah, the PM, I see.’ I nodded again. ‘Well, I couldn’t agree more, I’ve always thought so myself.’

Sir Arnold and Sir Mark looked pleased, but I still couldn’t see what it had to do with me. I assumed that it was a Department of Transport matter. Sir Arnold disabused me.

‘Obviously the Transport Secretary would love to get his teeth into the job, but he’s a bit too close to it all.’

‘Can’t see the wood for the trees,’ said Sir Mark.

‘Needs an open mind. Uncluttered,’ added Sir Arnold.

‘So,’ said Sir Mark, ‘the PM has decided to appoint a Supremo to develop and implement a national transport policy.’

A

Supremo

. I asked if I were the PM’s choice. The knights nodded. I must admit I felt excited and proud and really rather overwhelmed by this extraordinary good piece of news. And there were more compliments to come.

Supremo

. I asked if I were the PM’s choice. The knights nodded. I must admit I felt excited and proud and really rather overwhelmed by this extraordinary good piece of news. And there were more compliments to come.

‘It was decided,’ said Sir Mark, ‘that you had the most open mind of all.’

‘And the most uncluttered,’ added Sir Arnold. They really were grovelling.

I naturally responded cautiously. Firstly because I simply couldn’t imagine what the job entailed, and secondly it’s always good to play hard to get when you’re in demand. So I thanked them for the honour, agreed that it was a pretty vital and responsible job, and asked what it entailed.

‘It’s to help the consumer,’ said Sir Mark. Though when Sir Arnold laboriously pointed out that helping the consumer was always a vote-winner, I reminded him firmly that I was interested purely because I saw it as my duty to help. My sense of public duty.

During the conversation it gradually became clear what they had in mind. All kinds of idiocies have occurred in the past, due to a lack of a natural integrated policy. Roughly summarising now, Sir Mark and Sir Arnold were concerned about:

Motorway planning:

Our motorways were planned without reference to railways, so that now there are great stretches of motorway running alongside already existing railways.

Our motorways were planned without reference to railways, so that now there are great stretches of motorway running alongside already existing railways.

As a result, some parts of the country are not properly served at all.

The through-ticket problem:

If, for instance, you want to commute from Henley to the City, you have to buy a British Rail ticket to Paddington and then buy an underground ticket to the Bank.

If, for instance, you want to commute from Henley to the City, you have to buy a British Rail ticket to Paddington and then buy an underground ticket to the Bank.

Timetables:

The complete absence of combined bus and railway timetables.

The complete absence of combined bus and railway timetables.

Airport Links:

Very few. For instance, there’s a British Rail Western Region line that runs less than a mile north of Heathrow – but no link line.

Very few. For instance, there’s a British Rail Western Region line that runs less than a mile north of Heathrow – but no link line.

Connections:

Bus and train services don’t connect up, all over London.

Bus and train services don’t connect up, all over London.

Sir A. and Sir M. outlined these problems briefly. They added that there are probably problems outside London too, although understandably they didn’t know about them.

The possibilities are obviously great, and it’s all very exciting. I suggested having a word with Humphrey before I accepted responsibility, but they made it plain that they wanted

my

opinion and approval. Not his. Rather flattering, really. Also, it shows that they have finally realised that I’m not a straw man – I really run my Department, not like

some

Ministers.

my

opinion and approval. Not his. Rather flattering, really. Also, it shows that they have finally realised that I’m not a straw man – I really run my Department, not like

some

Ministers.

Furthermore it transpired that the PM was due to leave for the airport in thirty minutes on the long trip involving the Ottawa Conference, and the opening of the UN General Assembly in New York, and then on to the meeting in Washington.

Jokingly I asked, ‘Who’s going to run the country for the next week?’ but Sir Arnold didn’t seem awfully amused.

Sir Mark asked if he could give the PM the good news that I had taken on the job on the way to the airport.

Graciously, I agreed.

Other books

Baxter by Ellen Miles

Chance the Winds of Fortune by Laurie McBain

Friends and Lovers by June Francis

The Story of Gawain and Ragnell by Ruth Nestvold

Julius Caesar by Ernle Bradford

Zen and the Art of Vampires by Katie MacAlister

Lola Montez Conquers the Spaniards by Kit Brennan

Hail Mary Baby: A Secret Baby Sports Romance by Kara Hart

Alpha Bait by Sam Crescent