The Complete Yes Minister (39 page)

This was news to me. I asked how it was done.

‘You discredit them,’ he explained simply.

How? I made notes as he spoke. It occurred to me, that his technique could be useful for discrediting some of the party’s more idiotic research papers.

Stage one: The public interest

1) You hint at security considerations.

2) You point out that the report could be used to put unwelcome pressure on government because it might be misinterpreted. [

Of course, anything might be misinterpreted. The Sermon on the Mount might be misinterpreted. Indeed, Sir Humphrey Appleby would almost certainly have argued that, had the Sermon on the Mount been a government report, it should certainly not have been published on the grounds that it was a thoroughly irresponsible document: the sub-paragraph suggesting that the meek will inherit the earth could, for instance, do irreparable damage to the defence budget – Ed

.]

Of course, anything might be misinterpreted. The Sermon on the Mount might be misinterpreted. Indeed, Sir Humphrey Appleby would almost certainly have argued that, had the Sermon on the Mount been a government report, it should certainly not have been published on the grounds that it was a thoroughly irresponsible document: the sub-paragraph suggesting that the meek will inherit the earth could, for instance, do irreparable damage to the defence budget – Ed

.]

3) You then say that it is better to wait for the results of a wider and more detailed survey over a longer time-scale.

4) If there is no such survey being carried out, so much the better. You commission one, which gives you even more time to play with.

Stage two: Discredit the evidence that you are not publishing

This is, of course, much easier than discrediting evidence that you

do

publish. You do it indirectly, by press leaks. You say:

do

publish. You do it indirectly, by press leaks. You say:

(a) that it leaves important questions unanswered

(b) that much of the evidence is inconclusive

(c) that the figures are open to other interpretations

(d) that certain findings are contradictory

(e) that some of the main conclusions have been questioned

Points (a) to (d) are bound to be true. In fact, all of these criticisms can be made of a report without even reading it. There are, for instance, always

some

questions unanswered – such as the ones they haven’t asked. As regards (e), if some of the main conclusions have not been questioned, question them! Then they have.

some

questions unanswered – such as the ones they haven’t asked. As regards (e), if some of the main conclusions have not been questioned, question them! Then they have.

Stage three: Undermine the recommendations

This is easily done, with an assortment of governmental phrases:

(a) ‘not really a basis for long-term decisions . . .’

(b) ‘not sufficient information on which to base a valid assessment . . .’

(c) ‘no reason for any fundamental rethink of existing policy . . .’

(d) ‘broadly speaking, it endorses current practice . . .’

These phrases give comfort to people who have not read the report and who don’t want change – i.e. almost everybody.

Stage four: If stage three still leaves doubts, then Discredit The Man Who Produced the Report

This must be done OFF THE RECORD. You explain that:

(a) he is harbouring a grudge against the government

(b) he is a publicity seeker

(c) he’s trying to get his knighthood

(d) he is trying to get his chair

(e) he is trying to get his Vice-Chancellorship

(f) he used to be a consultant to a multinational company

or

or

(g) he wants to be a consultant to a multinational company

June 9th

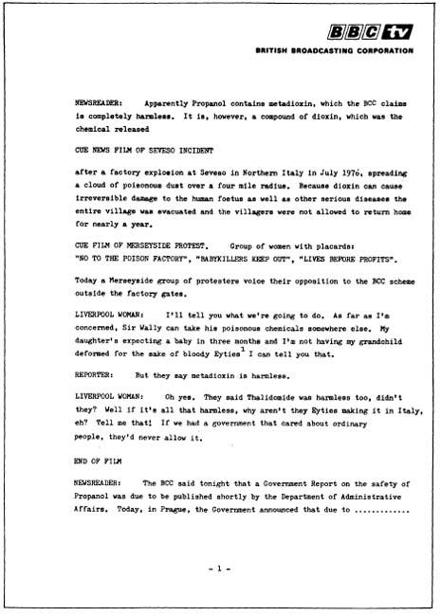

Today the Propanol plan reached the television news, damn it. Somehow some environmental group got wind of the scheme and a row blew up on Merseyside.

The TV newsreader – or whoever writes what the newsreader reads – didn’t help much either. Though he didn’t say that Propanol was dangerous, he somehow managed to imply it – using loaded words like ‘claim’.

[

We have found the transcript of the BBC Nine O’Clock News for 9 June. The relevant item is shown below Hacker seems to have a reasonable point – Ed

.]

We have found the transcript of the BBC Nine O’Clock News for 9 June. The relevant item is shown below Hacker seems to have a reasonable point – Ed

.]

[

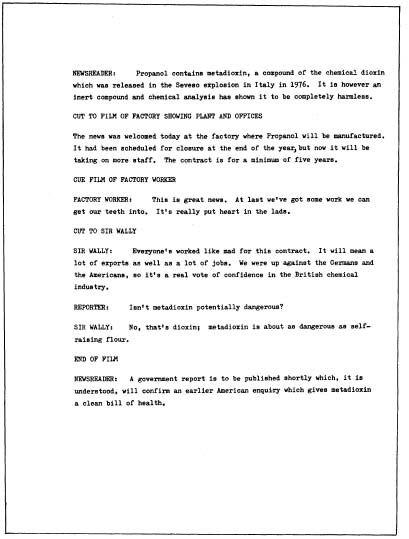

We asked an old BBC current affairs man how the News would have treated the item if they had been in favour of the scheme, and we reproduce his ‘favourable’ version to compare with the actual one – Ed

.]

We asked an old BBC current affairs man how the News would have treated the item if they had been in favour of the scheme, and we reproduce his ‘favourable’ version to compare with the actual one – Ed

.]

June 10th

I summoned Humphrey first thing this morning. I pointed out that metadioxin is dynamite.

He answered me that it’s harmless.

I disagreed. ‘It may be harmless chemically,’ I said, ‘but it’s lethal politically.’

‘It can’t hurt anyone,’ he insisted.

I pointed out that it could finish me off.

No sooner had we begun talking than Number Ten was on the phone. The political office. Joan Littler had obviously made sure that Number Ten watched the Nine O’Clock News last night.

I tried to explain that this was merely a little local difficulty, and there were exports and jobs prospects. They asked how many jobs: I had to admit that it was only about ninety – but well-paid jobs, and in an area of high unemployment.

None of this cut any ice with Number Ten – I was talking to the Chief Political Adviser, but doubtless he was acting under orders. There was no point in fighting this particular losing battle with the PM, so I muttered (as Humphrey was listening, and Bernard was probably listening-in) that I was coming round to their point of view,

i.e

. that there was a risk to three or four marginals.

i.e

. that there was a risk to three or four marginals.

I rang off. Humphrey was eyeing me with a quizzical air.

‘Humphrey,’ I began carefully, ‘something has just struck me.’

‘I noticed,’ he replied dryly.

I ignored the wisecrack. I pointed out that there were perfectly legitimate arguments against this scheme. A loss of public confidence, for instance.

‘You mean votes,’ he interjected.

I denied it, of course. I explained that I didn’t exactly mean votes. Votes in themselves are not a consideration. But

the public will

is a valid consideration. We are a democracy. And it looks as if the public are against this scheme.

the public will

is a valid consideration. We are a democracy. And it looks as if the public are against this scheme.

‘The public,’ said Sir Humphrey, ‘are ignorant and misguided.’

‘What do you mean?’ I demanded. ‘It was the public who elected me.’

There was a pointed silence.

Then Sir Humphrey continued: ‘Minister, in a week it will all have blown over, and in a year’s time there will be a safe and successful factory on Merseyside.’

‘A week is a long time in politics,’ I answered.

1

1

‘A year is a short time in government,’ responded Sir Humphrey.

I began to get cross.

He

may be in government. But I’m in politics. And the PM is not pleased.

He

may be in government. But I’m in politics. And the PM is not pleased.

Humphrey then tried to tell me that I was putting party before country. That hoary old cliché again. I told him to find a new one.

Bernard said that a new cliché could perhaps be said to be a contradiction in terms. Thank you, Bernard, for all your help!

I made one more attempt to make Humphrey understand. ‘Humphrey,’ I said, ‘you understand nothing because you lead a sheltered life. I want to survive. I’m not crossing the PM.’

He was very bitter. And very insulting. ‘Must you always be so concerned with climbing the greasy pole?’

I faced the question head on. ‘Humphrey,’ I explained, ‘the greasy pole is important. I have to climb it.’

‘Why?’

‘Because,’ I said, ‘it’s there.’

June 11th

Today there was an astonishing piece in

The Times

. A leak.

The Times

. A leak.

I was furious.

I asked Bernard how

The Times

knows the wording of the Henderson Report before I do.

The Times

knows the wording of the Henderson Report before I do.

‘There’s been a leak, Minister,’ he explained.

The boy’s a fool. Obviously there’s been a leak. The question is, who’s been leaking?

On second thoughts, perhaps he’s not a fool. Perhaps he knows. And can’t or won’t tell.

‘It’s labelled “Confidential”,’ I pointed out.

‘At least it wasn’t labelled “Restricted”,’ he said. [

RESTRICTED means it was in the papers yesterday. CONFIDENTIAL means it won’t be in the papers till today – Ed

.]

RESTRICTED means it was in the papers yesterday. CONFIDENTIAL means it won’t be in the papers till today – Ed

.]

I decided to put Bernard on the spot. ‘Who leaked this? Humphrey?’

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘I’m sure he didn’t.’

‘Are you?’ I asked penetratingly.

‘Well . . . he probably didn’t.’

‘No?’ I was at my most penetrating.

‘Well,’ said Bernard with a sheepish smile, ‘it

might

have been someone else.’

might

have been someone else.’

‘These leaks are a disgrace,’ I told him. ‘And people think that it’s politicians that leak.’

‘It has been known, though, hasn’t it?’ said Bernard carefully.

‘In my opinion,’ I said reproachfully, ‘we are much more leaked against than leaking.’

I then read

The Times

story carefully through. It contained a number of phrases that I could almost hear Humphrey dictating: ‘Political cowardice to reject the BCC proposal’ . . . ‘Hacker has no choice’, etc.

The Times

story carefully through. It contained a number of phrases that I could almost hear Humphrey dictating: ‘Political cowardice to reject the BCC proposal’ . . . ‘Hacker has no choice’, etc.

It was clear that, by means of this leak, Humphrey thinks that he has now committed me to this scheme.

Well, we shall see!

June 14th

I got my copy of the Henderson Report on Saturday, only a day after

The Times

got theirs. Not bad.

The Times

got theirs. Not bad.

The Report gives me no way out of the Propanol scheme. At least, none that I can see at the moment. It says it’s a completely safe chemical.

On the other hand,

The Times

commits me to nothing. It is, after all, merely an unofficial leak of a draft report.

The Times

commits me to nothing. It is, after all, merely an unofficial leak of a draft report.

Sir Wally McFarlane was my first appointment of the day. Humphrey came too – surprise, surprise!

And they were both looking excessively cheerful.

I asked them to sit down. Then Sir Wally opened the batting.

‘I see from the press,’ he said, ‘that the Henderson Report comes down clearly on our side.’

I think perhaps he still thinks that I’m on his side. No, surely Humphrey must have briefed him. So he’s pretending that he thinks that I’m still on his side.

I was non-committal. ‘Yes, I saw that too.’

And I stared penetratingly at Humphrey.

He shifted uncomfortably in his seat. ‘Yes, that committee is leaking like a sieve,’ he said. I continued staring at him, but made no reply. There’s no doubt that he’s the guilty man. He continued, brazenly: ‘So Minister, there’s no real case for refusing permission for the new Plant now, is there?’

I remained non-committal. ‘I don’t know.’

Sir Wally spoke up. ‘Look, Jim. We’ve been working away at this contract for two years. It’s very important to us. I’m chairman and I’m responsible – and I tell you, as a chemist myself, that metadioxin is utterly safe.’

‘Why do you experts always think you are right?’ I enquired coldly.

‘Why do you think,’ countered Sir Wally emotionally, ‘that the more inexpert you are, the more likely

you

are to be right?’

you

are to be right?’

I’m not an expert. I’ve never claimed to be an expert. I said so. ‘Ministers are not experts. Ministers are put in charge precisely because they know nothing . . .’

‘You admit that?’ interrupted Sir Wally with glee. I suppose I walked right into that.

I persevered. ‘Ministers know nothing

about technical problems

. A Minister’s job is to consider the wider interests of the nation and, for that reason, I cannot commit myself yet.’

about technical problems

. A Minister’s job is to consider the wider interests of the nation and, for that reason, I cannot commit myself yet.’

Other books

The Doors Open by Michael Gilbert

The Shadow and Night by Chris Walley

A Corisi Christmas (Legacy Collection #7) by Ruth Cardello

What happened in Vegas: Didn't Stay In Vegas! by R. Lorelei

Big Fat Liar 3 (Big Fat Liar #3) by Cookie Moretti

Halon-Seven by Xander Weaver

The Revenant of Thraxton Hall: The Paranormal Casebooks of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle by Entwistle, Vaughn

DRAWN by Marian Tee

Secrets Gone South (Crimson Romance) by Pace, Alicia Hunter

Rojas: Las mujeres republicanas en la Guerra Civil by Mary Nash