The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (36 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

Â

All in the Family: The Julio-Claudian Emperors

In This Chapter

- The Julio-Claudian dynasty and the development of the principate

- Tiberius, stepson of Augustus

- Gaius (Caligula), the megalomaniac “Little Boots”

- Claudiusâhalf-wit or clever emperor?

- Nero, the flamboyant showman burned by his own self-aggrandizement

After the death of Augustus in

C

.

E

. 14, the first Roman emperors of the emerging Empire belonged to two hereditary dynasties. The first was Augustus's own family; the second came to power in the chaos that followed the death of Nero.

In this chapter, we'll follow the careers of the Julio-Claudians, who are the most famous (and infamous) emperors of the time. Besides their larger-than-life personalities, we'll see how the imperial family, staff, and personal bodyguard of the emperor (the Praetorian Guard) became more powerful and influential than the senate.

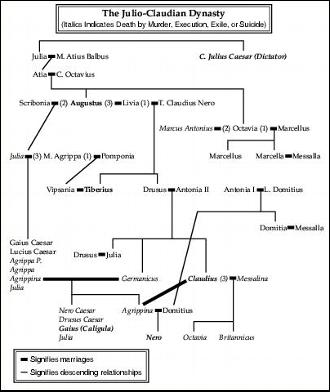

As you can see from the accompanying chart of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (the thing that looks roughly like a schematic for a circuit board), Augustus's tenacious attempts to ensure that a Julian would inherit his position created a tangled web of marriages, divorces, adoptions, and sour grapes that would make any soap opera producer proud. You have to admit that it was successful in that, of the first four emperors (Tiberius, Gaius, Claudius, and Nero), only Tiberius had no Julio in his Claudian. But if Augustus could have seen what kind of rivalries, not to mention what kinds of emperors, came of his efforts (in Gaius and Nero), he may have rethought his strategy.

The tortuous Julio-Claudian dynasty.

C

.

E

. 14â37)

Tiberius was proud, dour, and embittered by Augustus's treatment of him and by his marriage to Julia in 12

B

.

C

.

E

. He did what was asked of him well, but probably would rather have pursued other things. Passed over most of his life for younger Julians and forced to divorce his wife and marry Julia as a caretaker, he had retired to Rhodes and was later yanked back to Rome when young Julians kept dropping like flies. By Augustus's death, he was 56, a well-trained general and administrator, and obviously the heir apparent. He already shared Augustus's

imperium

and tribunician powers. The transition went smoothly.

In many respects, Tiberius was a success as an emperor. He was an experienced and efficient administrator, and judicious with foreign policy. He consolidated Augustus's borders, firmed up the frontier with Germany, and stabilized the eastern Empire mostly through diplomacy with the Parthians. In all the provinces, he worked at

financial and tax reform, instituted the building of roads and other public works, and appointed (mostly) qualified governors. He also encouraged provincials to communicate directly with the emperor when they felt that the governors were not handling things properly. Economically, the Empire went through a boom, and Tiberius was able to reduce taxes and still leave Rome 20 times better off than he had found it.

But to turn a campaign phrase, “it's not just the economy, stupid.” Tiberius's principate was marred by personality conflicts with the senate, suspicions of imperial intrigue, and struggles within his administration to become the next

princeps.

Tiberius's primary conflicts within the family came from his popular and volatile nephew, Germanicus, and his popular, volatile, and ambitious wife, Agrippina the Elder.

Â

Veto!

Our sources for the early Roman emperors are biased against them. The historians Dio, Suetonius, and Tacitus all belonged to a class of senators who had good reason to resent the growth of imperial power. These writers tended to favor (or even foster) dark, scandalous, and scurrilous explanations and reports over others.

Germanicus was a good commander but a loose cannon, prone to overstepping his bounds at the prospect of a great war for the glory of Rome (and the glory of Germanicus). Tiberius sent him to fight Arminius (who defeated Varus) in Germany. Although he was largely successful, he was also reckless. Tiberius recalled him from Germany and sent him to the east, where he again overstepped himself against the Parthians and in Egypt (the

princeps

's personal province). Tiberius suspected that Germanicus and Agrippina were attempting to build popular support against him and moved against Germanicus in the senate.

Germanicus also came into conflict with Piso, Tiberius's governor of Syria. Piso refused to recognize Germanicus's authority, and Germanicus ordered the uncooperative Piso to go home. Then Germanicus took mysteriously ill. As he died, he accused Piso of using sorcery and poison against him and called for vengeance. Piso later committed suicide. This set up a simmering public and private confrontation between the

princeps

and his mother, Livia, and Agrippina and her supporters in the senate, who suspected (or encouraged the suspicion) that Piso and Tiberius had been behind Germanicus's death.

Tiberius's relations with the senate were uncomfortable and frustrating. It was, in the words of today's human resources personnel, a bad fit. He disliked pretense and lacked Augustus's diplomacy. He tried to make the senate a partner in managing the state and

encouraged senators to speak their minds. Nevertheless, his proud nature and surly mannerisms were ill suited to inspiring confidence in how open he really was.

Â

When in Rome

Maiestas,

or prosecutable treason, came to include, by Julius Caesar's time, affronts to the dignity of the state. This law could become a capricious and dangerous political weapon in the hands of emperors (who were the state) and in the hands of unscrupulous accusers called delatores.

Â

Roamin' the Romans

When in Italy, you can visit the hauntingly beautiful remains of Tiberius's Villa Jovis, the best preserved of his 12 villas on the island of Capri. This remote and secluded site says a lot about Tiberius's need for privacy, study, and his desire to remain apart from the pretentious and contentious role into which he had been thrust as Augustus's eventual heir.

The more Tiberius pushed, the more senators balked. All knew that the

princeps

possessed the ultimate power and, eventually, that accusations of

maiestas

(real or contrived) could come against them. A senator once asked, “Would you please tell me when you're going to vote? If you go first I'll have an example to follow; if you go last I'm afraid that I might accidentally disagree with you.” This reality led to Tiberius's increasing distaste for the senate (whom he once called “men too ready to serve”) and the politics of Rome. He eventually withdrew from Rome to Capri, where he governed from afar and, for a time, through his prefect, Sejanus.

Lucius Aelius Sejanus rose to power as Prefect (commander) of the Praetorian Guard, a position that became powerful and influential. Sejanus “protected” the

princeps

's interests, and convinced Tiberius to remove himself from the increasingly dangerous capital to Capri.

Sejanus was, however, scheming for himself. Gradually Sejanus's powers were increased, and he virtually ruled Rome through power and prosecution while keeping Tiberius largely in the dark. He battled Agrippina's faction and married into the imperial family. Only Caligula, whom Tiberius had named as an heir, stood between him and the principate. There was a plot, and here something went very wrong for Sejanus. Antonia the Younger, Gaius's grandmother, sent a secret envoy on a mission to Tiberius and was able to reach him. Gaius was whisked to safety with Tiberius at Capri.

Tiberius turned on Sejanus in a way that was fitting for a student of Greek tragedy and rhetoric. He sent a carefully guarded letter to the senate. The letter first praised Sejanus, then expressed reservations, moved to accusations, and ended in a scathing condemnation

and call for execution. The senate complied, and by nightfall, a mob had brutally and gleefully dispatched Sejanus, his family, and their supporters.

After Sejanus, Tiberius was determined to root out the conspiracy that he thought might have extended even beyond Sejanus. He continued to rule from the seclusion of Capri until 37, when the dying

princeps

attempted to return to Rome, probably, as a last act, to arrange for a successor other than Caligula. He fell into a coma on the way. He is said to have revived temporarily, but Sejanus's successor Macro (who had had already nominated Caligula at Rome as the succeeding

princeps

) came and smothered Tiberius with his own bedding.