The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (22 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

Still, it's clear that Roman women, from early on, exercised influence and were visible in ways that many other cultures would have considered unthinkable. Tradition featured heroines who were active and influential (within Roman sensibilities), not just passive and submissive, and women who were important to the state and community, not just to the household and their husband. A part of these attitudes may have come to Rome through the influence of Etruscan culture, in which women (at least those of the aristocracy) appear to have had a status accorded elsewhere only to men.

Additional elements that came to be important in maintaining a degree of female independence were Roman laws and customs on marriage and divorce. While divorce doesn't appear early on, one form of Roman marriage (

sine manu

) listed in the Twelve Tables (450

B

.

C

.

E

.) permitted the woman to remain free of her husband's possession if she remained away from his house for three nights per year. She was, however, still under the

potestas

of her father. This form of marriage became extremely common in the later Republic and was the subject of criticism by social conservatives and those who thought that family values needed strengthening by making marriages more binding (on women). Under Augustus, a woman gained her legal independence if she had produced three children (or produced a document saying she had).

After Rome conquered the Mediterranean, some Roman aristocrats began to give their daughters a higher degree of education. The influx of wealth into Italy and the lengthy absences of men on military campaigns helped to create a class of women who exercised power and a degree of freedom and independence. The mothers, daughters, and wives of nearly all the influential and important Roman men of the last century of the Republic were active, educated, and influential. These women influenced public policy through their association with leading figures and, occasionally, through direct public action and demonstration. A remarkable example is Hortensia, the daughter of the famous Roman orator Hortentius. In 42

B

.

C

.

E

., in opposition to a tax imposed on wealthy women, Hortensia broke precedent when she mounted the Rostra in the Forum, delivered an oration on a matter of public policy, and won her point. She was, however, the first and last to do this.

Girls were married early (at about 14 to 15 years old) and often to a much older man. Ideally, the wife was to remain faithful, work hard for the family, teach children their virtues, and produce sons. Such a woman, given that she married initially to an older man and soldier, might have spent a good deal of the time as head of her household while her husband was away fighting and might have been widowed once or twice.

Among the upper classes, divorce became fairly common in the late Republic as marriages became a part of political and social networking. During this time, upper-class Roman women began to display a great deal more sexual freedom. Concerns about morality and declining birthrates brought legislation that attempted to restrict what women could wear in public and exacted penalties for adultery, being single, and being childless. Like most moralistic legislation passed by people who have the privilege of moral hypocrisy, it failed to have an effect.

The Romans' picture of themselves was firmly rooted in the ideal of a small rural community. Rome was the “town” to which the small farmers went to trade and to conduct public business. Wealthy families might live in the city most of the time where the

pater familias

and other men conducted business and politics; their land holdings were worked by slaves and tenement farmers, and they visited these holdings from time to time.

As Rome grew, the Romans became progressively urbanized and the city became increasingly the center of power. Land ownership consolidated as Roman farmers lost their land to debts and taxes during the campaigns against Carthage or conquests abroad. The soldiers and dispossessed migrated to the cities, where a vast urban proletariat became a restless and hungry force to be reckoned with by politicians.

Nevertheless, the Roman psyche remained essentially rural complete with a deep suspicion of the city slicker, the foreigner, and the itinerant worker (unskilled or professional). The picture of the small farmer working a piece of land in the country continued to be promoted and idealized by poets and public policy well past its time.

Roman religion had several layers. The Romans had family practices and beliefs that originated from time immemorial and community practices that were shared by the peoples of Italy. They also, at another level, adopted customs and beliefs from other influential cultures such as the Etruscans and the Greeks. As Rome grew, some foreign cults found a home as well. Finally, there was Roman state religious practice, which developed to encompass all these and to represent Rome as a whole.

That “Old Time” Religion

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Boundaries and thresholds have always held a special place in beliefs and rituals. The traditional practice of carrying the bride over the threshold comes from the Roman wedding ceremony. The bride smeared Janus's threshold with wolf fat and was lifted over the threshold into her new community.

The oldest Roman religious practice persevered in the home and, like the household culture, influenced many aspects of Roman culture. The home itself and the land on which it depended were sacred spaces, and within this universe, gods and spirits existed for its benefit and protection. Every morning and evening the family, including slaves, gathered and the

pater familias

led prayers to these spirits and to the ancestors on the family's behalf.

If you started in the field and walked toward the house you passed through the family gods' various terrain. Coming through the fields you were in the domain of the Lares, guardian spirits of the home's fields and farm. As you entered the door, you passed Janus, a two-faced god who represented and guarded the entrance of the home. Inside, there were the Penates, household spirits who blessed and guarded the food and the home. When you reached the symbolic center of the houseâthe hearth that provided light, food, and warmthâyou reached the goddess Vesta. Vesta's hearth and sacred objects (a table, salt, cake) were tended by the women of the family. New additions to the family such as children and brides were presented to her for blessing and acceptance.

Ancestor worship was an important part of family tradition and religion. Roman ancestors were as much a part of the family as any living member, and their approval was sought just as members sought to live up to their example. Families kept busts (statue portraits) and death masks of illustrious members and paraded them at funerals and special ceremonies. Family oral traditions about their deeds, recounted at funerals, became an important source for the first Roman historians.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Just as the hierarchy of the household served as a model for Roman civic authority, its religious structure was projected onto the city and land of Rome. The gates of Janus, through which the ancient armies marched in and out, stood open at an entrance to the Forum. These gates were closed only in times of peace. At the center of the Forum was the Temple of Vesta, with its female attendants, which contained the sacred hearth-fire of Rome. Thus the larger community of Rome came in many ways to resemble the clannish families from which it developed.

The ancestors represented the line of the family

genius,

the spirit of the family that was present physically and symbolically in the

pater familias.

His

genius

was revered as a unique and distinguishing connection to the gods, to tradition, and to legitimacy. It was both his (that is, he wasn't “possessed” by some ancestral spirit) and yet passed to the next

pater familias

as a kind of guardian angel and guiding spirit. It appears that the

mater familias

had a similar spirit that was worshipped after deathâthe

iuno.

As Rome developed into a regional power, it also developed into a religious center. Etruscan and Italic gods were taken into the city and were later understood as rough equivalents with the Greek gods. The high god of Rome was Jove/Jupiter, who became the divine

pater familias:

the highest authority, bringer of victory, and guarantor of justice. Next were Mars, who became the guardian of Roman war and defense of the city, and Quirinus, a Roman/Sabine god without a Greek or Etruscan counterpart. Juno, the

mater familias

wife of Jove, became prominent as well. Gradually, a pantheon of gods and goddesses had official temples and sacrifices in the city.

Â

Roamin' the Romans

You'll find busts of Romans in museums all over the world. Their fondness for portrait sculpture went back to portraits and death masks of ancestors. In the late Republic, wealthy Romans began to have marble portraits done of themselves (many more frankly realistic than you might imagine paying for) and sculpture became big business. You could, for instance, have your head done and select from a variety of pre-made bodies to put it on!

A bust of a Roman matron from the Glyptotech in Munich, Germany.

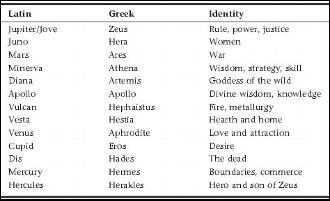

Here's a partial list of corresponding Latin and Greek gods:

Other than those, the Romans were quite suspicious of foreign religions, especially any that seemed emotional and charismatic. Even as Romans began to engage in foreign religious practices (especially in times of stress and uncertainty), officially Rome

was very much a NIMBY (not in my back yard) culture. The city did, in 205

B

.

C

.

E

., take in the “Great Mother” (

magna mater

) cult while in crisis and on orders from the Sibylline Oracles but didn't officially recognize another god until Julius Caesar. The senate forbade the worship of Bacchus in 186

B

.

C

.

E

. and periodically condemned followers of other religions and philosophies.

It wasn't that Rome believed its gods were exclusive (many Romans had stopped believing in the traditional state gods long before the end of the Republic); it was that foreign religions threatened stability and the nobility's lock on the power and influence of the traditional priesthood. Besides, they weren't

Roman.

Still, official warnings and decrees were to no avail: Romans practiced their family religions

and

others that they found appealing and fulfilling, such as the worship of the Egyptian goddess, Isis.

Â

Roamin' the Romans

When you visit Pompeii, you can see some of the household shrines, still beautifully preserved, around which Romans would have engaged in their family worship, as well as temples of Isis.