The Complete Essays (85 page)

Read The Complete Essays Online

Authors: Michel de Montaigne

Tags: #Essays, #Philosophy, #Literary Collections, #History & Surveys, #General

[C] The natives of Brazil are said to die only of old age; they attribute that to the serenity and tranquillity of the air: I would attribute it to the serenity and tranquillity of their souls; they are not burdened with intense emotions and unpleasant tasks and thoughts: they pass their lives in striking simplicity and ignorance. They have no literature, no laws, no kings and no religion of any kind.

126

[A] Experience shows that gross, uncouth men make more desirable and vigorous sexual partners; lying with a mule-driver is often more welcome than lying with a gentleman. How can we explain that except by assuming that emotions within the gentleman’s soul undermine the strength

of his body, break it down and exhaust it, [A1] just as they exhaust and harm the soul itself? Is it not true that the soul can be most readily thrown into mania and driven mad by its own quickness, sharpness and nimbleness – in short by the qualities which constitute its strength? [B] Does not the most subtle wisdom produce the most subtle madness? As great enmities are born of great friendships and fatal illnesses are born of radiant health, so too the most exquisite and delirious of manias are produced by the choicest and the most lively of the emotions which disturb the soul. It needs only a half turn of the peg to pass from one to the other. [A1] When men are demented their very actions show how appropriate madness is to the workings of our souls at their most vigorous. Is there anyone who does not know how imperceptible are the divisions separating madness from the spiritual alacrity of a soul set free or from actions arising from supreme and extraordinary virtue? Plato says that melancholics are the most teachable and the most sublime; yet none has a greater propensity towards madness. Spirits without number are undermined by their own force and subtlety. There is an Italian poet, fashioned in the atmosphere of the pure poetry of Antiquity, who showed more judgement and genius than any other Italian for many a long year; yet his agile and lively mind has overthrown him; the light has made him blind; his reason’s grasp was so precise and so intense that it has left him quite irrational; his quest for knowledge, eager and exacting, has led to his becoming like a dumb beast; his rare aptitude for the activities of the soul has left him with no activity… and with no soul. Ought he to be grateful to so murderous a mental agility? It was not so much compassion that I felt as anger when I saw him in so wretched a state, surviving himself, neglecting himself (and his works, which were published, unlicked and uncorrected; he had sight of this but no understanding).

127

Do you want a man who is sane, moderate, firmly based and reliable? Then array him in darkness, sluggishness and heaviness. [C] To teach us to be wise, make us stupid like beasts; to guide us you must blind us.

[A] If you say that the convenience of having our senses chilled and blunted when tasting evil pains must entail the consequential inconvenience of rendering us less keenly appreciative of the joys of good pleasures, I agree. But the wretchedness of our human condition means we have less to relish than to banish: the most extreme pleasures touch us less than the lightest of pains: [C]

‘Segnius homines bona quam mala sentiunt’

[Men feel

pleasure more dully than pain]. [A] We are far less aware of perfect health than of the slightest illness:

pungit

In cute vix summa violatum plagula corpus,

Quando valere nihil quemquam movet. Hoc juvat unum,

Quod me non torquet latus aut pes: caetera quisquam

Vix queat aut sanum sese, aut sentire valentem

.

[A man feels the slightest prick which scarcely breaks his skin; yet he remains unmoved by excellent health. Personally I feel delight in simply being free from pain in foot or side, while another scarcely realizes he is well and remains unaware of his good health.]

For us, being well means not being ill. So that philosophical school which sets the highest value on pleasure reduces it to the mere absence of pain. To be free from ill is the greatest good that Man can hope for. [C] As Ennius puts it,

Nimium boni est, cui nihil est mali

[Ample good consists in being free from ill].

128

[A] For even that tickling excitement which accompanies certain pleasures and which seems to exalt us above mere good health and freedom from pain, that shifting delight, active, inexplicably biting and sharp, aims in the end at freedom from pain. The appetite which enraptures us when we lie with women merely aims at banishing the pain brought on by the frenzy of our inflamed desires; all it seeks is rest and repose, free from the fever of passion.

The same applies to all other appetites. I maintain, therefore, that if ignorant simplicity can bring us to an absence of pain, then it brings us to a state which, given the human condition, is very blessedness.

[C] Yet we should not think of a simplicity so leaden as to be unable to taste anything. Crantor was right to attack ‘freedom from pain’ as conceived by Epicurus, insofar as it was built upon foundations so deep that pain could not even draw near to it or arise within it. I have no words of praise for a ‘freedom from pain’ which is neither possible nor desirable. I am pleased enough not to be ill but, if I am ill, I want to know; if you cut me open or cauterize me, I want to feel it. Truly, anyone who could uproot all knowledge of pain would equally eradicate all knowledge of pleasure and

finally destroy Man:

‘Istud nihil dolere, non sine magna mercede contingit immanitatis in animo, stuporis in corpore’

[That ‘freedom from pain’ has a high price: cruelty in the soul, insensate dullness in the body]. For Man, ill can be good at times; it is not always right to flee pain, not always right to chase after pleasure.

[A] It greatly advances the honour of Ignorance that Learning has to throw us into her arms when powerless to stiffen our backs against the weight of our ills; she has to make terms, slipping the reins and giving us leave to seek refuge in the lap of Ignorance, finding under her protection a shelter from the blows and outrages of Fortune.

Learning instructs us to [C] withdraw our thoughts from the ills which beset us now and to occupy them by recalling the good times we have known; [A] to make use of the memory of past joys in order to console ourselves for present sorrows, or to call in the help of vanished happiness to set against the things which oppress us now – [C]

‘Levationes aegritudinum in avocatione a cogitanda molestia et revocatione ad contemplandas voluptates ponit’

[He found a way to lessen sorrows by summoning thoughts away from troubles and calling them back to gaze on pleasure] – [A] when Learning runs out of force, she turns to cunning; when strength of arm and body fails, she resorts to conjuring tricks and nimble footwork; if that is not what is meant, what does it mean? When any reasonable man, let alone a philosopher, feels in reality a blazing thirst brought on by a burning fever, can you buy him off with memories of the delights of Greek wine? [B] That would only make a bad bargain worse.

Che ricordarsi il ben doppia la noia

.

[Recalling pleasure doubles pain.]

[A] Of a similar nature is that other counsel which Philosophy gives us: to keep only past pleasures in mind and to wipe off the sorrows we have known – as if we had the art of forgetfulness in our power. [C] Anyway, such advice makes us worse:

Suavis est laborum praeteritorum memoria

.

[Sweet is the memory of toils now past.]

[A] Philosophy ought to arm me with weapons to fight against Fortune; she should stiffen my resolve to trample human adversities underfoot; how has she grown so weak as to have me bolting into burrows with such

cowardly and stupid evasions? Memory reproduces what she wants, not what we choose. Indeed there is nothing which stamps anything so vividly on our memory as the desire not to remember it: the best way to impress anything on our souls and to make them stand guard over it, is to beg them to forget it.

– [C] The following is false:

‘Est situm in nobis, ut et adversa quasi perpetua oblivione obruamus, et secunda jucunde et suaviter meminerimus’

[There is within us a capacity for consigning misfortunes to total oblivion, while remembering favourable things with joy and delight].

The following is true:

‘Memini etiam quae nolo, oblivisci non possum quae volo’

[I remember things I do not want to remember and I cannot forget things I want to forget].

129

–

[A] Whose advice have I just cited? Why, that of the man [C]

‘qui se unus sapientem profiteri sit ausus’

[who, alone, dared to say he was wise];

[A] Qui

genus humanum ingenio superavit, et omnes

Praestrinxit Stellas, exortus uti aetherius sol

.

[who soared above human kind by his genius and who, like the Sun rising in heaven, obscured all the stars.]

Emptying and stripping memory is, surely, the true and proper road to ignorance. [C]

‘Iners malorum remedium ignorantia est’

[Ignorance is an artless remedy for our ills].

130

[A] We find several similar precepts permitting us, when strong and lively Reason cannot suffice, to borrow the trivial pretences of the vulgar, provided that they make us happy or provide consolation. Those who cannot cure a wound are pleased with palliatives which deaden it. If philosophers could only find a way of adding order and constancy to a life which was maintained in joy and tranquillity by weakness and sickness of judgement, they would be prepared to accept it. I do not think they will deny me that.

Potare et spargere flores

Incipiam, patiarque vel inconsultus haberi!

[I may appear silly, but I am going to start drinking and strewing flowers about!]

131

You would find several philosophers agreeing with Lycas: he was a man of very orderly habits, living quietly and peaceably at home; he failed in none of the duties he owed to family and strangers; he guarded himself effectively from harm; however, some defect in his senses led him to imprint a mad fantasy on his brain: he always thought he was in the theatre watching games, plays and the finest comedies in the world. Being cured of this corrupt humour, he nearly took his doctors to court to make them restore those sweet fantasies

132

to him:

pol! me occidistis, amici,

Non servastis, ait, cui sic extorta voluptas,

Et demptus per vim mentis gratissimus error

.

[‘You have killed me, my friends, not cured me,’ he said. ‘You have wrenched my pleasure from me and taken away by force that most delightful wandering of my mind.’]

Thrasilaus, son of Pythodorus, had a similar mad fantasy; he came to believe that all the ships sailing out of the port of Piraeus or coming in to dock there were working for him alone. When good fortune attended their voyages he rejoiced in it and welcomed them with delight. His brother Crito brought him to his senses, but he sorely missed his former condition, which had been full of happiness, not burdened by troubles.

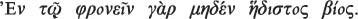

A line of Ancient Greek poetry says ‘There is great convenience in not being too wise’: So does Ecclesiastes: ‘In much wisdom there is much sadness, and he that acquireth knowledge acquireth worry and travail.’

So does Ecclesiastes: ‘In much wisdom there is much sadness, and he that acquireth knowledge acquireth worry and travail.’

Philosophy in general agrees

133

that there is an ultimate remedy to be prescribed for every kind of trouble: namely, ending our life if we find it intolerable. [C]

‘Placet? Pare. Non placet? Quacunque vis, exi.’

[All right? Then put up with it. Not all right? Then out you go, any way you like.] –

‘Pungit dolor? Vel fodiat sane. Si nudus es, da jugulum; sin tectus armis Vulcaniis, id est fortitudine, resiste.’

[Does it hurt? Is it excruciating? If you are defenceless, get your throat cut; if you are armed with the arms of

Vulcan (that is, fortitude) then fight it!] As the Greeks said at their banquets: ‘Let him drink or be off!’ (

‘Aut bibat, aut abeat!’

) – That is particularly apt if you pronounce Cicero’s language like. Gascon, changing your ‘B’s to ‘V’s:

Aut vivat-

‘Let him

live…’