The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Seven (35 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Seven Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

So square one is the basic ground from which we function, and square zero seems to be beyond even our functioning. Isness, without any definitions. It is not so much branching out, but branching in. There is still resistance to going back to zero, and it has always been a problem that square one could be the excuse for you not to have to go back to zero. At least you have the number one to clench on to; at least there’s that first number you made. You achieved your identity at square one, and that seems to be the problem. So ultimately, one has to return to zero. Then you begin to feel that you can move around. You can do a lot of things, not be numbered. You’re not subject to your own numbers, and you are not confined to a pigeonhole. So your situation could be improved if you know you have nothing but zero, which is nothing. There’s no reference point anymore, just zero. Try it. It is an expression of immense generosity and immense enlightenment.

Art Begins at Home

Dharma art is not purely about art and life alone. It has to do with how we handle ourselves altogether: how we hold a glass of water, how to put it down, how we can hold a note card and make it into a sacred scepter, how we can sit on a chair, how we can work with a table, how we do anything.

D

HARMA ART IS NOT

purely about art and life alone. It has to do with how we handle ourselves altogether: how we hold a glass of water, how to put it down, how we can hold a note card and make it into a sacred scepter, how we can sit on a chair, how we can work with a table, how we do anything. So it is not a narrow-minded approach or a crash course on how to be the best artist and get the best money out of that. I’m afraid it doesn’t work like that. Dharma art is a long-term project, but if you are willing to keep up with the basic discipline, you will never regret it. In fact, you will appreciate it a lot and you will be very moved at some point. Whenever you make your breakthrough and develop that reference point, you will appreciate it and enjoy it enormously. You will be so thankful. That is my personal experience. It has been done, and it will be done in the future.

Dharma art is a question of general awareness. It is much more than art alone. For instance, if you are involved with an art form, such as flower arranging, you could begin with your own household, organizing it in that fashion. You could set up a place for flower arrangements. In a Japanese household, there is always a place for a central arrangement, called a tokonoma. Or in the Buddhist tradition, there is always a shrine of some kind. Not only that, but you could work with the notion of how you arrange the kitchen, where you put your cups and saucers and where you put your pots and pans, how you put things away and arrange them properly. Also, in the bathroom, where you put your soap, where you put your towel; and in the bedroom, how you fold your sheets. You begin to come into your home with a sense that there is a total household, which takes hard work and discipline. At the same time, it is so elegant and practical that you don’t have to run into messy edges of any kind. That seems to be the start.

Once you have your domestic setup properly done, ideally you can invite a few friends to your house and show them how you handle your life. From that you can introduce flower arranging to people. In that way, flower arranging is not just something you do when you are feeling bad, like making a little flower thingy for your mantelpiece; it is a total world. Students should learn that; they should know that. You are not just making flower arrangements in your living room, but you have that same general sense of perception everywhere. So dharma art involves how to rinse your towel in the bathroom, how you hang it up properly so it dries nicely and you don’t have to iron it. It has to do with how your sheets are folded, how your table is placed in the sitting room. It is a total world, in which you pay attention to every little detail. If the executive director of IBM came to visit you, and you were fooling with these little things, he might think you were crazy—but on the other hand, he might appreciate you. This approach is not necessarily Oriental; it is just the basic sanity of how you do things properly and have a place for everything. It is running your household as a work of art. That seems to be the main point.

In this case, the particular arrangement of the household is not the duty of the husband or the wife or the children, but everybody does it. They each do their part, so nobody begins to be labeled as the housecleaner or the cook. Everybody in the family should learn how to cook, and they should also learn how to clean up after they have cooked. Everybody should learn how to make things clean and orderly. That way, eventually you won’t need a spring cleaning, as they say. Instead of once a year doing a whole big sweep, it’s being done every minute, every hour, every day. So everything is being handled properly and beautifully, and you begin to appreciate your home.

Even though you might be living in a plastic-looking condominium or apartment, you can still look elegant. That seems to be the basic point. It’s very natural. You don’t just throw things on the floor. When you take off your pajamas, you fold them up and put them in their proper place. Dharma art is natural awareness. You do not need to make a special effort or have a chunk of time in order to do a good job. It’s just a question of where you place your soap on your dish, how you fold your towel, which doesn’t take all that much extra time. That is dharma art, actually. We could experiment with that. Do you think it’s possible?

Sources

From the Author:

July 1974 letter.

Discovering Elegance:

Public Talk, Dharma Art, San Francisco, 1981.

Great Eastern Sun:

Talk 3, Visual Dharma Seminar, The Naropa Institute, 1978.

Basic Goodness:

Talk 4, Visual Dharma Seminar, The Naropa Institute, 1978.

Meditation:

Talk 1, Art in Everyday Life, Padma Jong, 1974. Talk 2, Dance of Enlightenment, Padma Jong, 1975.

Art in Everyday Life:

Talk 10, Vajradhatu Seminary, Jackson Hole, 1973.

Ordinary Truth:

Talk 1, Iconography of Buddhist Tantra, The Naropa Institute, 1975.

Empty Gap of Mind:

Talk 3, Iconography of Buddhist Tantra, The Naropa Institute, 1975.

Coloring Our World:

Talk 2, Iconography of Buddhist Tantra, The Naropa Institute, 1975.

New Sight:

Talks, Iconography of Buddhist Tantra, The Naropa Institute, 1975.

The Process of Perception:

Talk 6, Iconography of Buddhist Tantra, The Naropa Institute, 1975.

Being and Projecting:

Talk 4, Mudra Theater Intensive, Rocky Mountain Dharma Center, 1976.

Lost Horizons:

Talk 9, Iconography of Buddhist Tantra, The Naropa Institute, 1975.

Giving:

Talk 4, Iconography of Buddhist Tantra, The Naropa Institute, 1975.

Self-Existing Humor:

Talk 8, Iconography of Buddhist Tantra, The Naropa Institute, 1975.

Outrageousness:

Talks 2 and 3, Art in Everyday Life, Karmê Chöling, 1974.

Wise Fool:

Talk 10, Iconography of Buddhist Tantra, The Naropa Institute, 1975.

Five Styles of Creative Expression:

Milarepa Film Workshop, Karma Dzong, Boulder, 1972. Talk 2, Art in Everyday Life, Karmê Chöling, 1974. Chapter 9,

Journey without Goal

(Boston: Shambhala Publications, 1981).

Nobody’s World:

Talk 4, Mandala of the Five Buddha Families, Karmê Chöling, 1974.

Choiceless Magic:

Talk 7, Iconography of Buddhist Tantra, The Naropa Institute, 1975.

One Stroke:

Talk 6, Dance of Enlightenment, Padmajong, 1975.

The Activity of Nonaggression:

Talk 4, Dharma Art Seminar, The Naropa Institute, 1979. Talk 2, Dharma Art Seminar West, Los Angeles, 1980.

State of Mind:

Talk 1, Visual Dharma Seminar, The Naropa Institute, 1978.

Heaven, Earth, and Man:

Talk 2, Visual Dharma Seminar, The Naropa Institute, 1978.

Endless Richness:

Milarepa Film Workshop, Karma Dzong, Boulder, 1972.

Back to Square One:

Talks 1 and 2, Art in Everyday Life, Karmê Chöling, 1974.

Art Begins at Home:

Talk 3, Dharma Art Seminar West, Los Angeles, 1980.

T

HE

A

RT OF

C

ALLIGRAPHY

Joining Heaven and Earth

EDITED BY

J

UDITH

L. L

IEF

Introduction

D

AVID

I. R

OME

Venerating the past in itself will not solve the world’s problems. We need to find the link between our traditions and our present experience of life.

Nowness,

or the magic of the present moment, is what joins the wisdom of the past with the present. When you appreciate a painting or a piece of music or a work of literature, no matter when it was created, you appreciate it

now.

You experience the same now in which it was created. It is always

now.

C

HÖGYAM

T

RUNGPA

Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior

D

URING THE TWENTY-YEAR PERIOD

of his remarkable proclamation of Buddhist and Shambhala teachings in the West, brush calligraphy was a primary means of expression for Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. Through his practice of calligraphy, Trungpa Rinpoche captured the moment of

now

and gave it concrete expression in order that others, in other times and places, might also experience

now.

Trungpa Rinpoche emphasized what he called “art in everyday life.” As he explains at some length in the essay published in this book, this means that the attitude, insight, and skill one brings to creating a work of art are not different from the attitude, insight, and skill with which one approaches every aspect of life. The “sacred world” expressed through art is not in opposition to a profane world. Samsara and nirvana are nondual. This basic view, so different in its thrust from the mainstream of Western spiritual and artistic tradition, sees “Art” as part of a continuous spectrum that includes every kind of creativity in one’s life—even, as Rinpoche was fond of saying, how we brush our teeth and wear our clothes.

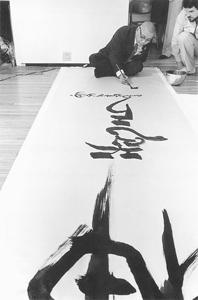

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche executing a calligraphy for a dharma art exhibit in Los Angeles, circa 1980.

PHOTOS BY ANDREA ROTH. FROM THE COLLECTION OF SHAMBHALA ARCHIVES.

While not separate from everyday life, art nonetheless represents a heightening of experience, what Trungpa Rinpoche refers to as “extending the mind through the sense perceptions.” It is the apprehension and the expression of what he calls “basic beauty,” beauty that transcends the dualities of beautiful versus ugly. Basic beauty is recognized and captured through the threefold dynamic of heaven, earth, and man. This ancient Oriental hierarchy of the cosmos, and of our experience of it, forms the basis of Trungpa Rinpoche’s essay. Focusing in turn on artistic creation, the process of perception, and the discipline of artmaking, he explicates the heaven, earth, and man aspects of each.

The essential moment in both creation and perception, the moment when heaven and earth touch, is indicated by Trungpa Rinpoche’s hallmark phrase “first thought best thought.” Whether applied to art or to life in general, the import of this slogan is not so much that we should seize on the first thought or image that pops into our head; rather, it is to trust in a state of mind that is uncensored and unmanipulated. “It’s the vajrayana [tantric Buddhist] idea of . . . simplicity, no ego involved, just purely”—here Rinpoche pauses and gasps, then continues—“precise! Tchoo!”