The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One (23 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

A new seminary would need more ground and many other arrangements would have to be made. I discussed these plans with my secretary and though I asked various people for donations I said I would like to contribute the monastery’s share from my personal funds. People were not very enthusiastic, but because of my request they agreed to support the idea. We decided that after my next visit to Sechen, I would bring a khenpo back with me as a permanent head for the seminary.

Soon after this I returned to Sechen; this time Apho Karma, nine other monks, and my little brother, the nine-year-old incarnate Tamchö Tenphel, abbot of the small monastery of Kyere, came with me. At Sechen I was welcomed by my guru and many other friends, all of whom had doubted whether I would return. I found everyone in the monastery in a state of great turmoil. The reason was, so Jamgön Kongtrül told me, that they had received a letter from Khyentse Rinpoche saying that he had left the monastery of Dzongsar for good owing to the probability of the further spread of Chinese Communism; he intended to settle permanently in India and to make pilgrimages to all the holy places; he died later in Sikkim. Everyone was very upset at his departure and Jamgön Kongtrül thought it might be wise to leave as well. The whole atmosphere of Sechen was disturbed; finally the latter decided to stay on for at least a few more years.

It gave me great comfort that I could continue my studies, for I was now better able to understand and appreciate the teaching; I realized that soon I might have no one to teach me, so the privilege of being in contact with my guru was of greater importance than ever. During the summer vacation I studied with redoubled zest under my great teacher and all but completed my lessons in meditation as well as the course of philosophic studies. My guru told me that I should learn further from his disciple Khenpo Gangshar, one of the six senior professors at Sechen, who was not only immensely learned but was also very advanced spiritually. I thought this meant that I should invite Khenpo Gangshar to help us at the new seminary; but though the friendship between the two monasteries was very close, all this would have to be discussed with the abbots and the monastic committee of Sechen in consultation with Jamgön Kongtrül. With great kindness they finally agreed to let Khenpo Gangshar come to my monastery for an unspecified time. I wanted him to come as soon as possible and it was agreed that he would make the journey in six months’ time. This meant, of course, that I could not stay at Sechen much longer. Though my own training in meditation had been completed under Jamgön Kongtrül, I still had to qualify as an instructor in this spiritual art, besides finishing my theoretical studies.

The Sechen authorities asked me to attend the summer celebration of Guru Padmakara’s birthday, and this I could not refuse since I expected it would be for the last time. The services would last for ten days under Tulku Rabjam Rinpoche, and Jamgön Kongtrül would also occasionally attend them.

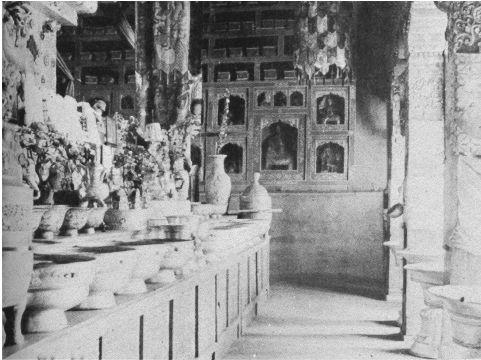

The assembly hall at Sechen was very large and dimly lit. The gold on the wonderful wall paintings and hangings reflected the light of the lamps against the red-lacquered pillars and, following the Mindröling tradition, a particularly fragrant incense was used, which permeated everywhere. The objects on the shrine were extremely delicate and beautifully arranged, and the carved butter ornaments for the sacrificial cakes were real works of art.

On the tenth day of the celebration a religious dance was held: Its theme was the eight aspects of Guru Padmakara, and there were other dances connected with the “wrathful” aspect of the Buddhamandala; these dances were performed by some three hundred monks. The costumes were very old and decorative and thousands of people came to watch. This was the only anniversary at which women were allowed within the precincts of the monastery and they greatly enjoyed this opportunity to visit the beautiful shrines. We ended with a

marme mönlam

(prayer with lamps) and all prayed that we might be eternally united in the dharma.

Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche

.

Khyentse Rinpoche of Dzongsar

.

A shrine room

.

PHOTO: PAUL POPPER, LTD.

As I soon had to leave Sechen, my last three weeks were spent with Jamgön Kongtrül Rinpoche at his residence. He gave me his final instructions, saying, “You have now learned a great deal from me, but you must improve your knowledge. Much comes from one’s own experience in teaching, reading, and contemplating. A teacher must not refuse to help others; at the same time he can always learn. This is the way of the bodhisattvas, who while they helped others, gained further enlightenment themselves. One must be wholely aware of all that one does; for in teaching, however expertly, if one’s own understanding be insufficient, there is danger of simply using words regardless of their spiritual meaning; therefore you must still remember that you yourself will continue to be a pupil on the way.”

A memorable farewell dinner was given for me by the monastic committee of Sechen, for though, fundamentally, the monastery belonged to the Nyingma school, there was a close affiliation to the Kagyü. Jamgön Kongtrül was both a teacher and a learner of many schools and particularly of the Kagyü, and in this he followed the example of his previous incarnation. In such an atmosphere our vision was greatly enlarged. When I left this friendly and all-embracing society I felt a slightly narrower life was closing round me; though within my monastery, as with its neighbors, religious study and meditation were continuously practiced, fewer monks came from other schools. Everything seemed to have slowed down, especially at Dütsi Tel since the death of the tenth Trungpa Tulku Rinpoche, and I was hoping to revive this spirit of expansion and development. It was a great consolation to me that Khenpo Gangshar had promised to come and help us. However, at Namgyal Tse there had been some progress; its seminary was attracting scholars from many different schools.

Akong Tulku came away with me, though he wanted to study further at Sechen. On our journey we met many monks carrying their books on the tops of their packs; their first exchange was always “What philosophy have you studied, what courses of meditation, under what teacher, and at what monastery?” for the monasteries in that area were in a very flourishing state with constant exchange of people seeking instruction in various spiritual techniques; there were laymen also engaged on similar pilgrimages.

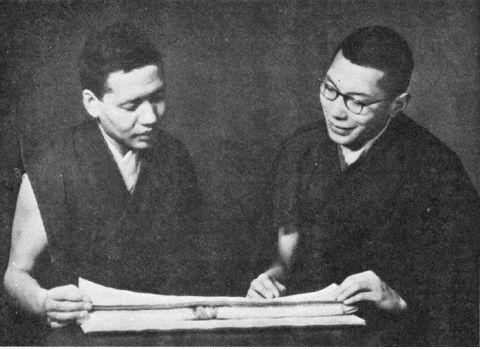

The author

(right)

with Akong Tulku

.

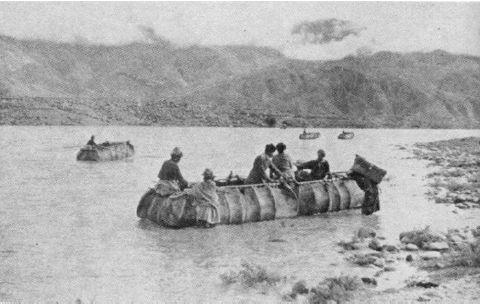

Yak-skin coracles on the Tsangpo River

.

PHOTO: PAUL POPPER, LTD.

It was now apparent that the Communists were becoming more officious; they now checked all travelers, and we were told that they sometimes made arrests, though we were not actually molested.

On reaching Surmang I received an invitation to visit China, and the Communists also wanted me to join the central committee of their party. Since my secretary was already a committee member, I said it would be unnecessary for me to join as well, but should he be prevented from attending the meetings, I would take his place. Moreover as he was the more experienced man, he would be of greater use to them and he could speak on our behalf. This could not be objected to, though my monks realized that the Chinese, if their demands were not complied with, would certainly take further steps to get me in their power.

Khampas in Revolt

H

IS

H

OLINESS

the Dalai Lama had visited India in November 1956 for the Buddha Jayanti celebrations held every hundred years in memory of the Buddha’s enlightenment and had returned to Lhasa the following February. While away, he had met Buddhists from all parts of the world and we now hoped that, with this publicity, he would be able to improve conditions for the rest of us, so our thoughts and devotions concentrated on this hope. Each New Year the festival of tsokchen was held at Surmang, and religious dancing took place for three days from sunrise to sunset; on the fourth day this went on for twenty-four hours with hardly a break. This was the first time that I had been able to take part in it. I looked forward to doing so and practiced hard, so instead of being utterly exhausted, as I had expected, I did not feel it too great a strain. I found that dancing, when combined properly with meditation, fills one with strength and joy.

Soon after the festival we sent monks and transport to Sechen to fetch Khenpo Gangshar who was to be my private tutor as well as director of the seminary. Apho Karma had already said that he wanted to retire as he was growing old and feeling very tired. He thought that he had taught me all he could, and was now more my attendant than my tutor. I asked him to remain as a member of my household and as my close adviser; he had been with me for so long and was almost a father to me. But he said that even as an adviser, the work was too much for him. He wanted to go back to meditate at the hermitage where he had once lived for three years behind bricked-in doors, receiving food through a panel, so it was arranged that he should leave me. This parting was a great grief to me, but it left me freer to make my own decisions without asking for outside advice.