The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One (15 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

At the time when Trungpa Tulku made the last-moment decision to go to his guru, he and his monks were encamped beside a river and he knew if he could but get away and cross it, then Palpung Monastery lay some ten days’ journey further on. He made a plan and confided part of it to his special friend Yange: He told him that he would give the monks a great treat, a picnic by the riverbank; they were to have a plentiful supply of food and tea, and the customary discipline of not talking after proscribed hours would be relaxed. That evening Yange was to prepare a bag of roast barley flour (tsampa) and leave it with his horse, which must be ready saddled, behind some nearby bushes. At this, Yange was much alarmed, for he realized that he was planning to escape.

The monks thoroughly enjoyed the picnic, especially the relaxation of the rule of silence, and they chatted on till the small hours of the morning, when drowsiness overtook them. Seeing this, Trungpa Tulku stole away, mounted his horse, and put it at the river which was in spate as the snow was thawing. He was ready to drown rather than miss the opportunity of training under the guru who meant so much to him. The horse managed to breast the current and on reaching the farther side the abbot decided to continue on foot, since riding implies a desire for power and for material possessions, so he tore off a piece of his robe and tied it to his horse’s back, as the customary sign that it had been ceremonially freed by a lama and must not be ill-treated by whoever caught it. He then set the horse free and walked on. The horse recrossed the river and returned to the camp, but the flapping of the piece of robe made it restive, and approaching one of the tents it rubbed against it to get rid of this annoyance and in doing so knocked down the tent. This awoke the sleepers who, seeing the horse, thought it must have broken from its tether. However, when they saw it was saddled and that the saddle was one used by their abbot, they were extremely disturbed and went to Trungpa Tulku’s tent. It was empty, and some of his clothes were arranged to look like a sleeping figure in the bed. Rushing out, they woke up the entire camp. All the monks examined the horse and found that it was wet; they also recognized the robe, and were forced to the conclusion that their abbot had left them and crossed the river.

Since Trungpa Tulku was quite unused to walking, they thought that he would soon be in difficulties and that they must look for him, so they split up in four groups to search up and down both banks of the river. The group who were going in the southerly direction on the further bank found a saddle rug which had belonged to the abbot, but beyond this there were no more traces. As a matter of fact, Trungpa Tulku had purposely dropped it there to mislead them.

Traveling northward, he was all but overwhelmed by a sense of utter desolation; never before had he been all alone, having always been surrounded by monks to attend and guard him. He walked fast until he was exhausted and then lay down to sleep. The sound of the rushing river and of dogs barking in a distant village seemed to him like a death knell; this was such a complete change from his very ordered life.

He was now on the same road that he had taken with his party on their outward journey; then he had talked and questioned many of the local people about the general lie of the land and what track led to Palpung Monastery, and now as soon as dawn broke he walked on and arrived early in the morning at the house of a wealthy landowner whom he had visited on the way through. The husband opened the door at his knock, but failed to recognize the visitor; however, since he was in monk’s robes he invited him to come in. When his wife appeared she gave a cry of surprise, for she immediately realized who it was, and her surprise was all the greater at seeing him alone. Trungpa Tulku asked them to shelter him and made them promise not to tell anyone of his whereabouts, since the reason for his being there was a great spiritual need. They were very frightened, but felt obliged to obey their abbot, so they gave him food and hid him in a large store cupboard, where he remained all that day, and when some of the searching monks came to the house to ask if he had been seen, the landowner and his wife kept to their promise.

In the evening Trungpa Tulku said that he must move on. His hosts were extremely upset that he should go on foot and unattended. They begged him to tell them what had occurred and wanted to know if there had been any misunderstanding between him and his bursar. They suggested, if this had been the case, that perhaps they could arrange for the matter to be cleared up, for their family was in a position to use its influence. Trungpa Rinpoche told them that he did not wish this, and with the greatest reluctance they let him leave, knowing that, as their abbot, it was his place to command and theirs to obey.

As he was making his way beside the river, he heard horses close behind him, so he hid in some bushes on the bank and the riders passed by. They proved to be the bursar with a mounted party; after a short interval he was able to resume his walk and in the early morning reached another house where he was known. But by now the bursar had alerted the whole neighborhood, so the family was informed of the situation; nevertheless, they took him in and offered to look after him, again hiding him in a store cupboard. As for the bursar, when he could find no further footmarks, he told the monks to search every house in the district. He was dissatisfied with the answers to his inquiries from the family with whom Trungpa Tulku was sheltering and ordered the monks to look in every nook and corner which they did; they found him in the cupboard where he was still hiding.

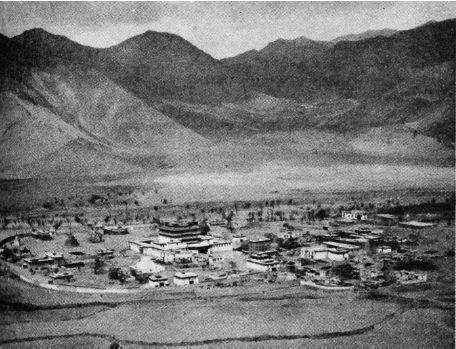

Samye, the first monastic institution in Tibet

.

The bursar embraced him with tears in his eyes and asked why he was causing them so much anxiety. He replied that he had private reasons with which no one might interfere. They argued all day, but the abbot gave no indication of his plans, though he refused to return to Surmang. Whereupon the bursar sent back for instructions from Namgyal Tse, and Dütsi Tel, from which, however, no reply could be expected for ten days or so.

When the message was received at Surmang, a meeting was called of all the heads of the monasteries and the representatives of the laity to discuss the matter; all agreed that their abbot must be requested to return. On receiving this reply the bursar endeavored to persuade Trungpa Tulku to follow the wishes of his people, but from being a very gentle and docile man, he now seemed to have become very strong-willed and obstinate. Another messenger was sent to Surmang to tell them that in spite of their requests the abbot would not change his mind.

After a second meeting had been called it was decided that if Trungpa Tulku could not be persuaded to come back, he should be allowed to go on his way, but with some monks and horses to serve him. When the messenger returned with this ultimatum, Trungpa Tulku was really upset, and even more so when a party of monks with horses arrived shortly afterward. He protested against all this fuss, saying that he was a simple man whose object in running away had been to escape from this complicated way of living.

His bursar and monks never ceased to argue with him, but instead of replying he preached to them on the vanity of leading a worldly life. A deadlock was reached when he said that to go with attendants and horses would ruin all that he wished to do. There is a Tibetan saying: “To kill a fish and give it to a starving dog has no virtue.” The Buddha left his kingdom, fasted, and endured hardships in order to win enlightenment, and many saints and bodhisattvas had sacrificed their lives to follow the path of dharma.

Finally, the bursar, who was an old man, broke down and wept. He told Trungpa that he must take at least two monks to look after him, while the baggage could be carried on a mule. This advice, coming from so senior a monk who was also his uncle, he reluctantly agreed to accept and they started on their journey; the bursar insisted on accompanying the party. Traveling on foot was very tiring, but to everyone’s surprise Trungpa seemed to acquire new strength and when the others were worn out, it was he who looked after them. The elderly bursar became ill with exhaustion, in spite of which, he said he really felt much happier, for the more he pondered on the teaching about the difference between the material and the spiritual way of life, the more he realized how right Trungpa Tulku was to follow this path.

Jamgön Kongtrül of Sechen

.

Infant Tai Situ of Palpung

.

Third incarnation of Jamgön Kongtrül of Palpung

.

Khenpo Gangshar

.

After ten days they reached Palpung Monastery, which was the second in importance of the Karma Kagyü school. Trungpa Tulku was already well known to many of the monks, but since he did not wish to be recognized they went on at once to Jamgön Kongtrül’s residence some three miles beyond.

Jamgön Kongtrül himself had had a premonition the day before, saying that he was expecting an important guest and that the guest room must be made ready. The monks thought he was referring to some royal personage with his attendants, or possibly to some great lama, and they eagerly watched for his arrival; however, no one appeared until late in the afternoon when four simple pilgrims with a single mule walked toward them and asked for accommodation. The monks told the travelers that, since an important visitor was already expected, the guest house adjoining Jamgön Kongtrül’s residence was not free, therefore the travelers must find a lodging wherever they could.