The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight (24 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

Of course, if you are starving, then what you want is food. In fact, food is what you need. But the genuine desires of those who are in need can be ruthlessly manipulated. War based on grasping has happened over and over again in this world. People with money have been willing to sacrifice thousands of human lives to hold on to their wealth, and on the other side, people in need have been willing to massacre their fellows for a grain of rice, a hope for a penny in their pocket.

Mahatma Gandhi asked the Indian people to embrace nonviolence and to renounce clinging to foreign ways, which they associated with wealth and prosperity. Since most Indians wore cloth that was British-made, he asked them to give up wearing British cloth and weave their own. This proclamation of self-sufficiency was one way, and a powerful one, of promoting dignity based, not on material possessions, but on one’s inherent state of being. But at the same time, with every respect for Gandhi’s vision of nonaggression, which he called

satyagraha,

or “seizing the truth,” we should not confuse his message with extreme asceticism. In order to find one’s inherent wealth, it is not necessary to renounce all material possessions and worldly pursuits. If a society is to have a sense of command and being ruled, then someone has to wear the three-piece suit at the negotiating tables; someone has to wear a uniform to keep the peace.

The basic message of the Shambhala teachings is that the best of human life can be realized under ordinary circumstances. That is the basic wisdom of Shambhala: that in this world, as it is, we can find a good and meaningful human life that will also serve others. That is our true richness. At a time when the world faces the threat of nuclear destruction and the reality of mass starvation and poverty, ruling our lives means committing ourselves to live in this world as ordinary but fully human beings. The image of the warrior in the world is indeed, precisely, this.

In a practical sense, how can we bring the sense of richness and ruling into our ordinary lives? When the warrior has achieved a certain mentality, having understood the basic principles of dignity and gentleness thoroughly, as well as having an appreciation for the drala principle and the principles of lha, nyen, and lu, then he or she should reflect on the general sense of wealth or richness in his or her life. The basic practice of richness is learning to project the goodness that exists in your being, so that a sense of goodness shines out. That goodness can be reflected in the way your hair is combed, the way your suit fits, the way your living room looks—in whatever there is in your immediate world. Then it is possible to go further and experience greater richness by developing what are called the seven riches of the universal monarch. These are very ancient categories first used in India to describe the qualities of a ruler. In this case, we are talking about developing these qualities individually, personally.

The first richness of the ruler is to have a queen. The queen—or we could say wife or husband, if you like—represents the principle of decency in your household. When you live with someone with whom you can share your life, both your wisdom and your negativities, it encourages you to open up your personality. You don’t bottle things up. However, a Shambhala person does not have to be married. There is always room for bachelors. Bachelors are friends to themselves as well as having a circle of friends. The basic principle is to develop decency and reasonability in your relationships.

The second richness of the universal monarch is the minister. The principle of the minister is having a counselor. You have your spouse who promotes your decency, and then you have friends who provide counsel and advice. It is said that the ministers should be inscrutable. The sense of inscrutability here is not that your friends are devious or difficult to figure out but that they do not have a project or goal in mind that clouds their friendship with you. Their advice or help is open-ended.

The third richness is the general, who represents fearlessness and protection. The general is also a friend, a friend who is fearless because he or she has no resistance to protecting you and helping you out, doing whatever is needed in a situation. The general is a friend who will actually care for you, as opposed to one who provides counsel.

The fourth richness is the steed, or horse. The steed represents industriousness, working hard and exerting yourself in situations. You don’t get trapped in laziness, but you constantly go forward and work with situations in your life.

The fifth richness is the elephant, which represents steadiness. You are not swayed by the winds of deception or confusion. You are steady like an elephant. At the same time, an elephant is not rooted like a tree trunk—it walks and moves. So you can walk and move forward with steadiness, as though riding an elephant.

The sixth richness of the ruler is the wish-granting jewel, which is connected with generosity. You don’t just hold on to the richness that you achieve by applying the previous principles, but you let go and give—by being hospitable, open, and humorous.

Number seven is the wheel. Traditionally, the ruler of the entire universe holds a gold wheel, while the monarch who rules this earth alone receives an iron wheel. The rulers of Shambhala are said to have held the iron wheel, because they ruled on this earth. On a personal level, the wheel represents command over your world. You take your seat properly and fully in your life, so that all of the previous principles can work together to promote richness and dignity in your life.

By applying these seven principles of richness, you can actually handle your family life properly. You have a wife or husband, which promotes decency; you have close friends, who are your advisers; and you have your guardians, or companions, who are fearless in loving you. Then you have exertion in your journey, in your work, which is represented by the horse. You ride on your energy all the time; you never give up on any of the problems in your life. But at the same time, you have to be earthy, steady, like an elephant. Then, having all those, you don’t just feel self-satisfied, but you become generous to others, like the wish-granting gem. Because of that, you rule your household completely; you hold the wheel of command. That is the vision of how to run your household in an enlightened fashion.

Having done that, you feel that your life is established properly and fully. You feel that a golden rain is continuously descending. It feels solid, simple, and straightforward. Then, you also have a feeling of gentleness and openness, as though an exquisite flower has bloomed auspiciously in your life. In whatever action you perform, whether accepting or rejecting, you begin to open yourself to the treasury of Shambhala wisdom. The point is that, when there is harmony, then there is also fundamental wealth. Although at that particular point you might be penniless, there is no problem. You are suddenly, eternally rich.

If you want to solve the world’s problems, you have to put your own household, your own individual life, in order first. That is somewhat of a paradox. People have a genuine desire to go beyond their individual, cramped lives to benefit the world. But if you do not start at home, then you have no hope of helping the world. So the first step in learning how to rule is learning to rule your household, your immediate world. There is no doubt that, if you do so, then the next step will come naturally. If you fail to do so, then your contribution to this world will be further chaos.

Part Three

AUTHENTIC PRESENCE

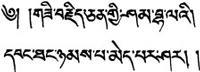

For the dignified Shambhala person,

An unwaning authentic presence dawns.

NINETEEN

The Universal Monarch

The challenge of warriorship is to step out of the cocoon, to step out into space, by being brave and at the same time gentle.

I

N PART TWO WE DISCUSSED

the possibility of discovering magic, or drala, and how that discovery can allow us to transform our existence into an expression of sacred world. Although, in some respects, all of these teachings are based on very simple and ordinary experiences, at the same time, you might feel somewhat overwhelmed by this perspective, as though you were surrounded by monumental wisdom. You still might have questions about how to go about actualizing the vision of warriorship.

Is it simply your personal will power and exertion which bring about the courage to follow the path of the Shambhala warriors? Or do you just imagine that you are seeing the Great Eastern Sun and hope for the best—that what you have seen is “it”? Neither of these will work. We have seen in the past that some people try to become warriors with an intense push. But the result is further confusion, and the person uncovers layer upon layer of cowardice and incompetence. If there is no sense of rejoicing and magical practice, you find yourself simply driving into the high wall of insanity.

The way of the warrior, how to be a warrior, is not a matter of making amateurish attempts, hoping that one day you will be a professional. There is a difference between imitating and emulating. In emulating warriorship, the student of warriorship goes through stages of disciplined training and constantly looks back and reexamines his own footprints or handiwork. Sometimes you find signs of development, and sometimes you find signs that you missed the point. Nevertheless, this is the only way to actualize the path of the warrior.

The fruition of the warrior’s path is the experience of primordial goodness, or the complete, unconditional nature of basic goodness. This experience is the same as the complete realization of egolessness, or the truth of non-reference point. The discovery of non-reference point, however, comes only from working with the reference points that exist in your life. By reference point here, we simply mean all of the conditions and situations that are part of your journey through life: washing your clothes, eating breakfast, lunch, and dinner, paying bills. Your week starts with Monday, and then you have Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. You get up at six

A.M.

and then the morning passes and you have noon, afternoon, evening, and night. You know what time to get up, what time to take a shower, what time to go to work, what time to eat dinner, and what time to lie down and go to sleep. Even a simple act like drinking a cup of tea contains many reference points. You pour yourself a cup of tea; you pick up a spoonful of sugar and bring it toward your teacup; you dip the spoon into the cup and stir it around so that the sugar becomes thoroughly mixed with the tea; you put the spoon down; you pick up the cup by its handle and bring it toward your mouth; you drink a little bit of tea and then you put the cup down. All of those processes are simple and ordinary reference points that show you how to conduct your journey through life.

Then you have reference points that are connected with how you express your emotions. You have love affairs, you have quarrels, and sometimes you get bored with life, so you read a newspaper or watch television. All of those emotional textures provide reference points in conducting your life.

The principles of warriorship are concerned, first of all, with learning to appreciate those processes, those mundane reference points. But then, by relating with the ordinary conditions of your life, you might make a shocking discovery. While drinking your cup of tea, you might discover that you are drinking tea in a vacuum. In fact,

you

are not even drinking the tea. The hollowness of space is drinking tea. So while doing any little ordinary thing, that reference point might bring an experience of non-reference point. When you put on your pants or your skirt, you might find that you are dressing up space. When you put on your makeup, you might discover that you are putting cosmetics on space. You are beautifying space, pure nothingness.

In the ordinary sense, we think of space as something vacant or dead. But in this case, space is a vast world that has capabilities of absorbing, acknowledging, and accommodating. You can put cosmetics on it, drink tea with it, eat cookies with it, polish your shoes in it. Something is there. But ironically, if you look into it, you can’t find anything. If you try to put your finger on it, you find that you don’t even have a finger to put! That is the primordial nature of basic goodness, and it is that nature which allows a human being to become a warrior, to become the warrior of all warriors.

The warrior, fundamentally, is someone who is not afraid of space. The coward lives in constant terror of space. When the coward is alone in the forest and doesn’t hear a sound, he thinks there is a ghost lurking somewhere. In the silence he begins to bring up all kinds of monsters and demons in his mind. The coward is afraid of darkness because he can’t see anything. He is afraid of silence because he can’t hear anything. Cowardice is turning the unconditional into a situation of fear by inventing reference points, or conditions, of all kinds. But for the warrior, unconditionality does not have to be conditioned or limited. It does not have to be qualified as either positive or negative, but it can just be neutral—as it is.