The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (92 page)

Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

In mid-April 1953, just as they were moving ahead on Little Switch and Panmunjom, the Chinese struck again, some twenty-three hundred of them, attacking the tiny garrison at Pork Chop. What ensued was a furious artillery battle. Slam Marshall, who wrote of that battle as he did of the fighting up near Kunuri, said that during the first day of the artillery barrage, the nine artillery battalions of the Second and Seventh divisions fired 37,655 rounds, and on the second day alone an additional 77,349 rounds. “Never at Verdun were guns worked at any rate such as this. The battle of Kwajalein, our most intense shoot during World War II, was still a lesser thing when measured in terms of artillery expenditure per hour, weight of metal against yards of earth and the grand output of the guns,” he wrote. “For this at least the operation deserves a place in history. It set the all time mark for artillery effort.”

The American troops managed to hold. In July 1953, the Chinese tried once again. The battle went on ferociously for two days, with both sides in a virtual stalemate on the crest of the hill. King Company, commanded by Lieutenant Joe Clemons, took the hardest hit. Clemons had gone up there with 135 men in his command and came back with 14. The fighting went back and forth over five days, from July 6 to July 11. On the morning of July 11, Maxwell Taylor drove up to Trudeau’s headquarters and told him that Pork Chop was not worth the investment of any more American lives, that the battle was over. The remaining American forces slipped off the hill, unbeknownst to the Chinese. When someone asked Major General Mike West, the commander of the British Commonwealth Division, what he would have done to get Pork Chop back, he answered, “Nothing. It was only an outpost.” Sixteen days later, on July 27, a truce began in Korea.

A difficult, draining, cruel war had ended under terms that no one was very happy with.

P

ERHAPS ALL WARS

are in some way or another the product of miscalculations. But Korea was a place where almost every key decision on both sides turned on a miscalculation. First, the Americans took Korea off their defensive perimeter, which in turn encouraged the varying Communist participants to act. Then, the Soviets gave a green light to Kim Il Sung to invade the South, convinced the Americans would not come in. When the Americans entered the war, they greatly underestimated the skills of the North Korean troops they were going to face, and vastly overestimated how well prepared the first American troops to go into battle were. Later, the Americans decided to drive north of the thirty-eighth parallel, paying no attention to Chinese warnings.

After that, in the single greatest American miscalculation of the war, MacArthur decided to go all the way to the Yalu because he was sure the Chinese would not come in, and so made his troops infinitely more vulnerable. Finally, Mao believed that the political purity and revolutionary spirit of his men greatly outweighed America’s superior weaponry (and its corrupt capitalist soul) and so, after an initial great triumph in the far North, had pushed his troops too far south, taking horrendous losses in the process. For a time it seemed like the only person who got what he wanted was Stalin, who, fearing Titoism on Mao’s part, and a possible Chinese connection to the Americans, was not unhappy when the Chinese decided to fight the Americans. But even he, so cold-blooded and calculating, miscalculated several times. He originally thought that the Americans would not enter the war, and then they did. If he was not at first unhappy with the idea of them fighting the Chinese (with the Russians sitting on the sidelines), then the long-range consequence for the Soviets would prove complicated indeed. The Chinese would remain bitter about what he did

not

do for them in those vital early months, and those feelings of resentment contributed to the Sino-Soviet split a few years later. But perhaps even more important, the Chinese entrance into the war had a profound and long-lasting effect on how Americans looked on the issue of national security.

It gave the ultimate push forward to the vision embodied in NSC 68. It greatly increased the Pentagon’s influence and helped convert the country toward far more of a national security state than it had previously been, so increasing the forces driving that dynamic that in ten years Dwight Eisenhower, in his farewell speech as president, would warn of a “military-industrial complex.” It would help define the Communist world, in American eyes, for years—and quite incorrectly—as a monolith, and so diminish the political influence of men like George Kennan, who placed greater emphasis on nationalism and age-old historical imperatives. It would poison American politics, where the great fear would become—for domestic political reasons rather than for geopolitical ones—losing a country to the Communists. Because of that, American policy toward Asia became deeply flawed, and this would profoundly affect American policy toward a country barely on the American radar screen at the time, Vietnam.

Certainly Kim Il Sung miscalculated, not just that the Americans would not send their troops to defend South Korea but the myth of his own popularity and that of his revolution, convinced as he was that two hundred thousand Southern peasants would rise up as one when his troops moved south. He not only failed to make his country whole but encouraged the Americans to upgrade the importance of South Korea, not only defending it militarily but financing its growth in the postwar era into an infinitely more viable society than his North. Fifty years after the end of the war, there were still American troops garrisoned there, and the South had become something of an economic beacon to underdeveloped nations, its economy infinitely more vital than that of the Soviet Union itself in the late 1980s. Comparably the North remained a sad, grim backwater, as xenophobic as it was totalitarian and economically destitute.

FOR MANY AMERICANS,

except perhaps a high percentage of those who had actually fought there, Korea became something of a black hole in terms of history. In the year following the cease-fire, it became a war they wanted to know less rather than more about. In China the reverse was true. For the Chinese it was a proud and successful undertaking, a rich part of an old nation’s new history. To them it represented not just a victory, but more important, a kind of emancipation for the new China from the old China, which had so long been subjugated by powerful Western nations. The new China had barely been born, and yet it had stalemated not merely America, the most powerful nation in the world, the recent conquerors of both Japan and Germany, but the entire UN as well, or by their more ideological scorekeeping, all the imperialist

nations of the world and their lackeys and running dogs. In that sense it had been a victory of almost immeasurable proportions, and it had been, in their minds, theirs and theirs virtually alone. The Russians had committed some hardware, but had held back at the critical moment on manpower, men who had talked big and then had cheered from the sidelines. The North Koreans had been boastful, far too confident of their own abilities, and then had failed miserably at crucial moments, and it was the Chinese who had saved them. It was not out of character and hardly a surprise in the eyes of the Chinese that the North Koreans, in their historic accounts of the war, largely withheld credit from the Chinese. They were not, the feeling went, very good about being saved. If the Chinese at that moment had lacked the military hardware to chase the Americans off Taiwan, then they had instead used their abundant manpower, their ingenuity, and the courage of their ordinary soldiers to stalemate the Westerners on land. Afterward, the rest of the world had been forced to treat China as a rising world power.

More than that of anyone else it was Mao’s personal victory. He had pushed to go ahead when almost everyone else had wavered and had feared that their brand-new China, already financially and militarily exhausted by the sheer struggle of taking power after the civil war, might fail. Mao was the one who had seen the political benefits, both international and domestic, of making a stand in Korea. If the consequences had turned out to be far bloodier than he had imagined, if the Americans with their superior weaponry had eventually fought better than he had expected and inflicted greater damage on his armies, then he could accept that; he had a tolerance for gore as part of the price of revolution, and he headed a nation that might not be rich in material things, but was very rich in manpower, in the numbers of men it could sacrifice on the battlefield on its way to greatness. That was something he had always believed in when most of the others around him hesitated. It was not that he knew the demographics better than the others in the leadership group; it was that he was willing to make the calculations more cold-bloodedly than they did.

What had been at stake in the Korean War, and it was to hang over subsequent wars in Asia, was the ability to bear a cost in human life, the ability of an Asian nation to match the technological superiority of the West with the ability to pay the cost in manpower. During Korea and soon enough in Vietnam, American military commanders and theorists alike would talk about the fact that life in Asia was cheaper than it was in the West, and they would see their job as one in which they used vastly superior military technology to attain a more favorable battlefield balance, even as their Asian adversaries were determined to prove to them that in the end that was not doable, that there would always be a

price and it would always be too high for an American undertaking so distant, and so geopolitically peripheral.

Because the Chinese viewed Korea as a great success, Mao became more than ever the dominant figure in Chinese politics. He had shrewdly understood the domestic political benefits of having his country at war with the Americans. As he had predicted, the war had been a defining moment between the old China and the new one, and it had helped isolate those supporters of the old China—those Chinese who had been connected to Westerners—and turned them into enemies of the state. Many were destroyed—either murdered or ruined economically—in the purges that accompanied and then followed the war. From then on there was no alternative political force to check Mao; he had been the great, all-powerful Mao before the war began, and now, more than ever, his greatness was assured in the eyes of his peers on the Central Committee, who were no longer, of course, his peers. Before the war he had been the dominant figure of the Central Committee, a man without equals; afterward he was the equivalent of a new kind of Chinese leader, a people’s emperor. He stood alone. No one had more houses, more privileges, more young women thrown at him, eager to pay him homage, more people to taste his food lest he be poisoned at one of his different residences. No one could have been contradicted less frequently. The cult of personality, which he had once been so critical of, soon came to please him, and in China his cult matched that of Stalin.

There was in all this a scenario not just for political miscalculation but for something darker, for potential madness with so much power vested in one man, a man to whom so much damage had been done earlier in his life. That was always a critical element of what happened next: Mao as a young man, not unlike Stalin, had been hunted too long and too relentlessly, as it were, by so many enemies; the deepest, most unwavering kind of paranoia grew out of that past and was the most natural part of his emotional and political makeup. At the same time he had become the principal architect of an entirely new political economic-social system. He existed and operated in a nation without any personal limits on him and yet where everyone could be an enemy. Both his power and his paranoia were without limits. He who had been for so long the ultimate outsider now lived a life of imperial grandiosity. He no longer needed to listen to others; if the others differed from him on issues, it was because they did not hold China’s welfare as close to their hearts as he did, and were perhaps enemies of his and of China as well—the two he judged to be the same.

He was sure that he was right on all issues—his words as they escaped his mouth were worthy of being codified as laws. China, he had decided,

his

China, was ready to rush into modernity—the Great Leap Forward, it was called, and the burden of turning a poor agricultural society into a modern industrial state virtually overnight fell on the peasants. If he had once been uniquely sensitive to their needs, more tuned to them as a political force than anyone else in the leadership, he now seemed prepared to put the entire burden of modernization, brutal though it would be, on them for his larger purpose. His new China would, if need be, be built on their backs. It was their job to make his dreams, no matter how unlikely, come true. The Great Leap Forward was probably the first example of a turn toward madness: as it went on, the peasants suffered more and more, under growing pressure to produce more agriculturally than ever before, even as there were conflicting pressures for them to convert to a kind of primitive industrial base, as if there were to be a small foundry in every Chinese backyard. The Great Leap Forward was always more vision than reality. Figures on agricultural production were severely doctored to make the program look like a success. Almost everyone in the bureaucracy knew that it was largely a failure—the phrase that the distinguished Yale historian Jonathan Spence used was “catastrophic hardship”—but for a long time no one dared challenge Mao. The genuine independence of the rest of the Central Committee seemed in decline; the power and authority of Mao in a constant ascent. His will had become the national will; his truths were everyone’s truths. He was never wrong. If he said that night was day, then night had become day.

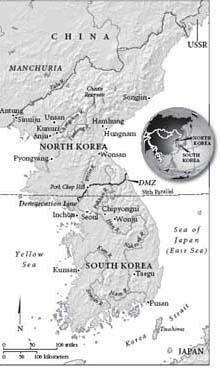

25. T

HE

K

OREAN

P

ENINSULA

A

FTER

T

HE

C

EASE-FIRE,

J

ULY

27, 1953

Because his hold over the government was so complete, because his need to dominate every decision was so total, he forced anyone who was a potential critic or dissenter, no matter how essentially loyal, into the most dangerous role. Those who challenged him were not merely wrong, they could become, if the issue were serious enough, enemies of the people. Those who thought they were his friends and peers and old colleagues were, it turned out, badly mistaken; they were his friends and allies only as long as they agreed with him on all issues all the time. No one suffered more than one of his oldest allies, Marshal Peng. He was a simple man who had always known his limits and thus his place, a true Communist, a man who always deferred to Mao on politics. But Peng was also a proud man, every bit as confident of his sense of the peasants’ welfare. Peng became a dissenter almost involuntarily—almost, it seemed, as if Mao wanted a break with him, wanted to turn on him and make him an enemy. By 1959, the early results of the Great Leap Forward were in and China was in the midst of a terrible famine. Yet ever higher agricultural yields were being reported. Almost every senior official understood this—that the chairman’s Great Leap was buttressed by lies and falsified statistics, but no one dared take him on.