The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (48 page)

Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

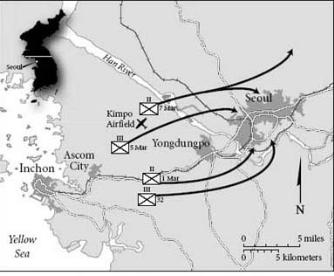

What made the tensions between the two men worse was Smith’s belief that the pressure was falsely driven, that it reflected not the need for a quicker battlefield victory as a means of cutting off the North Korean Army but instead a diversion, reflecting an obsession with public relations, the constant need from MacArthur’s headquarters for glory. Here the commands in Tokyo and Washington were badly split: Smith, Walker, and the Joint Chiefs, watching distantly from Washington, believed the wise course was to bypass Seoul itself, cut it off, and quickly move east to meet up with Walker’s forces, who were driving north. That, they hoped, would mean not just a major victory but the chance to bag much of the North Korean Army. To them MacArthur’s and Almond’s obsession with Seoul defeated the very purpose of the landing, because it might let much of the North Korean Army slip through. But they knew that MacArthur wanted the capture of Seoul on or before the very symbolic date of September 25, three months after the North Koreans had first crossed the thirty-eighth parallel. MacArthur had originally wanted September 20 as the date for Seoul’s liberation, but Almond had talked him out of that. To Smith, Almond was risking his Marines unnecessarily for a couple of extra lines in newspapers back home because that was what his commander wanted. He was not impressed. To him it was a gimmick, nothing more.

MEANWHILE, AT MACARTHUR’S

headquarters there was growing frustration with Johnnie Walker and the Eighth Army, which was having some early problems breaking out of its positions on the Naktong. Their frustrations were nothing compared to those felt by Walker. When Walker received his first briefing on Inchon on September 17, and he learned how lightly defended it had been, he became furious. “They expended more ammunition to kill a handful of green troops at Wolmi-do and Inchon than I’ve been given to defeat ninety percent of the North Korean Army,” Walker told a friend after the

briefing. He was aware that in a number of places his men were having trouble breaking out of their positions along the Naktong. The river, he believed, had served his troops as a great defensive barrier against the advancing North Koreans, but as it had protected his men from the In Min Gun, now it was slowing them down in their pursuit of the North Koreans. What angered him was the pressure on him from his superiors, and his lack of equipment, especially bridging equipment. First choice on all of it had gone to Tenth Corps, to help cross the Han River, where all the bridges had been blown. What enraged Walker was that these were essentially decisions made by the chief of staff’s office, that is, Almond’s headquarters, a reflection, he felt, that the dice were loaded against him.

MacArthur and his staff took none of this into account. At a staff meeting held aboard the

Mount McKinley

on September 19, with much of the senior Navy and Marine command present as well (“virtually a public meeting,” Clay Blair noted), MacArthur had spoken quite openly and in a very personal way about his frustrations with Walker, and about replacing him with someone more forceful. For Walker, it proved one insult too many. He called Doyle Hickey, the acting chief of staff, and tried to explain that there was a reason why his troops were moving slowly. “We have been bastard children lately,” he told Hickey “and as far as our engineering equipment is concerned, we are in pretty bad shape.” Then he added: “I don’t want you to think that I am dragging my heels, but I have a river across my whole front and the two bridges I have, don’t make much.”

Even as MacArthur was complaining about Walker, the Marines too were beginning to slow down as they faced far stronger resistance than Tokyo had expected. Almond wanted a de facto guarantee from Smith that the Marines would make the Seoul deadline. “I told [Almond] that I couldn’t guarantee anything. That was up to the enemy. We’d do the best we could and go as fast as we could,” Smith later said. It was not the answer Almond wanted. If Smith had been an Army officer, it is quite likely that he would have been relieved right then and there. Almond soon came up with his own battle plan designed to speed things up, but one that, in Smith’s view, would dangerously fragment the American forces into too many smaller units, rather than maximizing their superior firepower. One aspect of the Almond plan made Smith particularly nervous—in it there was a likelihood that American troops might hit a given part of the city from opposite directions and end up, in the chaos of battle, shooting at one another. He rejected Almond’s plan almost out of hand—the work, he believed, of an absolute amateur. It was a most serious dissent—a division commander rejecting a corps commander’s plan—and in the process he came perilously close to insubordination.

Some Marines did reach the outskirts of the capital on September 25, and so Almond was able to issue his communiqué saying the city had been taken. That seemed far from the truth to the men still fighting there. “If the city has been liberated,” an Associated Press reporter said the next day in his dispatch, “the remaining North Koreans did not know it.” Hard fighting in fact went on until September 28. The Americans won in the end because of their awesome firepower, but they had devastated the city in the process. Of the capture of Seoul, the British reporter Reginald Thompson wrote that it was “an appalling inferno of din and destruction with the tearing noise of dive bombers blasting right ahead, and the livid flashes of the tank guns, the harsh fierce crackle of blazing wooden buildings, telegraph and high tension poles collapsing in an utter chaos of wires…. Few people have suffered so terrible a liberation.”

The damage the harsh, unrelenting battle did to the relationship between Almond and the Marines would have serious consequences. Almond had delivered Seoul to MacArthur on time. He had shown, Clay Blair wrote, some of the same qualities he had displayed in World War II. He was “demanding, arrogant and impatient,” had a tendency to fragment his units, as well as to send units forward without sufficient reserves or very much concern about who, if anyone, was on their flanks. He was, Blair wrote later, “courageous to the point of recklessness, and expected everyone else to be. But this attitude was interpreted by many subordinate officers as a callous indifference to casualties and the welfare of his men.” He also “placed greater emphasis on the quick capture of real estate (Seoul) for psychological or publicity reasons than he did on the creation of a strong line (the anvil) to stop the leakage of the NKPA northward.” Of the varying criticisms made of him after the initial success at Inchon, that was the most serious one. Because of that, too many of the enemy managed to slip through what should have been a trap. “The public relations brigade,” Johnnie Walker privately called Tenth Corps in disgust. Yet if it was not the complete tactical success it might have been, Inchon remained in many ways a spectacular victory and a signature personal triumph for MacArthur, the high-water mark of his career. It broke the spirit of the North Korean military and opened all of South Korea to his forces.

Because Inchon was such a success, it changed the nature of MacArthur’s command. First of all there were some scores to settle. Those who had been for Inchon would be rewarded, and those who had questioned it now had to pay the price for their lack of faith. Just after Seoul was liberated, Walker’s pilot, Mike Lynch, watched in disbelief as MacArthur descended from his plane at the newly liberated Kimpo Airfield, walked right past Walton Walker, the three-star who had valiantly held his forces together in Pusan (“after some of the most vicious goddamn battles ever fought against all odds”), snubbing him completely, only to greet Almond warmly. “Ned, my boy,” he said. The snub was clear punishment for Walker’s having lined up too long with Joe Collins and the other Chiefs on Inchon, but there was worse to come, an act that had grave consequences for all United Nations forces. Walker had assumed that, after Inchon, Tenth Corps, out on loan, would be returned to him and folded back into the Eighth Army. Now he discovered that would not happen. Almond was going to keep his battlefield command of Tenth Corps as well as his chief of staff job. MacArthur was planning to split his command as they headed north.

10. T

HE

D

RIVE TO

S

EOUL,

S

EPTEMBER

16–28, 1950

While the original decision to give Tenth Corps to Almond had bothered a great many senior people both in Tokyo and Washington, it had been viewed at first as a temporary move, befitting the unusual circumstances of the moment. After all, Walker had been overwhelmed simply holding on at Pusan, and MacArthur’s headquarters was hardly rich in talent. But now Almond would remain permanently in charge of Tenth Corps, a separate unit that would not report to Walker at all. If anything, Walker would now have to compete with Almond’s force in the race north—and an additional amphibious landing was now being planned for Tenth Corps, this time at Wonsan, north of the thirty-eighth parallel on the east coast. In the great early flush of so significant a

victory, MacArthur was seizing even greater command control. At the same time, in a fateful way, things began to go wrong. Instead of supplies pouring into the newly captured Inchon for the moment of the kill, Inchon was being used to take men and supplies

out

. Instead of racing east from Seoul to create a giant pincers to trap the retreating North Koreans, MacArthur’s forces used this critical period to ready Tenth Corps ever so slowly and awkwardly for the next landing, this time embarking at Pusan and heading for Wonsan. There were the North Korean troops, trying to flee north pursued by Walker’s troops, and yet the Seventh Division, part of Tenth Corps, had road priority—as they headed south for Pusan and their next seaborne assault. So, on the narrow main supply route, any convoy moving north had to give way before the Seventh heading south, violating a basic Army canon: never lose contact with your enemy.

Wonsan was, in fact, a disaster in the making from the very start. The Navy was appalled by the idea. Admiral Turner Joy, who was in charge, wanted no part of it, fearing, rightly, that Wonsan harbor would be filled with mines. He tried to see MacArthur in Tokyo to protest, but was never allowed in. The amphibious assault on Wonsan was to prove in all ways a joke. It could have been accomplished far more quickly and easily if one of Walker’s Army units had simply driven north in conventional mode. Instead, everything went wrong. The planners were behind schedule, and delay followed delay. Friendly troops reached Wonsan by land first. Ignominiously enough, ROK troops from the Third and Capital Divisions got there on October 10, virtually unopposed. The next day, Walker flew into the port city along with Major General Earl Partridge, the theater Air Force commander. Finding the airport open, Partridge started using cargo craft to ferry supplies in for the South Koreans. Finally, on

October 19,

the troopships carrying the Marines arrived off Wonsan harbor. But Admiral Joy had been right, this time the Communists had deposited some two hundred mines in the harbor, and the Navy had only twelve minesweepers on hand. So the Marines had to stay in their ships while the minesweepers slowly cleared the harbor. Soon, in that prolonged wait, many of the Marines got seasick. Then a wave of dysentery hit. On one giant transport ship, 750 Marines were laid low with it. The Marines, aware that South Korean troops had already taken the town, called their landing “Operation Yo-Yo.” The final insult for such proud troops came when Bob Hope, the famed comedian who often entertained soldiers in combat areas, arrived in Wonsan and gave a USO show intended for the Marines, who were still waiting in the harbor in their ships. There on an improvised stage at the Wonsan hangar, he joked that this was the first time he had beaten the Marines ashore. “It’s wonderful seeing you all,” he told the relatively small audience of maintenance crews, South Koreans,

and some brass from the armada. “We’ll invite you to all our landings.” Only on October

25,

two weeks after the arrival of the ROKs, did the Marines come ashore.

But the real danger—and almost everyone in Tokyo and Washington knew it—was not the landing at Wonsan but the splitting of the command. Of all the unspoken rules in the doctrine of the American Army, this was perhaps the most sacrosanct. It was something that you just did not do. When American military men thought of split commands, they thought immediately of the annihilation of George Armstrong Custer’s forces at the Little Big Horn. In the future, along with Custer, they would think of Douglas MacArthur and Ned Almond, and the eventual tragedy up along the Chongchon and Yalu rivers. For here was Douglas MacArthur sending his troops into dangerous, hostile, unspeakably difficult terrain (with the weather, as he had once noted, starting to turn against them), and he was, in effect, doubling the vulnerability of each part of his force. It reflected many of the lesser qualities of Douglas MacArthur, but more than anything else it reflected his disrespect for his next potential enemy, the Chinese. That enemy had already studied him carefully, but he had not deigned to return the favor, and the men under his command would suffer bitterly for his carelessness.