The Cockroaches of Stay More (36 page)

Read The Cockroaches of Stay More Online

Authors: Donald Harington

The cockroach, fat and stupid-looking, will somehow arouse a fleeting pity in Sharon, pity that she will not have felt if it will not have been for the pity she will have taken on Alfonse and Letitia, sparing them. This dead, impaled cockroach, over which she will step as she will have stepped over Alfonse the day before, will cause her to recite aloud some old snatch of an elegy she has read in school: “And now I live, and now my life is done.”

Sharon will not know why she will be saying that aloud, but, thinking of poetry, she will be not totally unprepared for what she will find inside the house, in Larry’s study, in his typewriter: a poem. She will have known, of course, that he sometimes attempted poetry when he wasn’t analyzing it, and she will assume, even before reading it, that this will be his own creation. His black

IBM

Selectric will still be running, still be on. She will reach down to feel how warm it will be, and in doing so she will cause to fly up an enormous cockroach. This will not be, cannot be, Alfonse, nor the one she liberated from the garbage bag, nor any other cockroach she will ever have seen; it will be too large, and although she will have discovered, just yesterday, that cockroaches

can

fly, this one will be flying all over the place, like a bird, like a bat, and she will be much more afraid of it than of any insect she has ever seen. But it will at length fly through the door and away, and she will never see it again.

She will have one more fright before she can read the poem. She will see a mouse. If it will have been a black mouse, or a gray mouse, it will have made her cry out and jump, but it will be a white mouse, and it will not be totally a stranger, because it will be the same mouse who led the horde of cockroaches in their directive arrow and message.

The white mouse will be on the floor near Larry’s desk, and it will be looking at her, twitching its whiskers and bobbing its nose. And then it too, like the oversize roach, will decamp.

Sharon will return her glance to the poem, and read its title and begin reading it.

We will see her standing there, at Larry’s desk, reading. It will be almost like a painting by Vermeer. The lovely lady, the wonderful morning sunlight which seems to caress her face and her hands and the white, white sheet. She will read. She will smile.

And when the reading will be done, she will raise her eyes from the poem in the typewriter, and she will address the house: “Larry?”

IMAGO:

The Mockroach’s Song

If roach were man and man were roach,

the subjects both would brood and broach

are love, dependency, survival.

We trust you in your rearrival

to read this fable in reverse

and keep the world from getting worse.

We are the scurry of your ugly

despisèd motives—humble, bugly,

but not so bad we should be

kaput

.

You shot yourself in your own foot,

went nearly west. We kept you easter.

Before you blast off your own keister,

wise up, stay more, re-ken your kin.

We know you out, we know you in.

We drink your nectar, eat your shit.

We haven’t had enough of it.

You think you pine with love and grief?

Yet think how pitiful and brief

we are, your small, unloved familiars:

our hearts will bridge the Void. Will yours?

Some say your world will end in fire

and ours survive. Not so. No choir

can hymn or hum inhumanly.

Thou needest us. We needest Thee.

Grow up, earn Love, like us conceive

a God to pray to and believe.

Ring out bomb-doom and ring us true.

You live, we are, you die, we do.

Ding-dong the dang dumb don’ts to soundless hell.

In purple sympathy we twain shall dwell.

About the Author

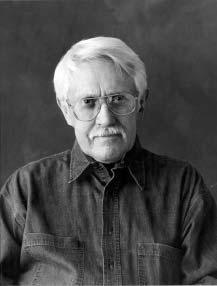

Donald Harington

A

lthough he was born and raised in Little Rock, Donald Harington spent nearly all of his early summers in the Ozark mountain hamlet of Drakes Creek, his mother’s hometown, where his grandparents operated the general store and post office. There, before he lost his hearing to meningitis at the age of twelve, he listened carefully to the vanishing Ozark folk language and the old tales told by storytellers.

His academic career is in art and art history and he has taught art history at a variety of colleges, including his alma mater, the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, where he has been lecturing for fifteen years. He lives in Fayetteville with his wife Kim.

His first novel,

The Cherry Pit

, was published by Random House in 1965, and since then he has published eleven other novels, most of them set in the Ozark hamlet of his own creation, Stay More, based loosely upon Drakes Creek. He has also published several non-fiction works on artists.

He won the Robert Penn Warren Award in 2003, the Porter Prize in 1987, the Heasley Prize at Lyon College in 1998, was inducted into the Arkansas Writers’ Hall of Fame in 1999 and that same year won the Arkansas Fiction Award of the Arkansas Library Association. He has been called “an undiscovered continent” (Fred Chappell) and “America’s Greatest Unknown Novelist” (Entertainment Weekly).

Table of Contents

INSTAR THE SECOND: Maiden No More,

INSTAR THE FOURTH: The Consequence,

INSTAR THE FIFTH: The Woman Pays,