The Classical World (87 page)

Read The Classical World Online

Authors: Robin Lane Fox

‘Luxury’ had always promoted a gap between practice and public profession. ByHadrian’s reign, it connected with changes in the scope of ‘justice’ and ‘freedom’. In our collection of Roman legal opinions, Hadrian’s own rulings survive identifiably; so does a collection, probably authentic, of the ‘opinions’ which he gave in answer to requests. In the history of Roman law, it is Hadrian who patronized a codification of the long-running edict of the annual praetors and saw that it was published in an agreed form.

9

Much of our inscribed record of his reign around the Empire is the record of his judging and deciding petitions and local disputes. In Italy, he even appointed four ex-consuls to judge cases submitted to them. When hearing cases himself, Hadrian was particularly remembered for including specialized experts in law as his advisers.

This body of advice, writings and tribunals may seem very far

removed from the giving of justice in the distant world of Homer and Hesiod. In the Roman Empire, judges were literate; textbooks and copies of previous rulings existed; complex distinctions of procedure and civil law under lay what Hadrian decided. Yet in another waythe distance travelled was no longer so very large. As in the Homeric world, justice was being rendered byan individual’s inquisition, which was not subject to the decisions of a jury. This change in the structure of jurisdiction had re-entered the classical world with the rise of King Philip and the age of monarchy. The randomly selected juries of classical democratic Athens were no longer the main type of public adjudication. There was also another telling change. In Hadrian’s reign a frank distinction between the ‘more respectable’ and the ‘more humble’ begins to be stated, for the first time in Roman legal texts.

10

The ‘more respectable’ included army-veterans, but also those with the rank (to be paid for) of city-councillor, let alone the Roman knights and senators. The ‘more humble’ extended down to propertyless vagrants and below. For the same crimes, these two social orders were now to be liable to different punishments: there was to be no flogging, no torture for respectable citizens, and no beheading, crucifixion or deportation, either. Previously, protection from these extreme penalties had been linked to possession of Roman citizenship and was founded on that cardinal principle of Roman liberty, the right to ‘call out’ or appeal. Now a ‘humble’ Roman citizen was liable to the most brutal penalties like any one else of low status, as if his citizenship carried no privilege. Respectable persons were protected because they were respectable, whether citizens or not.

Hadrian did not initiate this distinction, but in his reign there began to be explicitly ‘one penalty for the rich, one for the poor’. This development had older roots in Roman practice, and the punishment of lower-class citizens in Cicero’s Rome mayalso have been as savage as it now became. But the distinction was now in writing, and to many Romans (including Pliny) it was not even unjust. For ‘fair justice’, such people thought, was proportional, varying according to the class and worth of the recipient. Homer’s Odysseus, speaking moderately to his fellow nobles and thumping the lower classes with his sceptre, is no longer very far away.

This frank calibration of justice by social status devalued Roman

citizenship and went with a change in the scope of freedom. In Homer’s poems, ‘freedom’ had been freedom from enslavement or conquest, individual or collective. In classical Athens, it became the freedom of democracy, the freedom of the male citizens ‘to do whatever they decide’, with accompanying notions of their personal ‘freedom from’ undue influence. In the Roman Republic, founded by ending a monarchy, ‘freedom from’ one-man rule was historically a very strong value, together with the popular notion of a freedom which was ‘freedom from’ harassment by social superiors and the senators’ notions of ‘freedom for’ their senatorial order to say or do what it wanted. Under the emperors’ rule, freedom, as the opposite to slavery, was still prized in Rome’s slave-society, as it had been prized everywhere else in the classical world. But from the years of Augustus’ dominance onwards, only ‘traces’ (as Tacitus stressed) remained of the senators’ particular ‘freedom’, and throughout the Empire, the ‘freedom’ of cities and popular assemblies had become a matter only of degree. Under Hadrian, his beloved Athens was still called a ‘free city’, but it honoured him, the emperor, as an Olympian god. On the Greek island of Lesbos, inscriptions honoured Hadrian as a ‘liberator’ while also paying him divine honours.

11

The former ‘freedom’ of Athens and Sparta, so Pliny observed, was now only a ‘shadow’: in general, Roman rule had curbed or abolished democracies and popular rule in the Greek subject-cities. At Rome, meanwhile, the ‘resolutions’ of the Senate had acquired the force of law, because they communicated the emperor’s own considered wish or even, in due course, the very words of his speech. In

AD

129 the consuls ‘brought forward a bill, based on a paper of Imperator Caesar Hadrian Augustus, son of Trajan Parthicus, grandson of the deified Nerva, greatest First Citizen, father of the state, on 3 March…’.

12

The result passed into our Roman law-books. The ‘First Citizen’, who initiated it, was himself now ‘released from the laws’, a status which was justified (for legal minds) by the law which had set out the Emperor Vespasian’s powers.

‘Liberty’ of speech and decision, as Cicero had known it, was now dead. While in Greece, in his mid-twenties, Hadrian had been one of the manyhearers of a noted teacher, Epictetus.

13

Epictetus was himself the ex-slave of a freedman in the emperor’s household: he discoursed

on freedom, justice and moderation to large audiences, people who were mostly drawn from the respectable young men of cities in the Greek-speaking world. Epictetus taught the doctrine of Stoic philosophers which had been formulated in the decade after Alexander and was known, too, to Cicero and his contemporaries. For Epictetus, ‘freedom’ was an individual’s reasoned control of his desires and passions. A rich man, torn by fears and wants, was therefore as much, even more, of a ‘slave’ as any slave in the real world. Epictetus’ surviving teachings never even mention his own experience of slavery in his youth. Rather, with first-hand illustrations, he spoke of the court-life around a Roman emperor as ‘futile’ slavery.

In the classical Greek world, the freedom which had belonged with the greatest cultural expression was the freedom of democratic citizens, the political freedom of a male majority which was limited only by decisions to which they themselves consented. In Hadrian’s world, freedom had become only a freedom from bad, cruel emperors or the unpolitical ‘freedom’ of an individual’s control over his desires. From an admired teacher, Epictetus, Hadrian had heard what Pericles or Alexander never heard from theirs, that a public career at the centre of power was a dangerous, disturbing vanityand that its public honours were futile.

As a many-sided man, Hadrian would not have forgotten this view of the world which he dominated. But it was onlyone view, in a mind which entertained so manyothers. At his huge villa at Tibur, Hadrian could walk through monuments named after great places in the classical Greek world: there was a Lyceum and an Academy, places where Socrates, Plato and Aristotle had taught, a Tempe where the Muses had once played, and a Prytaneum, where the free councillors of Greek democracies had typically dined and attended to public business. In the gardens of his villa, Hadrian even had a so-called ‘underworld’, a representation of Hades: it is probably still to be seen in some of the underground tunnels on the site. His own tastes in philosophywere for the Epicurean school, for whom the fear of death was an unwarranted ‘disturbance’ and the tales of an afterlife only fables for the superstitious masses.

From his provinces, Hadrian had already answered requests about the persecution of a most ‘wicked superstition’, the beliefs held by

members of the Christian churches. Hadrian’s answers continued to insist that trials must involve individual prosecutors, people who would bring formal charges in public against these Christians. Contrary to the wishes of some leading provincials, he thus insisted that the persecution of Christians must be a formal process, to be publicly pursued with rules. By his judgements, his letters and his edicts, it was Hadrian who now made the laws by which justice was done. As emperor, he was freed from the laws; as an educated man, he was personally free from fears of the underworld. Nonetheless, in a famous poem, he addressed consolatory words to his ‘little soul’, a future wanderer in a chillyand humourless afterlife. Long centuries of change in the scope of justice, freedom and luxury lay behind Hadrian’s outlook from his villa garden. But he had no idea that the Christians, whose harassment he regulated, would then overturn this world by antiquity’s greatest realignment of freedom and justice: the ‘under-world’ would no longer be a garden-designer’s fancy.

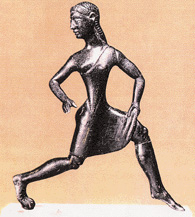

1. A pentathlete doing the long jump with hand-held weights. Amphora of the Tyrrhenian group,

c

. 540

BC

.

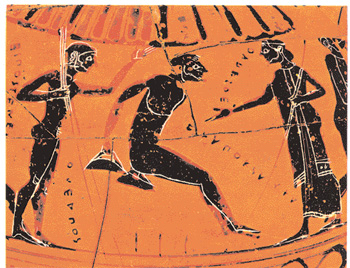

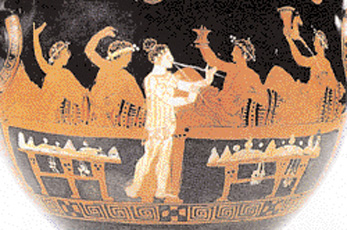

2. A slave-girl entertains male symposiasts with music: red-figure

krater

, or mixing-bowl, fourth century

BC

.

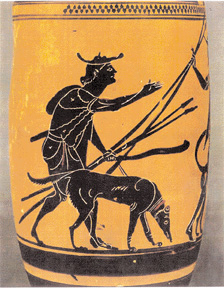

3. Hunter, wearing the typical

petasos

-hat, with his spears and hound,

c

. 510–500 bc, Edinburgh painter, Athens.

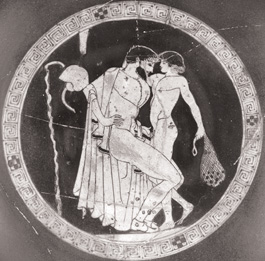

4. A sexually aroused older male fondles a young, probably prepubic, boy in a gym or wrestlingspace (

palaestra

). Brygos painter, Athens,

c

. 480

BC

.