The Chinese Maze Murders (9 page)

Read The Chinese Maze Murders Online

Authors: Robert van Gulik

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Mystery & Detective, #Police Procedural

“That flag,” Judge Dee answered, “I put up myself. It only means that I, the magistrate, have temporarily placed this district under martial law, as I am entitled to do in a state of emergency.”

The guildmasters smiled and bowed deeply.

“We perfectly understand Your Honour’s discretion!” the eldest said gravely.

Judge Dee did not comment further on this but broached quite a different subject. He requested the masters to send him that very afternoon three elderly men qualified and

willing to serve in the tribunal respectively as senior scribe, head of the archives, and warden of the jail; and a dozen dependable youngsters to serve as clerks. The judge further requested them to lend the tribunal two thousand silver pieces to pay for elementary repairs of the court hall and for the salaries of the personnel; this sum would be paid back as soon as the case against Chien Mow had been concluded and his property confiscated.

The guildmasters readily agreed.

Finally Judge Dee informed them that the next morning he would open the case against Chien Mow, and asked them to make this fact known throughout the district.

When the guildmasters had taken their leave the judge went back to his private office. There he found Headman Fang waiting for him together with a good-looking young man.

Both knelt before the judge. The young man knocked his head on the floor three times in succession.

“Your Honour,” Fang said, “allow me to present my son. He was kidnapped by Chien’s henchmen and compelled to work as a servant in his mansion.”

“He shall serve under you as a constable,” Judge Dee said. “Did you find your eldest daughter?”

“Alas,” Fang replied with a sigh, “my son has never seen her and the most diligent search did not produce any trace of her. I closely questioned the steward of Chien’s mansion. He remembers that at one time Chien Mow expressed the desire to acquire White Orchid for his harem but maintains that his master dropped the matter when I refused to sell my daughter. I do not know what to think.”

Judge Dee said pensively:

“It is your assumption that Chien Mow kidnapped her, and you may yet be proved right. It is not unusual for a man like Chien to keep a secret love nest outside his mansion.

On the other hand we must also reckon with the possibility that he had really nothing to do with her disappearance. I shall question Chien on this subject and institute a thorough investigation. Do not give up hope too soon!”

As the judge was speaking, Ma Joong and Chiao Tai came in.

They reported that Corporal Ling had executed his orders to the letter. Ten soldiers were stationed at each of the four city gates and a dozen of Chien’s men were locked in each gate tower. The number of prisoners had been increased by five ex-soldiers who had deserted to escape punishment for real crimes. Corporal Ling had demoted to water carriers the loafers who had been guarding the gates before.

Ma Joong added that Ling had all the qualities of a good military man; he had deserted because of a quarrel with a dishonest captain and was overjoyed at being once more in the regular army.

Judge Dee nodded and said:

“I shall propose that Ling is made a sergeant. For the time being we shall leave the forty men stationed at the gates. If their morale remains good I propose to quarter them all together in Chien’s mansion. In course of time I shall designate that as garrison headquarters. You, Chiao Tai, will remain commanding officer of those forty men and the twenty we trained here in the tribunal, till the soldiers I shall send for have arrived.”

Having thus spoken the judge dismissed his lieutenants. He took up his brush and drafted an urgent letter to the far-away prefect describing the events of the past two days. The judge added a list of the men he wanted re-enlisted and a proposal that Corporal Ling be promoted to sergeant. Finally he requested that one hundred soldiers be send to Lan-fang as permanent garrison.

As he was sealing this letter the headman came in. He reported that a Mrs. Yoo had come to see the judge. She was waiting at the gate of the tribunal.

Judge Dee looked pleased.

“Bring her in!” he ordered.

As the headman was showing the lady into Judge Dee’s office he gave her an appraising look. She was about thirty years old and still a remarkably beautiful woman. She was not made up and very simply dressed.

Kneeling before the desk she said timidly:

“Mrs. Yoo

nee

Mei respectfully greets Your Honour.”

“We are not in the tribunal, Madam,” Judge Dee said kindly, “so there is no need for formality. Please rise and be seated!”

Mrs. Yoo rose slowly and sat down on one of the footstools in front of the desk. She hesitated to speak.

“I have always,” Judge Dee said, “greatly admired your late husband Governor Yoo. I consider him as one of the greatest statesmen of our age.”

Mrs. Yoo bowed. She said in a low voice:

“He was a great and a good man, Your Honour. I would not have dared to intrude upon Your Honour’s valuable time were it not that it is my duty to execute my late husband’s instructions.”

Judge Dee leaned forward.

“Pray proceed, Madam!” he said intently.

Mrs. Yoo put her hand in her sleeve and took out an oblong package. She rose and placed it on the desk.

“On his deathbed,” she began, “the Governor handed me this scroll picture which he had painted himself. He said that this was the inheritance he bequeathed to me and my son. The rest was to go to my stepson Yoo Kee.

“Upon that the Governor started coughing and Yoo Kee left the room to order a new bowl with medicine. As soon

as he had gone the Governor suddenly said to me: ‘Should you ever be in difficulties you will take this picture to the tribunal and show it to the magistrate. If he does not understand its meaning you will show it to his successor, until in due time a wise judge shall uncover its secret.’ Then Yoo Kee came in. The Governor looked at the three of us. He laid his emaciated hand on the head of my small son, smiled and passed away without saying another word.”

Mrs. Yoo broke down sobbing.

Judge Dee waited until she was calmer. Then he said:

“Every detail of that last day is important, Madam. Tell me what happened thereafter.”

“My stepson Yoo Kee,” Mrs. Yoo continued, “took the picture from my hands saying that he would keep it for me. He was not unkind then. It was only after the funeral that he changed. He told me harshly to leave the house immediately with my son. He accused me of having deceived his father and forbade me and my son ever to set a foot in his house again. Then he threw this scroll picture on the table and said with a sneer that I was welcome to my inheritance.”

Judge Dee stroked his beard.

“Since the Governor was a man of great wisdom, Madam, there must be some deep meaning in this picture. I shall study it carefully. It is my duty to warn you, however, that I keep an open mind as to the portent of its secret message. It may either be in your favour or prove that you have been guilty of the crime of adultery. In either case I shall take appropriate steps and justice shall take its course. I leave it to you, Madam, to decide whether you will want me to keep this scroll or whether you prefer to take it back with you and withdraw your claim.”

Mrs. Yoo rose. She said with quiet dignity:

“I beg Your Honour to keep this scroll for study. I pray

to Merciful Heaven that it will grant you to solve its riddle.”

Then she bowed deeply and took her leave.

Sergeant Hoong and Tao Gan had been waiting outside in the corridor. Now they came in and greeted the judge. Tao Gan was carrying an armful of document rolls.

The sergeant reported that they had inventoried Chien Mow’s property. They had found several hundred gold bars and a large amount of silver. This money they had locked in the strongroom together with a number of utensils of solid gold. The women and the house servants had been confined to the third courtyard. Six constables of the tribunal and ten soldiers had been quartered in the second courtyard under supervision of Chiao Tai, to guard the mansion.

Tao Gan placed with a contented smile his load of documents on the desk. He said:

“These, Your Honour, are the inventories we made, and all the deeds and accounts that we found in Chien Mow’s strongroom.”

Judge Dee leaned back in his chair and looked at the pile with undisguised distaste.

“The disentangling of Chien Mow’s affairs,” he said, “will be a long and tedious task. I shall entrust this work to you, Sergeant, and Tao Gan. I don’t expect that this material will contain anything more important than evidence of unlawful appropriation of land and houses and petty extortion. The guildmasters have promised to send me this afternoon suitable persons to take up the duties of the clerical personnel, including a head of our archives. They should be useful in working out these problems.”

“They are waiting in the main courtyard, Your Honour,” Sergeant Hoong remarked.

“Well,” the judge said, “you and Tao Gan will instruct them in their duties. Tonight the head of the archives will assist you in sorting out these documents. I leave it to you to draft for me an extensive report with suggestions as to how Chien Mow’s affairs should be dealt with. You will keep apart, however, any document that has a bearing on the murder of my late colleague, Magistrate Pan.

“I myself wish to concentrate on this problem here.”

As he spoke the judge took up the package that Mrs. Yoo had left with him. He unwrapped it and unrolled the scroll picture on his desk.

Sergeant Hoong and Tao Gan stepped forward and together with the judge they looked intently at the picture.

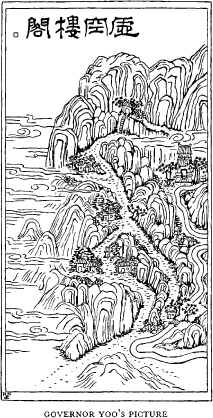

It was a medium-sized picture painted on silk, representing an imaginary mountain landscape done in full colours. White clouds drifted amoung the cliffs. Here and there houses appeared amidst clusters of trees, and on the right a mountain river flowed down. There was not a single human figure.

On top of the picture the Governor had written the title in archaic characters. It read:

BOWERS OF EMPTY ILLUSION

The Governor had not signed this inscription, there was only an impression of his seal in vermilion.

The picture was mounted on all four sides with borders of heavy brocade. Below there had been added a wooden roller and on top a thin stave with a suspension loop. This is the usual mounting of scroll pictures meant to be hung on the wall.

Sergeant Hoong pensively pulled his beard.

“The title would seem to suggest,” he remarked, “that this picture represents some Taoist paradise or an abode of immortals.”

Judge Dee nodded.

“This picture,” he said, “requires careful study. Hang

it on the wall opposite my desk so that I can look at it whenever I like!”

When Tao Gan had suspended the picture on the wall between the door and the window, the judge rose and walked over to the main courtyard.

He saw that the prospective members of his clerical staff were decent looking men. The judge addressed them briefly, and concluded:

“My two lieutenants will now instruct you. Listen carefully, for tomorrow you will have to start your duties when I hold the morning session of this tribunal.”

Seventh Chapter

THREE ROGUISH MONKS RECEIVE THEIR JUST PUNISHMENT; A CANDIDATE OF LITERATURE REPORTS A CRUEL MURDER

T

HE

next morning, before the break of dawn, the citizens of Lan-fang began trooping to the tribunal. When the hour of the morning session approached a dense crowd filled the street in front of the main gate.

The large bronze gong was sounded three times. The constables threw the double gate open and the crowd poured inside and into the court hall. Soon there was not a single standing place left.

The constables ranged themselves in two rows to right and left in front of the dais.

Then the screen at the back was pulled aside. Judge Dee ascended the dais clad in full ceremonial dress. As he seated himself behind the bench his four lieutenants took up their position by his side. The senior scribe and his assistants stood next to the bench, now covered with a new cloth of scarlet silk.

A deep silence reigned as the judge took up his vermilion brush and filled out a slip for the warden of the jail.

Headman Fang took it respectfully with two hands and left the court hall with two constables.

They came back with the elder of Chien’s two counsellors. He knelt in front of the dais.

Judge Dee ordered:

“State your name and profession!”

“This insignificant person,” the man spoke humbly, “is

called Liu Wan-fang. Until ten years ago I was the house steward of Chien Mow’s late father. After the latter’s death Chien kept me as his adviser. I assure Your Honour that I have always on every possible occasion urged Chien to mend his ways!”

The judge observed with a cold smile:

“I can say only that your attempts had a remarkably small result! The tribunal is collecting and sifting the evidence of your master’s crimes; doubtless this material will prove your complicity in many of Chien’s misdeeds. However, at present I am not concerned with the minor crimes you and your master committed. For the present I wish to confine myself to the major issues. Speak up, what murders did Chien Mow commit?”