The Child Thief (8 page)

Authors: Brom

Wolf

T

he child thief sat on a bench near the playground. Buildings loomed over him on all five sides of the large courtyard. As morning pushed into noon, the beehive of apartments began to wake up. He scanned the balconies, alert for any sign of wayward youth, but mostly found himself confronted with the same tired, hungover faces of the adults. They congregated in small clusters, lounging listlessly about the balconies, often with their apartment doors propped open and stereos blasting out into the courtyard. There was laughter here and there, but for the most part it sounded mean. Many of the people just stared blankly, their eyes glazed over, reminding Peter of the dead in the Mist.

A gleeful squeal caught Peter’s ear, followed by a burst of spirited laughter that drew him like candy.

A few younger kids had braved the drizzle to slip down the slide and climb the monkey bars. They formed teams and began an energetic game of tag.

The child thief watched them, smiling. Here, among so much drudgery—oblivious to the profane graffiti marring every available surface—these children could find joy.

They can always find joy

, he thought,

because they still have their magic

.

Peter found himself wanting nothing more than to run and play with them, the same deep desire he had when he first came across children all those long years ago. Only things hadn’t gone so well then. His smile faded.

No, that had been a day of hard lessons

.

HE WAS SIX

years old by then, slipping silently through the woods in his raccoon pelt. It flapped out behind him like a cape, the long striped tail bouncing in rhythm with his stride. He wore the head pulled over his face, like a hood, and his gold-flecked eyes peered out from the raccoon mask, scanning the woods, searching for game. It was spring, so he wore only a loincloth and rawhide boots beneath his coon skin. He carried a spear in each hand and a flint knife tucked into his belt. His body was painted with berry juice and mud to disguise his scent. Goll had taught him that, as well as the importance of always carrying two spears: a light one for game and a stouter one for protection against the larger beasts in the forest.

Peter placed a handful of walnuts in the center of a clearing, then ducked beneath a tall cluster of bushes. When he spied two brown squirrels in a nearby tree, he cupped his hands and mimicked a turkey foraging. Goll had taught him this trick too, that it was better to mimic an animal other than the one you were hunting, because rarely could you fool an animal with its own call, and nothing brought game quicker than the sound of other animals feeding.

Sure enough, both squirrels scurried his way. Peter slowly set the larger spear down and hoisted the light spear to his shoulder. The squirrels saw the nuts, saw each other, and raced for the prize.

Peter stood and threw. The spear hit its mark, leaving one squirrel behind as the other raced away, chattering angrily at Peter.

Peter whooped and leaped up.

No spider soup for me

, he thought.

Tonight I get squirrel stew

.

A wolf trotted into the clearing and stood between Peter and his prize. The wolf had only one ear.

Peter froze.

The beast locked its dark eyes on Peter. Its lips peeled back as though it were actually grinning.

Peter snatched up his heavy spear and thrust it out before him. “No,” Peter said. “Not this time.”

A low growl rumbled from the wolf’s throat.

Peter held his ground. The wolf had plagued him relentlessly over the last several months. Every time Peter made a kill, the wolf showed up and stole his meal. Peter was tired of spider soup. Today he would keep his prize.

The wolf’s eyes laughed at Peter, taunting the boy, daring him, as though it would like nothing better than to tear his throat open.

Peter swallowed loudly, his mouth suddenly dry. Goll had told him there was only one way to master the wolf: to attack it head-on. “Wolf is hunter,” he’d said. “When you hunt wolf, wolf get mixed up. No know what to do. Then you beat wolf. You will see. Show fear,” Goll had laughed. “Then wolf will eat you. A-yuk.”

Now

, Peter told himself.

Rush in. Stab it through the heart

.

The wolf lowered its head and began to slowly circle the boy. Peter knew what the wolf was up to, they’d played out this dance many times. The wolf was trying to cut off his retreat, trying to get between him and the nearest tree. Peter knew if he took his eyes off the wolf, even for a second, it would attack.

The wolf let loose a loud snarl.

Peter glanced toward the tree.

The wolf charged.

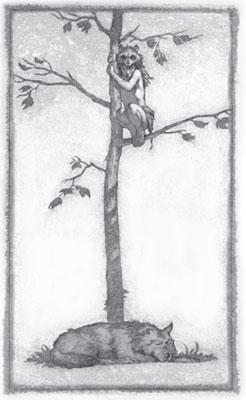

Peter yelped, dropped his spear, and ran. Fortunately, even at six, Peter was as fleet and agile as a squirrel. He dashed across the clearing and leaped for the tree, catching a low branch, then swung up. There came a loud clack of teeth and a sharp tug that almost pulled him from the branch. Peter scampered up a few more limbs before daring a glance below.

There, looking up at him, was the wolf, the raccoon tail dangling from its jaws.

The wolf circled the tree a few times, then trotted over to the dead squirrel.

Peter watched from his small, uncomfortable perch as the wolf devoured

his

dinner.

When the wolf was finished, it curled up beneath the tree and went to sleep.

As the long day slowly passed, Peter did his best to keep his legs from falling asleep and himself from falling out of the tree. By dusk, his whole body was numb and he had resigned himself to a miserable night.

“Well, look there,” called a gritty voice. “A Peterbird.”

Both Peter and the wolf looked up. Goll appeared above them on a short ledge.

Goll glanced at the wolf, what was left of the squirrel, then back up at Peter. He grinned. “You feed old one-ear again? A-yuk.”

Peter’s face colored and he looked away.

Goll laughed.

Goll leaped down from the stones and strolled through the underbrush toward the clearing. The wolf, knowing the routine, simply gave Goll a disdainful look and loped off.

Peter dropped from the tree, retrieved his spears, and slunk over to Goll.

Goll held up a large rabbit. “Goll will eat good tonight.” He nudged the remains of the squirrel with his toe. “Look like Peter get spider soup again. A-yuk.”

Peter’s shoulders slumped. “Ah, Goll. C’mon.”

“You want to eat good. You must hunt good.”

Peter kicked at the scraps of squirrel fur and followed Goll glumly back to the cave.

PETER DIPPED HIS

spoon into the bowlful of dark, soupy muck. He raised it to eye level and looked from the clot of soggy spider legs over to the half-eaten rabbit in Goll’s hand. The aroma of the roasted meat filled the entire cave. Goll licked the grease off his fingers, smacking loudly as he grumbled contentedly.

“Please?” Peter asked.

Goll shook his head.

“Just a few bites?”

“You know rule. You eat what you kill. You want rabbit, you kill own rabbit. A-yuk.”

“How am I supposed to do that with that stupid wolf following me?”

“You need kill wolf.”

Peter was quiet for a long time. “Goll, will you kill the wolf? Please?”

Goll shook his head. “Not hunting me.”

Peter let out a sigh and sat his bowl down. He stood up, walked to the cave entrance, and looked out into the night. He could see the stars twinkling through the spring leaves. He thought of his mother; sometimes he could close his eyes and actually smell her hair. He wondered what they were eating back in the great house, wondered why they’d left him for the beasts. He slapped one of the boots hanging across the entranceway, watched it swing, and wondered what the child had been like who had worn it, if that child had been left in the woods by its family.

“Goll?”

“A-yuk.”

“Whose shoes are these?”

“Little boys. Little girls.”

“Why do you have their shoes?”

“Must take them off before you can eat them.”

“Eat them?” Then he understood. “The

children?

”

“A-yuk.”

“You

eat

children?”

“Only when I can catch them.”

Peter stared silently at the shoes. “I don’t think I would like to eat children.”

“You would like. Very tender. Very juicy. Much better than spider soup.”

“Where do children come from?”

“From village.”

“Where’s the village?”

“

NO!

No speak of village. You never go near village. Men are there. Men very bad.

Very

dangerous.”

“More dangerous than the wolf?”

“Yes. Very more dangerous.”

Peter tapped the shoe again. It would be nice to have another kid around. “Goll, if you catch another one, can I keep it? We could build a cage for it. Okay?”

Goll cocked his head at Peter. “Peter, you very strange. You stay away from village.”

Peter came and sat back down next to the fire.

He looked at the hind leg of the rabbit in Goll’s bowl, then up at Goll, and smacked his lips.

“No begging. Hate begging.”

Peter stuck out his lower lip.

Goll rolled his eyes and frowned. “Here,” he grunted. “Take it.” Goll slid the bowl over to Peter, watched the boy devour the rabbit leg. After a bit, a smile pricked at the corners of the moss-man’s mouth. He shook his head, then crawled beneath his furs and went to sleep.

Peter finished the rabbit, lay back, enjoying the warmth of the meat in his belly. His eyes grew heavy.

Sure would be nice to have another kid to play with

, he thought.

I could teach it to hunt and

—Another thought came to Peter.

Why, together we could kill that mean old wolf

. Peter found he was now wide awake.

I bet I could catch one. Why, I know I could

.

PETER WATCHED THE

men through a knot of berry bushes. He’d set off before daybreak in search of the village, venturing far south of Goll’s hill, farther than he had ever dared before, and had come across a road, and not long thereafter heard horses. He’d trailed them most of the morning and they now stood drinking at a stream. Four men stretched their legs beside the horses, stout figures with thick braided mustaches and full growths of beard, brass rings in their ears, wearing leather breeches and woolspun tunics. Three of them had great long swords strapped to broad, bronze-studded belts. The fourth man wore hides and carried a double-bladed ax. After living with Goll so long, he thought these men to be fearsome and giant. Peter understood why Goll was so afraid of them.

There was also a wide-faced, solid woman with flaxen hair that ran down her chest in thick braids. She wore a long dress and, atop her broad hips, a wide belt adorned with swirling brass hoops. But it was the children that captivated Peter. He pushed the hood of his raccoon pelt back to get a better look. There were three of them: two boys about his age and a girl who looked a couple years younger. The boys wore only britches and sandals, the girl a bright red dress. Peter watched mesmerized as they chased each other round and round, leaping over logs and skipping through the stream.

One boy would tag the other and the chase would start anew. The little girl chased both of them, shouting for them to let her play until they finally got after her, their faces twisted up and their hands clutching the air like claws. The girl went screaming to her mother, leaving the two boys falling over themselves with laughter. Peter caught himself laughing along with them, and had to cover his mouth. It looked like fun.

They could play that game at Goll’s hill

, Peter thought, and now, more than ever, he wanted to catch one.

He eyed the men, wondering how to grab a child with them so near, decided he needed to be closer, and slipped up from tree to tree.

One of the boys came bounding into the woods, sprang over a bush, ducked around the tree, and came face to face with Peter. Both boys were so surprised that neither knew what to do.

The boy cocked his head to the side and gave Peter a queer look. “Are you a wood elf?”

“No. I’m a Peter.”

“Well then I’m

a

Edwin. Want to play?”

Oh, yes indeed

, Peter thought, nodded, and gave the boy a broad grin. He started to grab the boy when the girl rounded the tree. She saw Peter’s raccoon cape, the red and purple body paint, let out an ear-piercing shriek, and took off.

“Edwin,” bellowed one of the men. “Come back here.”

Peter heard heavy boots tromping his way and ducked back into the woods.

The man came around the tree and glared at the boy. “I told you to stay close.” The man scanned the trees. “There are wild things in these hills. Nasty boogies that live in holes. They steal little boys like you. And do you know what they do with them?”

The boy shook his head.

“They make stew out of their livers and shoes out of their hides. Now come along. We’ve much ground to cover by dark.”

PETER ARRIVED AT

the village well after dark. His feet and legs ached, his stomach growled. But he ignored his body’s grumblings, there was only one thing on his mind—the

boy

.

He waited in the trees until the men finished putting away the beasts, until there was no one moving in the night but him. There were a dozen roundhouses similar to the one he’d been born in, plus a sprawling stable. These were built around a large square. Pigs grunted, and chickens clucked in a pen somewhere.

Peter slipped silently in among the structures, feeling exposed out among the buildings, sure he was being watched, that the huge, brutish men were waiting for him around every corner. He pulled out his flint knife and ducked from shadow to shadow, sniffing, alert to the slightest sound. He wrinkled his nose; the village stank of beasts, sour sweat, and human waste. Peter wondered why anyone would want to live here instead of in the woods.