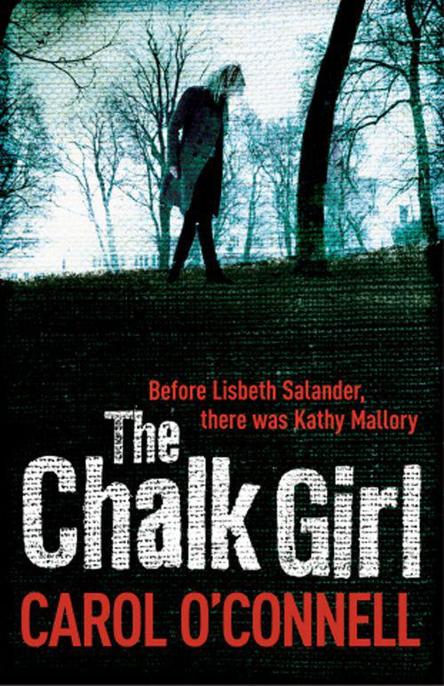

The Chalk Girl

The little girl appeared in Central Park: red-haired, blue-eyed, smiling, perfect – except for the blood on her shoulder. It fell from the sky, she said, while she was looking for her uncle, who turned into a tree.

Poor child

, people thought. And then they found the body in the tree.

For NYPD detective Kathy Mallory, there is something about the girl that she understands. Mallory is damaged, they say, but she can tell a kindred spirit. And this one will lead her to a story of extraordinary crimes; murders stretching back fifteen years, blackmail and complicity and a particular cruelty that only someone with Mallory’s history could fully recognise. In the next few weeks, Kathy Mallory will deal with them all . . . in her own way.

Carol O’Connell is one of the finest writers of contemporary thrillers, with her intoxicating mix of rich prose, resonant characters and knife-edge suspense. She lives in New York.

CAROL O’CONNELL

Copyright © 2012 Carol O’Connell

The right of Carol O’Connell to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2012

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

eISBN : 9780755385409

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

This book is dedicated to my cousin John, a vet from the Vietnam era, a laid-back soul with scuffed boots, a ’63 Chevy and a dry sense of humor. He liked ballgames and cigarettes. A working man who rolled his own, he claimed no ambitions beyond the next Saturday night.

And he was a man of mystery.

My best memory of him is a warm summer day, sailing down the coast of Massachusetts in an old wooden boat full of cousins and cold beer. We dropped anchor in a harbor, where we were surrounded by boats a bit larger, but then a luxury craft pulled up alongside. It was

huge

. A crowd of well-dressed, smiling people – so many teeth and so white – leaned over the rail to wave at us, and that was confusing. We do not come down from yachting people, and we didn’t know any of

them

. So . . . what the—

Then John, the most lax dresser among us, stood up in torn jeans and a not-quite-white tee. Cheers went up; they were waving at

him

. He crushed his beer can in one hand, waved back and then waved them the hell away. Apparently, John

knew

yachting people; he just didn’t have much use for them. And the rest of us never got the backstory on that day. That was John Herland, man of mystery, and when he died, I’m sure he was missed by yachtsmen everywhere, but deeply missed by me.

On the day I was born, I ran screaming from the womb. That’s what my father tells me when I bring home a story about the Driscol School.

—Ernest Nadler

The first outcry of the morning was lost in a Manhattan mix of distant sirens, barking dogs and loud music from a car rolling by outside the park. The midsummer sky was the deep blue of tourist postcards.

No clouds. No portents of fear.

A parade of small children entered the meadow. They were led by a white-haired woman with a floppy straw hat and a purple dress that revealed blue-veined calves as she crossed the grass, moving slowly with the aid of a cane. Her entourage of small day campers showed great restraint in keeping pace with her. They wanted to run wild, hollering and cartwheeling through Central Park, all but the one who waddled with an awkward gait of legs pressed close together – the early warning sign of a bladder about to explode.

Mrs Lanyard read aloud from a guidebook. ‘The flock of grazing sheep was removed from Sheep Meadow in 1934.’ This was followed

by a children’s chorus of disappointed groans and one shy lament, ‘I have to pee.’

‘Of course you do.’ There was always one. It never failed. The sardonic Mrs Lanyard raised one hand to shade her eyes as she gazed across the open expanse of fifteen acres spotted with people, their bikes and beach towels, baby strollers and flying Frisbees. She was looking for her assistant, who had gone off to scout the territory ahead for a public toilet. ‘Soon,’ she said to the child in distress, knowing all the while that a toilet would not be found in time. No field trip was complete without the stench of urine on the bus ride home.

After corralling her young charges into a tight cluster, she counted noses for the third time that morning. No children had been lost – but there was one too many. She spied an unfamiliar mop of curly red hair at the back of the ranks. That little girl was definitely not enrolled in the Lanyard Day Camp for Gifted Children – not that Mrs Lanyard regarded any of these brats as anything but ordinary. However, their parents had paid a goodly sum for a prestigious line on a six-year-old’s résumé, and the extra child was poaching.

What an odd little face – both beautiful and comical, skin white as cream for the most part and otherwise dirty. The little girl’s grin was uncommonly wide, and there was an exaggerated expanse between the upturned nose and full lips. Her chin came to a sharp point to complete the very picture of an elf. Elfin or human, she did not belong here.

‘Little girl, what’s your name.’ This was not phrased as a question, but as a demand.

‘Coco,’ she said, ‘like hot chocolate.’

How absurd. That would hardly fit a red-haired child, blue-eyed and so fair of face. ‘Where did you—’ Mrs Lanyard paused for a short scream when a rat ran close to the toes of her shoes. Impossible.

Inconceivable

. There was no mention of rats in her field guide – only birds and squirrels and banished sheep. She resolved to write the publishers immediately, and her criticism would be severe.

‘Urban rats are nocturnal creatures,’ said Coco, the faux camper, as if reciting from a field guide of her own. ‘They rarely venture out in daylight.’

Well, this was not the typical vocabulary of a child her age. The little poser might be the only gifted one in the lot. ‘So what about

that

rat?’ Mrs Lanyard pointed to the rodent slithering across the meadow. ‘I suppose he’s

retarded

?’

‘He’s a Norway rat,’ said Coco. ‘They’re also called brown rats, and they’re brilliant. They won the rat wars a hundred years ago . . . when they

ate

all the black rats.’ This bit of trivia was punctuated by ‘ooohs’ from the other children. Encouraged, the little girl went on. ‘They used to be boat rats. Now they live mostly on the ground. But some of them live in the sky, and sometimes it

rains

rats.’

In perfect unison, the day campers looked skyward, but no rodents were coming from that quarter. However, another rat was running toward them. Twenty-three pairs of eyes rounded with surprise. And one little boy wet his pants – finally. It never failed.

Oh, and there – another rat – and

another

one. Vile creatures.

In a wide swathe across the far side of the meadow, sun worshippers abandoned their towels to lope away, and screams could be heard at that distance where people and their vocals were only ant size. Dogs barked, and parents on the run madly piloted baby strollers in all directions.

Mrs Lanyard motioned for the children to gather around her. The little redheaded rat maven stepped out from behind the others and came forward, her thin arms outreaching, silently begging for hugs and comfort.