The Chalice (49 page)

Or walked into a tree and then staggered back into his bus.

Driven it into the woods because he couldn't see where the hell he was going.

None of the travellers they'd spoken to had admitted knowing him, but then they

wouldn't, would they? As for the false number plates on the bus, well, it was hard

to find any of these hippy wrecks with genuine plates.

'Was it his own bus?'

'I don't know,' Diane said. 'I haven't seen it.'

It would be easy to tell. If, for instance, there were yellow stripes

under some of the black. She'd been thinking a lot about the bizarre episode

with the girl, Hecate, and the children with their spray cans. Somebody had

told them to spray the bus black. To make it less conspicuous, less identifiable?

'I think the travellers killed him,' she said.

There'd been bad magic on the Tor that night. Colonel Pixhill

would have understood, would have recognised what she'd seen in the sky. And

again in the fire.

Powys was waiting for Diane

in reception, a styrofoam cup in his hand. In a baggy sweater and jeans, he

still looked a lot like his picture on the back of

The Old Golden Land,

although he must have been ever so young when

that came out. At school, other girls had photos of Tom Cruise in their

lockers; she dreamed about dishy J. M. Powys, earth-mysteries writer. How could

she not trust him now?

'How is she?' Powys asked.

'A little overwrought, I think. I didn't tell her you were here.

You don't mind, do you?'

He shook his head.

'There's a lot she isn't telling me,' Diane said. 'She keeps talking

about coming home, but I think she needs to get as much as possible out of her

system before she comes home.'

'You're a bit of a psychologist then, Diane?'

'I've been to enough,' she said.

He tossed his cup into a bin. 'I, um, meant in the Dion Fortune

sense.'

'Oh,' she said. 'Yes. I know what you're asking. The answer's

no. I've never had what you might call a practical involvement with the occult.

Never even been to a séance. Tried to take up meditation once, but I was

hopeless. I ... things just sort of happen to me.'

When they were back in the car, because he was J.M. Powys, who

dismissed nothing, she told him about the lightballs. About the Tor. And about the

Third Nanny.

'You saw her?'

'I didn't exactly

see

her. I was ... aware of her. Sitting on the edge of the bed.'

'And, um, what made you think this was Dion Fortune?'

'You're not going to put this in

your book, are you?'

'Not if you don't want me to.'

And he wouldn't. Of course

he wouldn't. He liked to think he'd gone way past the stage where books

mattered more than people.

All the same, she proved difficult to pin down on this one. At

first, she told him, she used to think she was a reincarnation of DF. But the

basis for this seemed to be little more than a teenage crush on the novels and

those initials.

(Powys didn't imagine Dan Frayne had any illusions about

his

initials.)

She wasn't quite sure when she'd first made a connection between

DF and the Third Nanny, who, to Powys, sounded suspiciously like a fantasy

figure to help her cope with life under the authority of the real ones.

'What happened to your mother?'

'She died when I was born. That is, I was born in rather a

hurry after she fell down the stairs at Bowermead.'

'I'm sorry.'

'My father's rather held it against me ever since. I don't think

he's ever been able to look at me without feeling a certain resentment.'

Powys thought this, and being brought up by starchy nannies,

was enough to disarrange any kid's psychology.

Several miles further on, somewhere down the M5, she said, 'It

isn't a coincidence.'

'No?'

'We were called back. You for John Cowper Powys, me for Dion

Fortune'

'Dion Fortune didn't have much time for JCP,' Powys pointed

out. 'She even misspelt his name.'

'That was deliberate A sort of smokescreen. If she didn't know

him well enough to spell his name right, she could hardly be involved with him

in a secret operation.'

'What secret operation was this exactly?'

'I don't know. But I think we have to find out. Why else have we

been brought back?'

'I haven't exactly been brought back. I've never been here

before. Also ...'

'You're a Powys.'

'I've been commissioned to write a book, Diane. That's all.

But it isn't all, is it?

Is her Third Nanny on the edge of the bed any more crazy than having your

living room repeatedly rearranged by a kinetic copy of

A Glastonbury

Romance?

Diane said, 'Do you believe in evil?'

'Probably. I mean, yes.'

'In Glastonbury?'

'Good as anywhere. Or as bad.'

'Colonel Pixhill believed in it very strongly at the end.'

'That's one very depressing book,' said Powys.

'People hate it in Glastonbury.'

'I can imagine they would. Doesn't fit the ethos.'

Diane said, 'There's an American called Dr Pelham Grainger,

who lives locally and apparently maintains that we don't let enough darkness into

our lives. I've taken over thirty orders for his book in the past fortnight.'

'I think somebody mentioned him a week or two ago. Sounds like

a very sick man.'

She nodded and stroked Arnold and didn't say anything else

until they were well past the Isle of Avalon sign.

'I've seen the Dark Chalice.'

Her voice seemed to reverberate, which didn't happen in Minis.

Powys slowed down drastically, the lights of Glastonbury all around them now.

There was a sort of shelter in the centre of the car park, under which Diane

had left the van.

Powys turned the Mini so that the

headlights lit up the side of the van.

He was waiting. This could mean almost anything; the Dark

Chalice seemed to be Pixhill's all purpose metaphor for bad shit.

'Oh no,' said Diane.

Although it wasn't yet nine p.m., the car park seemed completely

deserted It was another bright, sharp night, the moon not long past full, the

tower of St John's sticking up like a candlestick on the edge of a table.

Diane said. 'Oh, please ...'

He followed her eyes.

'Oh.' He got out.

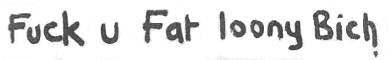

The back window of Diane's van had been smashed, so had the

driver's side window; glass all over the seat. Across the side panels, where

Diane had painted friendly pink spots there was uneven, black, spray paint

lettering, six inches high.

Diane stared at the van in

numbed silence. Powys squeezed her right hand with both of his. He saw the

black paint was glistening, still damp.

'It was in the fire,' Diane said tonelessly. 'When Jim died. That

was the second time, the first time was over the Tor. Like shadow hands holding

up a shadow cup. That was when I felt the evil. I've never felt anything like

it.'

'I'll call the police,' Powys said.

'No.'

'You can't just let them ...'

'The police are never going

to catch them. 'There's a garage I used to go to. I'll get them to take it away

first thing tomorrow.'

'Bastards.' Powys said. 'Have you any idea who might ... ?'

'It doesn't matter,' Diane cried. She turned away from the

van. 'It doesn't matter,' she whispered.

FOUR

Horrid Brown Fountain

Woolly said, 'Mind if I

move some of this stuff, Diane.' I need to spread the maps out.'

She put on all the shop lights; it was a dark morning. 'Gosh,

how many have you got?'

'Three. I need to put 'em all together. Think we're gonner

have to use the floor. This is heavy shit, Diane, man. This is, like,

end-of-the-world-scenario.'

Woolly squatted on the carpet and began to unfold an Ordnance

Survey map, sliding one edge under two legs of the display table for current

bestsellers. He'd phoned just after seven, to check if he could come round

before the shop opened. He needed to lay something on her. Couldn't believe

what he was seeing.

For once, Diane hadn't wanted to get up, not even for Woolly.

She'd been out long after midnight. Yes, OK, she'd lied to J. M. Powys. It did

matter about the van. It mattered terribly.

'I got the proof here, look, no hype,' Woolly said.

'Proof?'

'About the road. You all right, Diane?'

'Yes. Fine. Sorry. Go ahead.'

The maps were covered with little circles and ruler marks. All

Woolly's Ordnance maps were customised into ley-line plans, with prehistoric

sites - stones and burial mounds - and ancient churches, moats, beacon hills

and things neatly encircled in red ink. People like Woolly could prove all kinds

of wonderful things with maps and rulers and set-squares.

What you did was to find how many of the old sites fell into

straight lines and then draw them in. It never failed; you'd finish up with a

whole network of lines, some with four or five points, sometimes a whole

star-formation of lines radiating out from a single point, indicating a very powerful

ancient centre.

Glastonbury Tor, of course, was the classic example, perhaps the

most important power centre in the whole of Western Europe. Sure enough, there

it was on the second of Woolly's maps, with lines of force spraying out in all directions.

'Spent all night on this, Diane. Couldn't believe it myself at

first, where the road goes. Bit of a mind-blower, girl. Don't know how we

missed it, here of all places.'

Woolly was a very intelligent chap, but he'd done so many exotic

drugs in his time that he tended to approach life obliquely, from strange directions.

So that rather mundane things seemed, to him, quite astonishing.

Of course, there was the possibility that what Woolly saw was the

truth and everyone else was blinded by the familiarity of things. Diane liked

to think that, most of the time.

She made some tea. When she came back he had the three maps

pushed together, taking up more than half the shop. He was thumbing through one

of the paperback Dion Fortunes.

'Wish this lady was still around, Diane She'd get us organised

all right.'