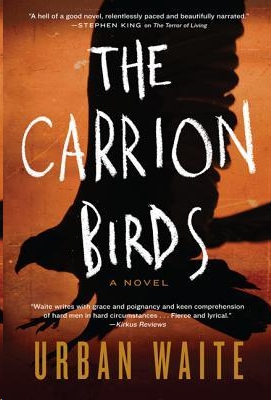

The Carrion Birds

Authors: Urban Waite

The Carrion Birds

Urban Waite

I wish that road had bent another way.

—

DANIEL WOODRELL,

Tomato Red

How terrible for a person to know what he could have been. How he could have gone on. But instead having to live along being nothing, and know he is just going to die and that’s the end of it.

—

OAKLEY HALL,

Warlock

T

he phone

woke Ray around three thirty in the morning. He lay there, eyes open. The

neighboring trailer lights casting a soft orange glow through the overhead

curtains and the smell of the night desert outside, ancient and scraped away,

through the sliding glass window.

Running a hand down his face, he could hear the

phone still. Wasn’t this what he’d asked for? Wasn’t this to be expected? He bit

at his lip, tasting the salt of dried sweat on his skin and feeling the pain as

he rubbed at his cheeks and tried to bring some life back into his face.

On the bedside table the phone was still ringing

and he put his hand out, searching. A series of empty beer cans tumbled to the

floor and he heard the soft patter of a can somewhere below that had been

half-full.

Too damn early.

He pushed himself up in bed, bringing the phone to

his lap, the receiver to his ear. He rested his back on the wall and waited.

“You ready to have some fun?” Memo said.

“Define ready.”

Memo’s voice cracked and Ray imagined the smirk

already formed on the man’s face. “I thought all you old guys woke before the

sun came up.”

“I’m not one of those ‘old guys,’ ” Ray said.

“Relax,” Memo said. “It’s a compliment.”

“Yeah? Define compliment.”

“It’s going to be just like the old days,” Memo

said.

“I hope it isn’t.”

The line went quiet for a moment, then Memo said,

“I called to let you know the kid is on his way. Let’s let bygones be

bygones.”

Ray sounded out the syllables. “

By-gones

.”

“Listen,” Memo said. “He’s my nephew and he looks

up to you. He’s the future around here so try not to get him killed.” Memo’s

nephew was Jim Sanchez. He was a kid to Ray, just out on parole after five years

away. Ray with no real idea what to expect.

“I never said I’d babysit.”

“You also said you’d never work for us again.”

“Things change.”

“Yes, they do,” Memo said, then he hung up.

Ray slid over and put the phone back on the bedside

table. Life hadn’t worked out the way he’d planned it would. The only reason

he’d agreed to work for Memo again was because the job was outside Coronado. It

was his hometown, a place where he’d married, had a son, and raised a family.

All that more than ten years ago, when he was in his late thirties. His life had

changed so much since then, since he’d taken the job with Memo. The round bump

just beginning to show on Marianne’s belly. No work anywhere in the valley and

Ray with a real need to put some money away.

Ten years and Ray hadn’t set foot in the place,

hadn’t even called home in all that time. A twelve-year-old son down there who

Ray feared wouldn’t even recognize him anymore. All this Ray had thought about

when Memo called, offering him the job, offering Ray a reason to go home, even

if Ray’s own reasons these last ten years had never been good enough. He owed

Memo that at least. Ray had wanted this for so long and never knew how to do it,

something so simple, a visit to see his son, a new life away from the violence

of the last ten years. Memo at the source of it all.

Memo had been a young man when Ray first met him.

Thin and muscular with the square Mexican features that later, after his

father’s death, began to round and cause Memo to appear as solid as a kitchen

appliance, his head now bald along the top and shaved clean as metal around the

sides and back.

Ray had liked the father more than he liked the

son, but it was Memo who had recognized the skill in Ray, and as Memo was

promoted up, so too was he. Ray was good at what he did, hurting people who

stood in the way of what Memo wanted. Enforcing the power of Memo’s family and

making sure the drugs they imported always reached their destination. But Ray

was careful, too, and he’d survived a long time by picking and choosing the jobs

that came his way.

Dark skinned, Ray had a shock of gray hair near

each of his temples and the round Mexican head that had been passed down from

his mother’s side, and that he’d grown used to seeing on his mother’s cousins

and brothers as he’d grown up. With his hair cut short the definition of his jaw

was more apparent, his features more pronounced where the coarse hair at his

chin came through in a patchy beard.

He raised his eyes to take in what he could of the

room, small and clogged with cast-off clothing. The back of his throat raw with

pain and tasting pure and simple as cleaning alcohol. The chalk-dry mouth that

went along with his drinking. Seven little dwarves climbing around in the back

of his head, ready to go to work, and just like that they did, rock chipping.

Miniature picks raised overhead, pounding away at the back of his skull in

unison, one after the other.

From the nightstand he took a bottle of Tylenol.

Cupped three of the pills in his hand and swallowed them dry, chasing them with

an antacid, followed a second later by one of the ten-milligram pills the doctor

at the VA had told him to take twice a day. The seven dwarves still chipping

away at the back of his skull, singing a child’s song he could only now draw up

out of memory, but that he’d once sung for his son. “Heigh-ho, heigh-ho, it’s

off to work we go.”

Ray ran the water in the sink. The single bathroom

light of a wall sconce shone yellow over his features. The mirror grown heavy

with steam, obscuring the round face that looked back at him.

He held a hand under the water, feeling the heat,

and then he brought the water to his face, letting it drip off his chin into the

sink basin. The throbbing in the back of his head receding, flowing back into

him little by little, medicine working, as if the men in there had gone

exploring down his brain stem.

He’d decided as soon as Memo had told him about the

job that it would be the last he would do. He was going home to Coronado. He was

going home to see his son. The money he’d saved would get him through the first

few years. He’d need to look for employment after that, perhaps even roughneck

in the oil fields again, but until then it would be enough. This last job would

help him with anything extra he needed.

In the years he’d been away he’d kept himself thin,

working away on the fat that appeared from time to time at the waist of his

pants or in the thighs of his jeans. Rigorously testing his muscles till the

sweat beaded and dampened his clothing. Still he’d gained weight over the years

since he’d left Coronado. What remained of the lean muscle appeared in the lines

of his brow and the slip of his mouth as he worked his jaw in front of the

mirror, lathering his face with shaving cream.

He was careful with the razor. Each pull of the

blade revealing the thin muddy brown of his skin, a mix of his father’s pink

tones and the darker skin of his mother. The deep cast of his face swept away

with the freshly shaven hair and his father’s thin, hawklike nose more

prominent.

Memo had said it was a shame what happened. Ray

didn’t know what to say about it. Nothing he could say would make the past go

away, bring Marianne back or cure his son, Billy. There wasn’t one thing Memo

could do, Ray knew this, knew how it worked, how the past didn’t change but the

future could.

Far out in the trailer park Ray heard a dog begin

to bark and then he heard the sound of gravel under tires. He checked his watch.

He went to the kitchen window in time to see the man he assumed was Memo’s

nephew, Sanchez, pull past in a Ford Bronco, brake lights coming on, dyeing the

kitchen blinds red as desert grit.

From the cabinet over the fridge he searched for

the cracker box with his gun hidden inside. The cabinet high enough that he

couldn’t see more than a few inches within and was forced to feel around in the

darkness above, bringing out box after box and then shoving them aside. Little

mementos of his former life hidden all over the trailer, tucked in beneath the

bench seat in the living room, shoved beneath the bathroom sink, out of sight

behind half-empty bottles of shampoo. All of them just small things—just what

he’d thought he could take with him, what he thought he might want sometime down

the road, but that he wanted nothing of now.

He stood looking at a box of Billy’s playthings,

knowing each and every item inside: a small plush toy, a plastic action figure,

a rubber bathtub duck. Everything inside, and even the smooth worn feel of the

box in his hand, a reminder of every reason he wanted out of this business and

hoped he’d never have to do it again.

This job was just a talk, Memo had said. Though Ray

knew it would be more. It would always be more. And he knew, too, that he was

out of time, and outside Memo’s nephew was waiting for him, waiting for him to

come out of the trailer and do this job.

Ray slid the toys back up into the cabinet. Finding

the box of Ritz, Ray removed the clear plastic bag with the stale orange

crackers inside and brought up the Ruger. The gun a dull metallic black,

unreflective under the kitchen lights, pieced back together and cleaned after

every use. He wrapped the pistol in his jacket before he heard the knock at the

door.

Sanchez stood there at the base of the trailer

stairs, his breath clouded around him in the air. Ray pushed the door aside and

walked out into the cold. He felt the air first, a dry forty degrees. Behind

Sanchez in the trailer park half-light, the Bronco sat with the driver’s door

left open and the thin drift of a Spanish music channel carried on the air. The

only other constants the bark of the dog far off toward the park entrance and

the shadowed bodies of the trailers like cast-off building blocks, scattered all

down the slim gravel road. Not a one of them the same, scraped and dented from

tenants who had come and gone and left their mark. Ray’s own trailer, an old

Dalton, rented out from the park for fifty dollars a week, rested there behind

him on wheels and cement blocks.

Ray watched how the kid moved, looking up at Ray’s

trailer like it was the first time he’d seen one and could hardly believe it.

Like Memo, he was Mexican, a few inches taller than Ray, young and thickly

muscled with his head shaved to the skin and a chin strap of black hair from one

ear to the other. Wearing a hooded sweatshirt and white tennis shoes.

“You the new blood?” Ray asked.

The boy stared up at him, a smile sneaking across

his face. “You the old?”

A

few

hours later Ray leaned back in the Bronco’s seat. The darkness of the locust

thicket wrapped all around, shadowing the shape of their vehicle from the dirt

road in front of them. The drive down from Las Cruces on the interstate had been

quiet. Twenty miles out Sanchez pulled over and let Ray drive. They headed south

toward the Mexican border, down a road Ray hadn’t been on for ten years.

Hardtop, cracked and filled with tar. Frozen in the high desert night and then

warmed through again in the day. Hundred-foot cement sections bouncing steady as

a heart beneath the springs. Scent of night flowers and dust in the cool desert

air.

Sitting there, Ray knew his life had been sliding

away from under him for a long time and today seemed like it would be no

exception. They’d driven almost two hours. At the end of it, after they’d pulled

up off the valley highway and found the dirt road running high on the bluff,

they sat watching as the sky slowly lightened in the east. No part of him

wanting to be here and only the solitary hope he held on to that the job would

be done soon enough, and with it the life he had followed for so long, for which

there seemed to be no cure.

There was a plan and he tried to think on this now.

He’d grown up working for his father in the Coronado oil fields, his shoulders

and arms carved from a daily routine that he continued still, doing push-ups on

the floor till his heart ached and his lungs pumped a fluid heat through his

bloodstream.

“My uncle told me you retired,” Sanchez said. The

slow tick of the engine in the morning air.

“I stopped working for Memo,” Ray said. He watched

Sanchez where he sat. The close cut of his hair outlining his thick eyebrows and

muscled Mexican face. “I didn’t retire, I just don’t work for your uncle

anymore.”

“You’re working for him now, though, aren’t

you?”

“I have my own reasons,” Ray said.

The Bronco had been stolen off a lot the night

before and fitted with a flasher box, wired directly into the headlights. A

spotlight bolted on just above the driver’s-side mirror, with a thin metal

handle that reached through a rubber glove into the interior of the cab. Sanchez

coming to get Ray in the night, before the sun ever crested the horizon. The

younger man wearing only a baggy set of jeans and a black sweatshirt against the

cold, the smell of tobacco and axle grease hanging thick around him.

Ray in the waxed canvas jacket he always wore. The

jacket padded to keep him warm. He wore a flannel shirt beneath, buttoned almost

to the collar, and an old worn pair of jeans, stained from other jobs and other

troubles, but worn regardless. The smell of sage and desert grit now floating up

through the vents as they sat talking, their eyes held forward on the murk of

the coming day. “I plan to move out of Las Cruces on this money,” Ray said.

“Where?” Sanchez laughed. “Florida? You’re not that

old and you should know you don’t retire from this line of work.” He brought out

a small bag of tobacco and some papers.

“This line of work?” Ray said.

“You know what I’m talking about.”

Ray told him he did. He knew a lot about what

Sanchez was talking about. Perhaps he knew too much. All he really wanted was a

way out, and he’d had it ten years before. Only he hadn’t taken it the way he

knew he should have. “You’ve been lucky,” Sanchez said, packing a cigarette.

“I have,” Ray said, agreeing. “I’ve tried not to

make mistakes.”

“The way I hear it from my uncle it was an

accident. But still, mistakes were made.”