The Cannabis Breeder's Bible (37 page)

Read The Cannabis Breeder's Bible Online

Authors: Greg Green

“Donkey ears” may also turn up in strains that have dense floral clusters and long internodes. That trait can be seen where a main cola develops spikes of floral clusters at its top or sides that are almost like miniature colas. They develop toward the end of the flowering cycle and are very noticeable a few days before harvest. Donkey ears are generally a sign of a good yielding strain. Jack Herer is famous for producing lots of donkey ears.

Calyx development occurs throughout the flowering period but will stop short between a few days and two weeks before harvest. During this time the profiles of the floral clusters will approach their final shapes. Calyx size is another trait to watch. A mature calyx can sometimes be as big 1/4 of an inch and even less than 1mm in size. As the plant goes through flowering, calyx development will continue in clusters. Sometimes the calyx development can be so large and clustered that it pushes leaves aside. This is a good sign of a strain that has a high calyx/leaf ratio. Sometimes a low calyx/leaf ratio will produce very fat and large calyx sizes that compensate for the leafiness of the bud, but these strains are in low numbers. This trait is generally found in very psychoactive Mostly Sativa strains and Indica/Sativa strains. Some strains have even mutated to produce abnormal or fused calyx development. It must also be noted that not all calyxes may be viable and produce pistils. Some plants produce very few pistils and instead produce an abundance of resinous and trichomes-covered calyxes. Other plants may produce very few calyxes with lots of resinous pistils, but either type can also be devoid of the presence of trichomes or resin because of breeding (something we do not want).

TRICHOMES AND BREEDING FOR CANNABINOID LEVELS

The same rules apply to flowers in regard to color as those discussed in the previous chapter, only note that the flower must not be treated as a whole—each individual part has its own color attributes. The “adaxial” (facing towards the stem) and “abaxial” (facing away from the stem) flowering parts, including the petioles, have different color attributes that can be crossed and stabilized because they are hereditary traits.

Cannabinoid levels refer mainly to the amounts of THC in the flowers (there are many other cannabinoid types, but THC is the one we are primarily concerned with as breeders). It is known that cannabinoid levels are very intricate and can vary a great deal even within stable strains. It is also known that hybrid results between strains of different cannabinoid quantities and types will produce a mean between the two, but this mean will be open to fluctuation because of the non-uniformity of a hybrid strain. The problem with cannabinoid level is that it is controlled by different genes and each one of the genes needs to be locked down in order to produce a strain that is uniform in cannabinoid production. The biggest problem in selecting for high type is the introduction of the ‘right’ male for the job. Since this is technically a ‘blind’ approach in breeding you will only be able to select a proper male parent for this trait through trial and error, but more controllably through test crossing.

When we are breeding for floral traits we need to use a male in the process that contributes to the traits we are really looking to carry through in the offspring. Since this is a hit or miss type of breeding, careful observation of the offspring must be made in order to know if the male you selected is the one that you need. Remember that a strain that is homozygous for a trait you are trying to perpetuate will also have that homozygous trait in both the male and female plants. The key is to find the homozygous male for that trait. This can only be done properly in a test cross, so when you are breeding for floral traits, be prepared to undertake quite a number of test crosses in your breeding project. You cannot depend on male leaf smoke for testing results because of possible placebo effects and the fact that female is what we want to really test.

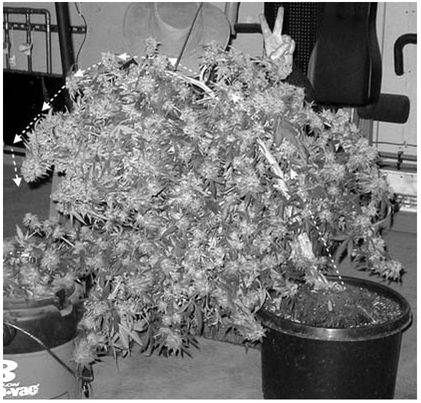

Breeder BOG bends a monster plant to reveal the fallen bud areas underneath. Those areas weigh a few ounces together. Top cola on the other end is about the size of an American football. In between the two ends is enough to keep you going for a long time. All from one plant. Optimal growth can be achieved by adopting the conditions set forth in

The Cannnabis Grow Bible

.

Obvious linked traits are taste and smell. These traits are not totally linked, but they do have much in common. A strain that smells skunky is going to taste skunky and a strain that smells fruity is going to taste fruity. What does change is the actual strength of each. We may have a very fruity smelling strain but the taste is masked by other traits in the bud’s chemical constituents. You may have a great smelling strain that does not have any taste. The smell trait is produced by the

terpenoids

(any of a class of volatile aromatic hydrocarbons with the formula c10h16 and typically of isoprenoid structure, many of which occur in essential plant oils), which are located in the resin secreted by the trichomes. The actual aroma we smell is caused when resin comes in contact with the air as a result of trichome fissuring on the surface of a pistil or a calyx.

There are well over 100 terpenoids that we can now readily identify in most cannabis strains and there are probably many more. This means that we have virtually unlimited space for aroma and taste development in cannabis plants. This is an area of breeding that is also very specialized and absolutely subtle. You must have very keen senses of smell and taste to be able to work with these traits.

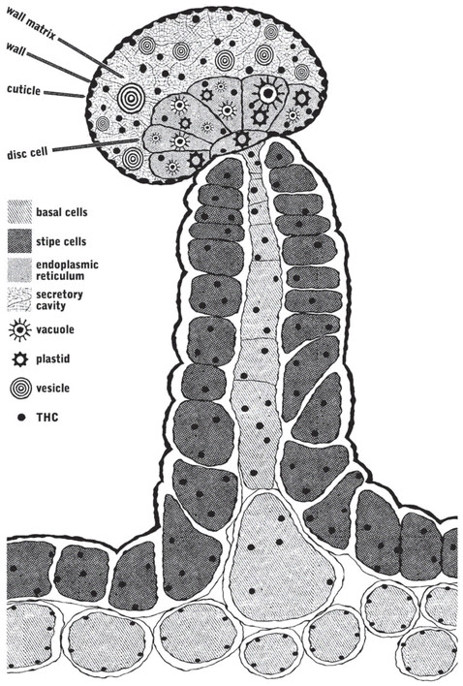

Trichomes also come in different types. They can be observed with a cheap 25x microscope, although stronger microscopes will give you better detail. The main type is the “glandular” trichome and this is subdivided down into “bulbous” tri-chomes, “capitate sessile” trichomes, “capitate stalked” trichomes and “simple” trichomes. Bulbous trichomes have a totally swollen look to them even at the start of their development. Capitate sessile trichomes do not appear to have a stalk but are rounded, extremely flat and closely clustered. Capitate stalked trichomes are the type most commonly found on cannabis plants. The trichome has three sections: the head, the stalk and the base. The effect is that of a rod with a bulb on the head, or as some might say, the mushroom look. Simple trichomes, which do not appear to have a head on the tip, generally do not produce much resin at all and are commonly found in low-resin-producing plants. There is a debate as to whether simple trichomes are in fact dysfunctional capitate stalked trichomes, but the trait can still be inherited and can produce good amounts of resin because resin production is not completely linked to trichome type and is a trait that can be bred through to future offspring. Trichome types can also be bred for vigor and strength, which is important for outdoor strains that may have to deal with harsh weather conditions. The flower may also terminate calyx development very early on. This type of termination is due to a trait that can be also be isolated by the breeder and bred much the same way we breed for flowering times. In general a mean is introduced between two strains that differ for this trait. Some strains like Afghani produce dense clusters of pistils that roll into balls as calyx development terminates. The remaining flowering time will concentrate mostly on resin production and pistil growth. The result is a rich content of resin being produced within the clusters. If a high resin production trait is not bred into this population then the remaining flowering time will just concentrate on pistil growth.

Anatomy of the cannabis trichome.

There are many theories as to why cannabis plants have trichomes and we can still only really guess why they are there. Probably the most obvious reason for trichome development is cannabinoid production. Man seems to enjoy the cannabis plant and has continued its propagation in many parts of the world, so man plays a major role in trichome development. Certainly mankind is an effective reason why the plant has kept producing trichomes and cannabinoids. Many insects and animals do not like cannabinoids. They find that the flowering female is too sticky to be near or the scent and taste puts them off—although there are still many other common insects and animals that thrive on cannabis. Cannabinoids appear to actually act as a good fungicide, preventing certain types of fungi and diseases from spreading too rapidly or occurring at all. A possible reason for cannabinoid development and trichomes can be found in the production of seeds. Even growers find it hard to remove the seeds from fresh bud without letting it dry out first, so trichomes offer a protective defense for the plant’s seeds. Trichomes are also very suitable pollen catchers. Female cannabis has been known to catch pollen from males that exist over a mile away. In the final stages of flowering, trichomes tend to catch more on fabrics. Growers have often walked into their grow rooms only to walk away with little pieces of seeded bud stuck to the tail end of their sweaters. This suggests that animals can trek over long distances with seeds attached to their coats.

There are many variations in floral presentation and the combinations are far from limited. Floral traits are the final expression of the overall quality of a cannabis plant. By the manipulation of colors, types, textures, flowering times, calyx production, resin production, aroma and taste we can create amazing floral displays that have a bite as well.

We have covered an intermediate description of cannabis anatomy. If you would like an advanced description of cannabis anatomy, you might want to pursue the study of full plant anatomy and its classification systems in depth.

20

ADVANCED BREEDING PRINCIPLES

WE HAVE DISCUSSED WHAT PLANT BREEDING IS, a bit about the relationship of plant breeding to other sciences, Darwinian evolution and evolution under domestication. We have focused on the mating systems of plants and their respective modes of reproduction. Genotype, phenotype, and the environment have been discussed, along with inheritance and heritability. Molecular genetics has been discussed on the basic level. We have included genetic diversity in this material including the breeding of self-pollinated plants. We have discussed pedigree methods of breeding as in the case of IBL development and the creation of hybrid strains.

You may still be wondering how all of this fits together. If you are still having trouble understanding, this chapter should help you to make sense of it all. If you have grasped the concepts that you have learned so far then this section will help to improve that knowledge and also stimulate some ideas of your own.

Plant breeding has evolved because it can be a science and or an art or even both. It is also important because humans are dependent on plants. We need plants in order to survive. One of the principle goals of plant breeding is to increase yields for our consumption. The second goal of breeding is quality.

“Cultivar” is a term used to describe a cultivated variety of a crop. Most domestic cannabis plants are cultivars. “Biotechnology” is the combination of science and technology to make use of our facts about living systems for realistic applications.

We have not seen much of the effects of biotechnology on a cannabis cultivar yet but undoubtedly someone soon will say that they will do it or have done it. Maybe genetically modified cannabis exists already in the market but we do not know about.

Genetically modified cannabis has not appeared on the scene at this time of writing.

Advancing plant genetics is just one part of improving crop productivity but we know that other factors contribute to our overall productivity. These include:

• genotype

• pest management

• seed condition