The Calendar (7 page)

There was also politics. From the beginning the Roman calendar, like most others, was a powerful political tool that governed religious holidays, festivals, market days, and a constantly changing schedule of days when it was

fas,

or legal, to conduct judicial and official business in the courts and government. (These

dies fasti,

or ‘right days’, gave the Roman calendar its name: the

fasti.)

In the early days of Rome the calendar and the all-important list of

dies fas

were controlled first by the Roman kings and then in the early days of the republic by the aristocratic patrician class. For the first several centuries after Romulus the priests and aristocrats kept the calendar a secret they shared only among themselves, which gave them a tremendous advantage over the merchants and ‘plebs’--commoners--in conducting business and controlling the elaborate structure of religious auguries and sacrifices that governed much of Roman life.

This monopoly on official time ended in 304 BC, when the plebs finally became so incensed that one of them, Cnaeus Flavius--the son of a freedman, who was later elected to several high offices--pilfered a copy of the codes that determined the calendar and posted it on a white tablet in the middle of the Roman Forum for all to see. After this the priests and patricians relented and issued the calendar as a public document--the first step in evolving the objective, secularized calendar that Caesar introduced two and a half centuries after Flavius’s theft.

But Flavius did not entirely win the day, for the patricians retained an important prerogative as the class from which Rome’s priests were drawn: control over when to insert intercalary months. It was this privilege that they abused so shamelessly for financial and political gain. Indeed, when Caesar returned home from Egypt and his other wars in 46 BC, he found that the many years of misuse had left the calendar in a shambles. Caesar himself was in part to blame, since he had held the title of chief priest--

pontifex maximus--

for several years, and had inserted an intercalated month into the calendar only once since 52 BC. This had left the Roman year to veer off the solar year by almost two full months. Whether this was an intentional manipulation by Caesar or his allies among the priests, or a simple oversight by a

pontifex maximus

distracted by civil war, is unknown. Whatever the cause, it played havoc not only with farmers and sailors but also with a population becoming more dependent than ever on trade, commerce, law and civil administration in a rapidly growing empire that desperately needed a standard system for measuring time.

To fix the calendar, says Plutarch, ‘Caesar called in the best philosophers and mathematicians of his time,’ including the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes, who seems to have come to Rome from Alexandria to fine-tune the reforms he and Caesar had discussed in Egypt. The core of the reform was identical to the system ordered by Ptolemy III in 238 BC--a year equalling 365 1/4 days, with the fraction being taken care of by running a cycle of three 365-day years followed by a ‘leap’ year of 366 days.

To bring the calendar back in alignment with the vernal equinox, which was supposed to occur by tradition on 25 March, Caesar also ordered two extra intercalary months added to 46 BC--consisting of 33 and 34 days inserted between November and December. Combined with an intercalary month already installed in February, the entire year of 46 BC ended up stretching an extraordinary 445 days. Caesar called it the

‘ultimus annus confusionis’,

‘the last year of confusion’. Everyone else called it simply ‘the Year of Confusion’, referring not just to the extended year but also to the heady whirlwind of change inaugurated by Caesar, who in effect was launching a vast new empire that already was profoundly reordering countless lives.

The extra days in 46 BC caused disruptions throughout the Roman world in everything from contracts to shipping schedules. The Roman historian Dio Cassius writes about a governor in Gaul who insisted that taxes be assessed for Caesar’s two extra months.

Cicero in Rome complained that his old political adversary Julius was not content with ruling the earth but also strove to rule the stars. Yet most Romans were relieved finally to have a stable and objective calendar--one based not on the whims of priests and kings, but on science.

To round out his calendar reforms, Caesar moved the first of the year from March to January, nearer to the winter solstice--an earlier calendar reform that had not always been adhered to. He then reorganized the lengths of the months to add in the ten days required to bring the year from 355 to 365 days, arranging them to create a calendar of 12 alternating 30-and 31-day months, with the exception of February, which under Caesar’s system had 29 days in a normal year and 30 in a leap year. He left the old calendar largely intact in terms of festivals and holidays. He also retained the old system of numbering days according to kalends, nones and ides, as well as the traditional names of the months, though later the Senate changed Quintilius to Julius (July) in his honour.

When the new day dawned on 1 January, 45 BC--the kalends of Januarius, 709 AUC--Romans awoke with a new calendar that was then among the most accurate in the world. Even so, it remained subject to errors and tinkering by priests and politicians. The first mistake was to come soon after Caesar’s death in 44 BC, when the college of pontiffs began counting leap years every three years instead of four. This quickly threw the calendar off again, though the error was easily corrected later by Emperor Augustus. Catching the mistake in 8 BC, he ordered the next three leap years to be skipped, restoring the calendar to its proper time by the year AD 8. Since that year this calendar has never missed a leap year--with the exception of those century leap years eliminated by Pope Gregory XIII in his calendar reform of 1582. But Augustus and his handpicked Senate did not stop with this sensible and necessary calendar fix. They also tampered with the length of the months, with results far less satisfactory.

This Augustan ‘reform’ began when the Senate decided to honour this emperor by renaming the month of Sextilis as Augustus. Part of the resolution passed by the Senate has been preserved:

‘Whereas the Emperor Augustus Caesar, in the month of Sextilis, was first admitted to the consulate, and thrice entered the city in triumph, and in the same month the legions, from the Janiculum, placed themselves under his auspices, and in the same month Egypt was brought under the authority of the Roman people, and in the same month an end was put to the civil wars; and whereas for these reasons the said month is, and has been, most fortunate to this empire, it is hereby decreed by the senate that the said month shall be called Augustus.’

This simple name change would have been fine. But either out of vanity or because his supporters demanded it, the Senate decided that Augustus’s new month, with only 30 days, should not have fewer days than the month honouring Julius Caesar, with 31 days. So a day was snatched from February, leaving it with only 28 days--29 in a leap year. To avoid having three months in a row with 31 days, Augustus and his supporters switched the lengths of September, October, November and December. This wrecked Caesar’s convenient system of alternating 30-and 31-day months, leaving us with that annoying old English ditty that seems to have originated in the sixteenth century, though it must have had precedents far more ancient:

Thirty days hath September,

April, June and November,

February has twenty-eight alone

All the rest have thirty-one.

Excepting leap year--that’s the time

When February’s days are twenty-nine.

Later Roman emperors would also try naming months after themselves. Nero, for instance, renamed April Neronius to commemorate his escape from an attempted assassination in that month during AD 65. Other month changes that failed to stick included substituting Claudius for May and Germanicus for June. When the Senate tried to change September to Tiberius, this taciturn emperor vetoed the measure, coyly asking: ‘What will you do when there are thirteen Caesars?’ In the provinces local leaders and subject kings frequently changed their months to flatter powerful figures of the moment. In Cyprus the calendar once had months named for Augustus; his nephew Agrippa; his wife, Livia; his half-sister, Octavia; his stepsons, Nero and Drusus; and even Aeneas, the legendary founder of Rome from whom Julius Caesar, Augustus and the entire Julian brood claimed to be descended.

The second error in Caesar’s calendar was less easy to repair than the mix up over whether a leap year came every third or fourth year. This was the conundrum noticed by the Alexandrian astronomers Hipparchus and Ptolemy and later by Roger Bacon and others in the Middle Ages--that Caesar’s year of 365 days and 6 hours ran slow. It’s likely that Caesar’s Egyptian advisor Sosigenes knew this too, though if he was familiar with Hipparchus’s calculation, no one mentions it.

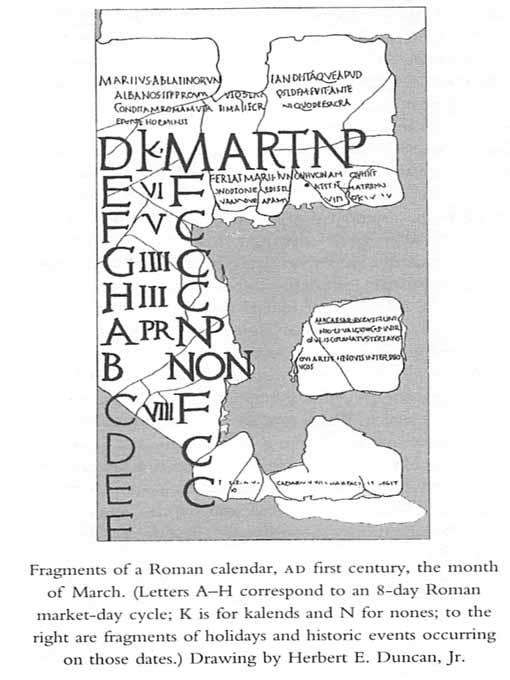

But even if Caesar was aware of a flaw amounting to a few minutes, it hardly would have upset him given the centuries that Romans had had to endure a calendric system that was frequently many days or months in error.* Indeed, after the initial grousing about the change, Caesar’s calendar became an object of pride for educated Romans. Excavations throughout the former empire have yielded calendars carved in stone and painted onto walls, much as we hang our calendars today.

*Romans had not yet invented the idea of a ‘minute’. They had a loose notion of an hour of the day; for astronomical purposes they divided up the day into simple fractions.

Caesar’s calendar also injected a new spirit into how people thought about time. Before, it had been thought of as a cycle of recurring natural events, or as an instrument of power. But no more. Now the calendar was available to everyone as a practical, objective tool to organize shipping schedules, grow crops, worship gods, plan marriages and send letters to friends. Combined with the rising popularity of sophisticated sundials and water clocks, the new Julian calendar introduced the concept of human beings ordering their own individual lives along a linear progression operating independent of the moon, the seasons and the gods.

Nothing symbolized this better than a public sundial erected in 10 BC by Augustus to commemorate his victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra, and to inaugurate his coming empire of peace. He used an obelisk transported from Egypt (which still stands in the Piazza del Popolo in modem Rome) as a 50-foot gnomon planted on the Campus Martius in the middle of an enormous grid of lines showing the length of hours, days and months, and the signs of the zodiac. Beside it was probably etched in stone a copy of Caesar’s calendar. ‘No one entering the Campus Martius could fail to see that the Caesars united heaven and earth,’ writes historian Arno Borst, ‘the Orient and the Western world, and the origin and evolution of time and history, or that they marked the beginning of a universal time.’

Not that every person in the empire suddenly abandoned their age-old calendars using the moon, stars and changes in the seasons. Only those who needed to measure time in the civic world of the empire did so. This excluded illiterate peasants, labourers and slaves who made up the vast majority of people living inside of Rome’s borders. Still, for the first time in European history the coming Pax Romana would foster a middle class of traders, bureaucrats, soldiers, lawyers, moneylenders and craftsmen who came in contact with the notion of measuring time using numbers and calculations.

4 A Flaming Cross of Gold

By the unanimous judgment of all, it has been decided that the most holy festival of Easter should be everywhere celebrated on one and the same day.

Constantine the Great, AD 325

Three and a half centuries after Caesar’s reform, Flavius Valerius Aurelius Constantinus stood on a bluff above the Tiber. Kneeling down in prayer he looked up in the sky and saw a flaming cross blazing above the sun. The cross was inscribed with three Greek words:

en toutoi niha,

‘in this sign conquer’. That night Constantinus, whom we know as Constantine the Great, dreamed he heard a voice as he slept amidst his army bivouacked north of Rome. The voice assured him victory in a battle to be fought the next day if he marked his standard with an X cut through with a line and curled around the top: the cross symbol of Jesus Christ.

At dawn on 27 October, AD 312, Constantine gave the order to paint the cross just before his legions attacked his chief rival at Saxa Rubra, Latin for ‘red rocks’. Brilliantly outmanoeuvring the forces of Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius, who had ruled Italy as co-emperor, Constantine pushed his enemy’s troops into the water near the Mulvian Bridge. Earlier Maxentius had foolishly breached this ancient stone causeway, thinking it would prevent his foe from crossing. Instead Maxentius drowned along with thousands of his legionnaires, leaving the road to Rome open to the 39-year-old victor and his cross-emblazoned legions.

Whether or not one believes Constantine about his visions--even the sycophantic court historian who later recorded them expressed his doubts--his victory at the Mulvian Bridge was a crushing personal triumph and a watershed moment for Europe precisely

because

he gave the credit to the Christian god. The West would never be the same. Nor would the way people thought about time and the calendar.