The Buried Pyramid (11 page)

“Ah. I wondered whether Fashion had made one of her radical turns once again. Certainly what I’ve heard about the new ‘aesthetic’ dress reminds me of the French court’s fashion for shepherdess costumes and simplified gowns not long before the French Revolution. Fashion always seems to return in some new version of itself.”

Neville smiled. Earlier that morning, Emily had come to him, anxious and upset, to report that Jenny’s trunks were packed tight with firearms, trousers, and other unladylike items. Emily seemed to think that Jenny might have somehow managed to sneak a male compatriot into Hawthorne House, and felt she must report the possibility.

Neville, familiar with Alice’s ongoing battles with her daughter over civilized dress, and his sister’s own musings over what was reasonable or logical given the Benet’s current area of residence, had been able to reassure the maid. He heard echoes of those mother/daughter debates in Jenny’s most recent comments, but had resolved not to raise the matter unless Jenny did so herself.

“Stephen possesses a colorful, if not completely creditable history—or I should say, his father did. The senior Stephen Holmboe came from money if not title. However, had he applied himself, I do not think a knighthood would have been out of reach for him. Such titles are more easily gained than you might imagine.”

Jenny raised a finger in interruption. “That reminds me. Did Herr Liebermann manage to acquire a knighthood for you?”

Neville shook his head, but his smile did not diminish.

“He did not. However, he did commend me to the queen’s attention. When some years later my deeds were such that my name was suggested for the awards list, the honor was quickly granted. I suspect that good Victoria did not forget her cousin’s request, even if it wasn’t appropriate at that time.”

“Ah,” Jenny said. “I didn’t think Mama said you’d been honored for saving some German, but in light of the rest of the story I thought you might have altered the report you wrote her. But were you saying that the elder Mr. Holmboe was not similarly honored?”

“Correct,” Neville replied. “Stephen’s father had wealth, physical robustness, intelligence, and an attractive person. However, he squandered these resources, alienated his wife and broke her health, and finally shot himself over unpaid gambling debts.”

“Goodness!” Jenny gasped. “How terrible for his son.”

“I believe these events scarred the boy—then nearly a young man—deeply. Some of Stephen’s foolish manner may be an effort to conceal that shame. He eschewed his father’s vices and from an early age became quite a scholar. There was not sufficient money both for books and for a fashionable wardrobe, so Stephen took to wearing his father’s clothes—he’d had a rather extensive wardrobe. Later, when styles changed, Stephen did not bother to have the clothes altered to a more modern cut. I think that Stephen’s defiance of fashion is also part of his continued rejection of the parental mold—though it could be he’s simply too absorbed in languages and history to care about the outer man.”

Jenny mused in silence for a moment. “And his mother? Does Mr. Holmboe have any siblings?”

“His mother is an invalid. He has two younger sisters as well. The first came out in a quiet way a few years ago and made a modest, though apparently happy, marriage. The second sister has not been so fortunate. She is bitter about her lack of suitors, and has loudly complained that her brother’s eccentricities have harmed her prospects. Having met her, however, I think she has no one to blame but herself—and perhaps her family’s lack of fortune.

“Mrs. Holmboe has a small income from a brother, who has otherwise distanced himself from her. I believe her elderly parents are even less kind. Stephen augments this income with what he earns tutoring and doing research for scholars of greater reputation.”

“Whew!” Jenny exclaimed. “I guess I can be patient with Mr. Holmboe, if he has had to put up with all of that. After all, there are worse things than dressing rather odd.”

“Mr. Holmboe was on his best behavior this afternoon,” Neville warned. “You have not seen my talented tutor at his most outré.”

“Well,” Jenny replied thoughtfully, “he hasn’t seen me at mine either.”

Neville thought she might be about to raise the question of attire, or perhaps of her collection of firearms, but though she paused, she said nothing and Neville kept his resolve to have her be the one to bring up these matters.

The following morning, Sir Neville found a dirty and tattered envelope mixed in with his morning post. His first impulse was to set it aside, believing that the butler had misdirected it when he sorted out the servants’ mail. On closer inspection, he saw that the envelope was addressed to him in a clumsy hand, with much blotting of ink.

He had just slit the envelope and unfolded the contents when the butler came to the door. “Mr. Stephen Holmboe, sir. He says he realizes that he has not made an appointment, but hopes that you would do him the honor of granting him a moment of your time.”

Neville suspected that Stephen had actually said something more like, “Morning, Weatherington. Is Sir Neville in? I just need a quick chat.”

“He would be very welcome indeed, Weatherington. Show him in directly.”

Perfect timing, Stephen,

Neville thought in amusement.

I wonder if he was outside waiting for the post to be delivered.

Stephen breezed in moments later. The portfolio tucked under one arm was the only neat thing about him. His golden whiskers were in disarray, and his clothing was subtly misaligned. Neville fancied that Stephen must have dressed in the dark, and the visitor’s first words confirmed that supposition.

“I had my final lesson with the Meadowbottom brat this morning. I don’t know which of us will be happier to see his lessons end. One thing’s sure, his father is going to hate losing my services. Won’t find anyone who’ll tolerate that imp of Set for less than twice what he was paying me.”

Neville made sympathetic noises, then pushed the letter across the desk.

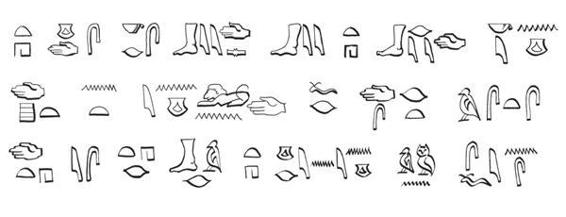

“I received your missive this morning,” he said with a chuckle. “Very clever. Haven’t had a chance to work it out though. You overestimate my skill—or at least how quickly Weatherington brings the letters around.”

Stephen had automatically picked up the sheet of paper, and was staring at it with what Neville could have sworn was genuine amazement.

“What are you talking about, Neville?” he asked, lapsing into the informality they had adopted during their teacher/student days. “I didn’t send this. Do you think I have the time for something this elaborate, what with everything to be finished before we depart?”

Neville wasn’t taken in.

“A letter in hieroglyphs? Come now. Who else would do something so elaborate? You must admit it’s right in line with your idea of a joke.”

Stephen raised his gaze from the letter. “I tell you, I didn’t do it. Moreover, it’s all wrong as a teaching exercise.”

“What do you mean?”

“No determinatives, for one,” Stephen said, frowning. “No syllabics, only the simplest phonetics . . .”

He trailed off, his gaze returning to the letter. Then he started, glanced around the clutter of the small room Neville used as an office, and said almost frantically:

“Neville, can we go into the library? I need to write something down and there’s no room in here. Do you still have those texts we used for your lessons?”

“Of course,” Neville said, leading the way across the hall to the library. “What’s wrong?”

“What’s wrong is more like what’s right,” Stephen said cryptic in his enthusiasm. “Wait just a moment or two and I’ll show you.”

They entered the library, and were halfway to the large, round table that stood invitingly in the morning sun, when they realized that Jenny was there before them. She had Mariette’s recent volume,

Itinéraire de la Haute Egypte,

open in front of her, and had been so absorbed in her reading that she hadn’t noticed them any more than they had noticed her.

“Uncle Neville. Mr. Holmboe. What is going on?”

Neville might have tried to distract her, but Stephen felt no such compunctions.

“Look at what came in the post for your uncle this morning.”

“Why it’s written in hieroglyphics,” Jenny said in astonishment.

“Hieroglyphs,” Stephen corrected absently, rummaging where he knew blank paper and pens were kept. “You wouldn’t call the letters we use ‘alphabetics’—same principle.”

“Oh,” Jenny looked temporarily stunned, but recovered quickly.

“Why is someone writing to Uncle Neville in hieroglyphs?”

“That is what we’re about to find out,” Stephen said. “Mind if I sit? This is going to get tedious.”

“Of course I don’t mind,” Jenny said, making room next to her. “Sit here. Uncle Neville can have your other side. This way we can both see what you’re doing.”

Stephen dropped into the indicated seat without hesitation.

“Neville, before you join us, would you grab that basic text we used for your class?”

Neville had already taken the requested volume and several others from their places, and he set them on the table.

“Now,” he said, “what is this about the message being ‘all wrong’?”

“All wrong as a teaching exercise,” Stephen clarified. “That’s what I said. Look at what we have here.”

They did. Clusters of hieroglyphs were drawn with elegant perfection on the page.

Jenny frowned. “They look all right to me. I even recognize a few—that owl and that reclining lion.”

“They are correct,” Stephen said, “as far as they go. What is wrong is what is missing.”

“I’m terribly confused,” Jenny admitted. “Would you mind explaining?”

“What do you know about hieroglyphs?”

“That it was fancy picture writing,” Jenny said, hesitantly. “The ancient Egyptians didn’t have an alphabet. Instead they had hundreds and hundreds of pictures, and none of them meant the same thing.”

“Accurate as far as it goes,” Stephen said, and Neville recognized the pedantic note creeping into the younger man’s voice, “but only as far as it goes. Actually, the Egyptians did use the same sign for more than one thing. That owl is a good example. It could represent the bird, but it could also mean the sound we associate with the letter ‘M.’ ”

Jenny frowned. “If you say so, but I’d think it would be confusing.”

“No more than our silent letters, once you know the rules,” Stephen replied with a shrug. “Though it’s something of a miracle that anyone ever translated the system at all. It would have taken much longer without the Rosetta Stone.”

“That’s the one found by Napoleon’s expedition,” Jenny said, “the one with the same text in a bunch of different languages.”

“Right.” Stephen waved a dismissive hand. “You can read about the Frenchman Champollion, and how the Rosetta Stone was the key to his discoveries and all the rest in a dozen books. What is important for our purposes here and now is a very odd fact. The Egyptians actually had a perfectly good alphabet. They just didn’t use it. Apparently, they preferred their cumbersome ideographs. Sometimes they even went to the trouble of writing redundant texts, including both the pictures and the phonetic signs.”

“Why?” Jenny asked.

“No one knows,” Stephen said. “Maybe they did it as a pronunciation guide. Egypt was a large and populous kingdom. Quite likely spoken Egyptian had dialects, just like modern English. Heaven knows, there are times I can’t understand what you Americans are saying.”