The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (58 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

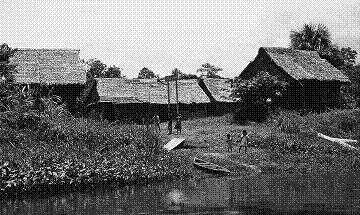

The village of Brillo Nuevo.

That night Nada, Moondancer, Terence, and I all took mushrooms in our guest house. Wade, Etta, and Don took a pass, as did Juan, our faithful but taciturn and ever-enigmatic guide. It was a quiet but strong trip. The next day, Terence, feeling peaceful and renewed, pronounced it “the trip I came here to have.” This bugged me. I wasn’t so sure it was the trip

I

had come to have. It started out typically enough with the usual efflorescence of hallucinations, but then I was plunged into a dark and depressing place. I felt my many longstanding grudges against Terence bubbling up, and was surprised by my anger and resentment. The events of the last weeks, the rejection letter from Sheila, the weird interpersonal dynamics of the Heraclitistas, Terence’s provocative behavior, my old childhood jealousies—all of this coagulated into a toxic knot of resentment in my gut. It was not a pleasant experience or a particularly useful one.

Days later, as we slowly made our way back upriver to Iquitos, I reflected on this:

23 March

My trip…became very introspective and depressing. I found myself wondering what in God’s earth had motivated me to come here, why I had sacrificed the woman I love to come to this hell hole in search of…what? I had the feeling that the work I am trying to do…is of no possible significance to anyone, not even myself. Particularly myself in view of what I have lost in order to do this thing…. I found myself feeling great resentment toward Terry in this regard…. He is already talking about my thesis and how great it is going to be, as though he had written it. In his mind, he regards it as already done. Easy for him—he is not looking at two to three more years of continued poverty and loneliness in order to make it a reality—a reality from which he will undoubtedly benefit as much or more than I. These feelings are not quite as strong now, in the light of two days away from the trip that precipitated them. Still, there is food for thought here and some points that would bear discussion…perhaps if we get a chance to travel alone we can talk about them.

If I was feeling conflicted, I was not alone. Since we’d achieved the goals of our expedition ahead of time, thanks to our lucky break in collecting

cumala

specimens and the paste preparations, we decided to head back to Iquitos earlier than planned. For most urbanized outsiders, being in the jungle for any length of time is uncomfortable, no matter how favorable the weather or the circumstances, and the environment was beginning to take its toll on us. Terence aptly observed that we were like infectious microbes injected into the circulation. As soon as the barrier is breached the invader is attacked by swarms of macrophages that start to nibble away, slowly tearing it apart piece by piece. And we’d only been in the field for a couple of weeks. Ours was an unlikely group to have been thrown together. Far more wearing than the physical discomforts were the tensions that seemed to be infecting our little band. Those we’d brought with us; and in close quarters and under stress, they’d festered. Why is it usually the psychodynamics that tend to undermine these efforts and turn them into misadventures? Maybe that’s what the Heraclitistas and the Biospherians were really studying. In the end, human beings are ornery, recalcitrant, and screwed up; and whether or not one takes psychedelics has little influence on that.

Writing in my notebook as we made our way back to Iquitos, I could feel the tensions of our strange interlude lifting somewhat. It was clear to me that another two or three weeks in that hostile environment would have broken us in health and spirit. Looking around, I could see I wasn’t the only one with private worries and pressures. Wade had been under stress, concerned about the course of his scientific career, the choices before him, dealing with his girlfriend. He’d certainly had enough of us. Nada and Moondancer were caught up in the peculiar life-structure of the community aboard the

Heraclitus

; they were with our party but not of it. Terence, thorny as usual, always the trickster, had his own idiosyncratic understanding of what we’d accomplished. Don seemed in better spirits, and who could blame him?

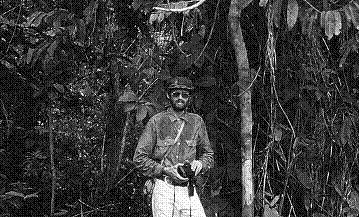

Terence standing beside a

cumala

tree near Puco Urquillo.

As I concluded in my journal entry that day, Iquitos and civilization would never look so good as it would when we arrived there in the morning.

Back in Iquitos, we spent the next few days recuperating, drying and processing specimens, sorting out the voucher samples we’d give to various institutions. I had contracted a serious chigger infection at Brillo Nuevo, and my legs were a mass of sores; I went on a regimen of tetracycline and hydrogen peroxide washes to control it. We had brought back fresh

Virola

seeds and live cuttings, and planted them temporarily at Adriana’s place until they could be dug up and prepared for transport. We reconnected with Nicole and spent a few pleasant evenings with her at Don Giovanni’s Italian Restaurant (those who are familiar with Iquitos today will know it as the site of the Yellow Rose of Texas, the current gringo watering hole in town). Nada and Moondancer returned to their berths and their shipmates on the Heraclitus; Wade was completely done, in every sense, with the Heraclitistas and with us, and he and Etta decided to move on to Lima. Don had separated himself from our group, pleading a desire to move into a cheaper hotel. It was as good an excuse as any.

Terence and I still had one mission to accomplish before he departed for California. By this time, we’d collected many tryptamine-containing specimens, but one important plant had eluded us:

chagropanga

, also called

oco-yagé

, the jaguar yagé, or spotted yagé. In ayahuasca, this plant was sometimes used in lieu of the common DMT admixture,

Psychotria

viridis.

In fact,

oco-yagé

was a liana in the same family as

Banisteriopsis

, the other key component in the brew, and at one time had been considered a

Banisteriopsis

species. Now properly known as

Diplopterys cabrerana

, this vine differs from

B. caapi

in that it doesn’t contain the MAO-inhibiting beta-carboline alkaloids that render DMT orally active. Rather, its leaves were apparently a source of DMT itself, and in staggering amounts—perhaps two or three times the levels found in

Psychotria

. In Ecuador, and in Colombia north of the Putumayo,

oco-yagé

was the admixture of choice, but most practitioners around Iquitos shunned it. In 1976, when Terence asked Don Fidel about this plant, he said he knew of it but dismissed it as “

muy bizarro

.” Yes, very bizarre: in other words, just what we were looking for.

Inquiries among our informants had come up dry. Terence and I wanted to get our hands on it so he could take cuttings back. We had one lead left; Tim Plowman had collected it in Tarapoto in the mid-seventies. He had given us a collection number and a specific location so we resolved to track it down.

The morning of April 7 found us 450 kilometers south of Iquitos, having just landed at the airport in Tarapoto. We checked into a hotel just off the Plaza de Armas, kicked back, smoked a little hash, and went off to explore the place. Tarapoto sat about 350 meters above sea level, and the higher altitude made it cooler than Iquitos. It seemed like a lovely little town, and I remarked in my notebook how much it reminded me of Kauai. We went immediately to the site where Tim had collected his

chagropanga

sample, Plowman 6041, nearly a decade earlier—a spot on the edge of town near the Río Shilcayo, a small stream running through a shallow valley dotted here and there with modest houses and gardens. Unfortunately, the collection site had been bulldozed years before and was now the site of a fancy tourist hotel.

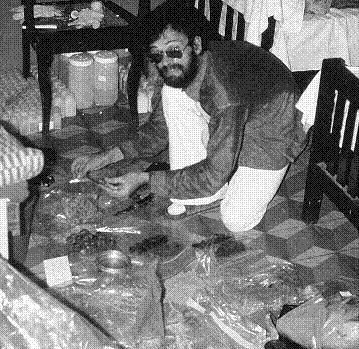

Terence packing seeds to take back to California, April 1981.

What to do? In similar situations, we’d found that if we went to the market and talked to the herb ladies, we’d quickly meet someone who knew about ayahuasca, or who knew someone else who knew. That’s how we’d met Don Fidel in Pucallpa. So we figured we’d give that a shot. The next morning we found every conceivable thing for sale at the crowded market

except

herbs. There were no herb ladies or herb stalls to be seen. Someone suggested we look up the owner of a bar where the

vegetalistas

hung out sometimes, and off we went.

Thus began a rambling search that lasted seven days. One inquiry led to another; every person sort of knew about what we wanted, but knew others who would certainly know. Sometimes, valuable discoveries occur while you’re looking for something else. In this case, it was the acquaintance of one Francisco Montes Shuña, the proprietor of a photo studio upstairs from a restaurant. A tall, thin man, Francisco was originally from Pucallpa; he said he knew Don Fidel. He suggested I look up his cousin when I returned to Pucallpa, a guy named Pablo Amaringo Shuña, an English teacher, painter, and musician.

Our eventual encounter with Pablo Amaringo would lead to a series of friendships and events that would play out over many years. Then unknown to the world, Pablo would later gain fame as a brilliant, self-taught painter of ayahuasca visions, thanks in part to my efforts and those of Luis Eduardo Luna. We “discovered” him and brought his work to the attention of a wider audience, a story I’ll save for another chapter. Francisco, Pablo’s cousin, turned out to be an excellent ethnobotanist and

ayahuasquero

, and I ended up working with him on my second trip to Peru in 1985. During the 1990s, Kat helped him establish an ethnobotanical garden outside Iquitos called the Jardín Etnobotánico Sachamama.

Back in Tarapoto in April 1981, however, we were focused on getting our hands on

chagropanga.

We learned it was known locally as “

puca-huasca,

” and not much about it beyond that. Though we never did find it, our quest brought us in contact with many interesting people, and a variety of plants and plant knowledge. We also got serious cases of dysentery after a grueling hike with some local informants. For the next two days, we lay wracked with diarrhea and abdominal cramps in our hotel room. It was all we could do to crawl to the toilet and back to the bed. We could barely muster up the energy to smoke hash, and that was all we wanted to do. Terence had thought to include a small bottle of laudanum (tincture of opium) in his medicine kit, so we alternated between smoking hashish and taking periodic droppers of opium. There is nothing better than opium for diarrhea, and I believe we would have been much worse off without it. The symptoms gradually faded, and we flew to Iquitos.

By then, Terence’s return to California was quickly approaching. Our recent confinement had only heightened the irritation I’d felt toward him since our time on the River of Poisons. Terence’s brusque way of dealing with the people we met in our search had begun to disturb me. I rankled at what I perceived to be his lack of respect as he seemed to verge on saying, “Just shut up and cough up the plant, already.” While I surely had some cause to be annoyed, I could sense my reaction was overblown. Why couldn’t I just shrug it off? As I knew even then, the psychological dynamics at play were far more interesting than my gripes. Once again, I turned to my notebook in an effort to make sense of the peculiar virulence of my reactions.