The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (40 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

By then, we’d taken the ayahuasca off the fire and set it aside, along with some bark shavings from the

Banisteriopsis

vine we’d used to make it. We planned to drink a small cup of the brew when we ate the mushrooms and, if necessary, smoke the bark to activate and synergize the psilocybin. Earlier, we’d gone to the pasture and located a beautiful specimen of

Psilocybe cubensis

and carried it back, intact and metabolizing on its cow-pie substrate. We had also collected several perfect specimens we’d eat to initiate the experiment. Though we hadn’t taken any for a couple of days, the mushroom “ESR” signal had been more or less audible to me ever since our last major session when I’d created the loud buzzing sound for the first time.

On the floor of the hut we drew a circle marked with the four cardinal points, and placed drawings of

I Ching

hexagrams at each one, to define and purify the sacred space where the work was to occur. Inside the circle, we placed the mushroom we’d chosen as our receiving template, along with the ayahuasca and the bark shavings. We suspended the chrysalis of a blue morpho butterfly near the circle so the metabolizing tryptamine from that source would be present. Why that of all things? We were attempting a kind of metamorphosis, and so clearly we needed a chrysalis close by. Kneeling together in the circle, each of us drank a small cup of the bitter brew, still slightly warm from its preparation. I munched two mushrooms, and we climbed into our hammocks to wait.

By then we were fully in the grip of the archetypal forces we’d activated. We were no longer in profane time or profane space; we were at the primordial moment, the first (and the last) moment of creation. We had moved ourselves to the center of the cosmos, that singularity point at which, as the Hermetic philosophers put it, “What is here is everywhere; what is not here is nowhere.” We were not in control any longer, if we ever had been. We were acting out our roles in an archetypal drama.

Though we were motionless, cocooned in hammocks in a hut in the Amazon, it felt as though we were approaching the edge of an event horizon. We could clearly perceive time dilating as we neared the moment of “hypercarbolation,” our term for the act of sonically triggering the 4-D transformation of the blended psilocybin and beta-carboline. Time was slowing down, becoming viscous as molasses as we fought against the temporal gale howling down from the future. “A series of discrete energy levels must be broken through in order to bond this thing,” I said. “It is part mythology, part psychology, part applied physics. Who knows? We will make three attempts before we break out of the experimental mode.

Who knew, indeed? We were following a script, but no longer a script we’d written. I ate one more mushroom and settled back into my hammock, wrapped in my poncho-like ruana. It didn’t take long before the mushroom’s energy began coursing through my body. I could hear the internal ESR tone getting stronger in my head; it had been easy to evoke, never far from perception for the last several days. I was ready to make the first attempt to charge the mushroom template.

I’ll let Terence take it from there:

Dennis then sat up in his hammock. I put out the candle, and he sounded his first howl of hypercarbolation. It was mechanical and loud, like a bull roarer, and it ended with a convulsive spasm that traveled throughout his body and landed him out of his hammock and onto the floor.

We lit the candle again only long enough to determine that everyone wanted to continue, and we agreed that Dennis’s next attempt should be made from a sitting position on the floor of the hut. This was done. Again a long, whirring yodel ensued, strange and unexpectedly mechanical each time it sounded.

I suggested a break before the third attempt, but Dennis was quite agitated and eager to “bring it through,” as he put it. We settled in for the third yell, and when it came it was like the others but lasted much longer and became much louder. Like an electric siren wailing over the still, jungle night, it went on and on, and when it finally died away, that too was like the dying away of a siren. Then, in the absolute darkness of our Amazon hut, there was silence, the silence of the transition from one world to another, the silence of the Ginnunga gap, that pivotal, yawning hesitation between one world age and the next of Norse mythology.

In that gap came the sound of the cock crowing at the mission. Three times his call came, clear but from afar, seeming to confirm us as actors on a stage, part of a dramatic contrivance. Dennis had said that if the experiment were successful the mushroom would be obliterated. The low temperature phenomena would explode the cellular material and what would be left would be a standing wave, a violet ring of light the size of the mushroom cap. That would be the holding mode of the lens, or the philosopher’s stone, or whatever it was. Then someone would take command of it—whose DNA it was, they would be it. It would be as if one had given birth to one’s own soul, one’s own DNA exteriorized as a kind of living fluid made of language. It would be a mind that could be seen and held in one’s hand. Indestructible. It would be a miniature universe, a monad, a part of space and time that magically has all of space and time condensed in it, including one’s own mind, a map of the cosmos so real that that it somehow

is

the cosmos, that was the rabbit he hoped to pull out of his hat that morning. (TH, pp. 108-109)

This didn’t happen, of course. Nor did a new universe emerge from the Ginnungagap, the “mighty gap” or abyss or void from which the universe emerged, according to Norse legend. The mushroom did not explode in a cloud of ice crystals as its DNA radically cooled, leaving a softly glowing, lens-shaped hologram humming a few inches above the floor of the hut. That did not happen because it

could

not happen; such an event would have violated the laws of physics. That didn’t bother us in the least—we were convinced we were about to overturn the constraints of conventional physics. Besides, we’d been getting feedback from the future; we knew that we were going to succeed because we already had! Yet what I had confidently predicted didn’t occur. What did? Terence again:

Dennis leaned toward the still whole mushroom standing in the raised experiment area.

“Look!”

As I followed his gaze, he raised his arm and across the fully expanded cap of the mushroom fell the shadow of his ruana. Clearly, but only for a moment, as the shadow bisected the glowing mushroom cap, I saw not a mature mushroom but a planet, the earth, lustrous and alive, blue and tan and dazzling white.

“It is our world.” Dennis’s voice was full of unfathomable emotions. I could only nod. I did not understand, but I saw it clearly, although my vision was only a thing of the moment.

“We have succeeded.” Dennis proclaimed. (TH, p. 109)

Succeeded at what? Not what I had predicted. But clearly

something

had happened. For one thing, I think we’d painted ourselves into a metaphysical corner. What I had predicted would happen, could not happen—

but we already knew that something would happen, because it already had!

I realize this statement suggests a misunderstanding of the nature of time, because how can something that was still in the future have already happened? Nevertheless, this is what we understood.

After the experiment, Terence was confused. I, on the other hand, thought I had the situation well in hand. As dawn neared, we left Ev in the hut and walked out to the pasture in silence, each lost in our own thoughts. I said something to Terence like, “Don’t be alarmed; a lot of archetypal things are going to start happening now.” And they did. That might have been the last coherent statement I would utter for the next two weeks.

By then I’d begun to disengage from reality, a condition that progressively worsened throughout the day. The reader may quip that we’d been thoroughly disengaged for quite some time, which might have been true; but even what grip I still had was slipping fast. As we stood in the pasture, Terence staring at me quizzically, I said, “You’re wondering if we succeeded?” What unfolded over the next few minutes was an episode of apparent telepathy. I could “hear” in my head what Terence was thinking. I was answering his questions before he articulated them, though with or without telepathy they were easy enough to anticipate. All of them were ways of asking, “What the hell just happened?”

But there was more to it than that. I felt I’d manifested a kind of internalized entity, an intelligence now inside me that had access to a cosmic database. I could hear and speak to this oracular presence. I could ask it questions—and get answers. As I explained to Terence, the oracle could be queried by prefacing the question with the name “Dennis.” For instance, “Dennis, what is the name of this plant?” And the oracle would instantly respond with a scientific name. Terence soon learned the oracle could also be addressed as “McKenna.” Something very peculiar was going on. Whatever it was, we were both under the thrall of the same delusion.

Shortly thereafter I lost my glasses, or rather, I hurled them into the jungle, along with my clothes, in one of my bouts of ecstasy. My blurred vision for the next few weeks surely playing into my estrangement from reality. When I tried to share our wondrous discovery with the others, they were underwhelmed. Vanessa, our resident skeptic, asked some mathematical questions of the oracle, and it was flummoxed, or it gave answers we couldn’t verify. Nevertheless, Terence and I were utterly convinced we had succeeded. We were sure that a wave of gnosis was sweeping the world with the advancing dawn line; people were waking up to find themselves, as Terence put it, “pushing off into a telepathic ocean whose name was that of its discoverer: Dennis McKenna.”

Chapter 32 - Waiting for the Stone

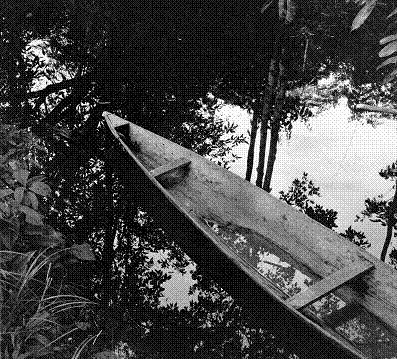

A canoe at La Chorrera. (Photo by S. Hartley)

The events at La Chorrera entered a new phase on our walk that morning in the pasture as we tried to sort out what had happened the night before. A full account of the following days would consist of three intertwined narratives. The first is the version told by Terence in

True Hallucinations

, written from the view of a participant in a delusion who nevertheless remained oriented in time and place. The second is the one our companions might have told, had they chosen to, as observers who hadn’t been caught up in our bizarre ideations. The third narrative is what I alone experienced, fragmented though it is.

My story began with a tremendous journey outward. To the extent that there existed a precedent for what happened to me, I relate it to my DMT trip in Boulder months earlier when I felt my mind had been blown literally to the edges of the universe. Standing on the lawn that autumn night, I became one with everything; the boundaries of my self were those of the universe. And so it was as I progressively disengaged from reality over the first day after our experiment at La Chorrera. Once again I was smeared across the totality of space and time. Was I reliving that earlier experience, or having one like it? The question makes no sense. There is only one experience like that, and it is always the same one; it takes place in a moment that is all moments, and a place that is all places.

At any rate, I was back in that place, at that moment. And my reintegration started there as well. I began to “collapse,” or perhaps “recondense” is a better term, on what seemed roughly to be a twenty-four-hour cycle; and with each cycle I got that much closer to reintegrating my psychic structure. By the second day I had shrunk to the size of the galactic mega-cluster, and by the third day to that of the local galactic cluster. I continued to condense at that rate down to the size of the galaxy, the solar system, the earth and all its life, the hominid species alone, my ancestral line, and then my family. The final distinction was between my brother and myself. Throughout this ordeal, I hadn’t been sure if we were separate entities or not. Once we had separated and I was “myself” again, it wasn’t the old self I had left. Like an ancient mariner returning home after a voyage of many years, I was changed forever. I was still resonating with the memories of those experiences, not fully reintegrated by a long shot, but I was grateful to be back in a body, back in a reality that conformed to my expectations—more or less, and most of the time.

But that took a couple of weeks. While I was lost on my shamanic journey, spiraling in closer and closer, Terence was engaged in his own reintegration, in a way that was complementary to mine. I was cruising through multiple spatial dimensions, whereas Terence was anchored in time; he was, in fact, the beacon I was following home. As we understood it, at the moment of hypercarbolation in our hut on March 4, we momentarily became one; then we split apart again, in a way that was analogous to the separation of a positive photographic plate from its negative image. We became temporal mirror images of each other. One of us, Terence, was moving forward in time, while I was moving backward in time, from the future. When both of us reached the point where past and future met, we would become fully ourselves again, except that by then we’d have fully integrated the experience of the other.