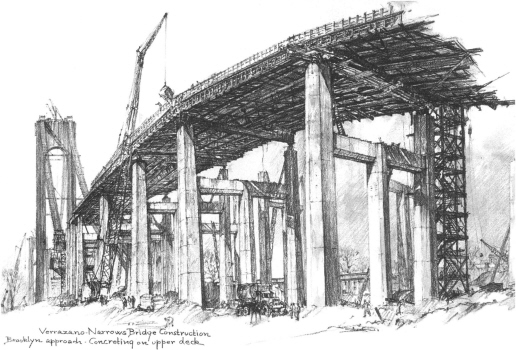

The Bridge (5 page)

Authors: Gay Talese

"I have been lucky," he said, quietly.

"Lucky!" snapped his wife, who attributes his success solely to his superior mind.

"Lucky," he repeated, silencing her with his soft, hard tone of authority.

Building a bridge is like combat; the language is of the barracks, and the men are organized along the lines of the noncommissioned

officers' caste. At the very bottom, comparable to the Army recruit, are the apprentices—called "punks." They climb catwalks

with buckets of bolts, learn through observation and turns on the tools, occasionally are sent down for coffee and water,

seldom hear thanks. Within two or three years, most punks have become full-fledged bridgemen, qualified to heat, catch, or

drive rivets; to raise, weld, or connect steel—but it is the last job, connecting the steel, that most captures their fancy.

The steel connectors stand highest on the bridge, their sweat taking minutes to hit the ground, and when the derricks hoist

up new steel, the connectors reach out and grab it with their hands, swing it into position, bang it with bolts and mallets,

link it temporarily to the steel already in place, and leave the rest to the riveting gangs.

Connecting steel is the closest thing to aerial art, except the men must build a new sky stage for each show, and that is

what makes it so dangerous—that and the fact that young connectors sometimes like to grandstand a bit, like to show the old

men how it is done, and so they sometimes swing on the cables too much, or stand on unconnected steel, or run across narrow

beams on windy days instead of straddling as they should—and sometimes they get so daring they die.

Once the steel is in place, riveting gangs move in to make it permanent. The fast, four-man riveting gangs are wondrous to

watch. They toss rivets around as gracefully as infielders, driving in more than a thousand a day, each man knowing the others'

moves, some having traveled together for years as a team. One man is called the "heater," and he sweats on the bridge all

day over a kind of barbecue pit of flaming coal, cooking rivets until they are red— but not so red that they will buckle or

blister. The heater must be a good cook, a chef, must think he is cooking sausages not rivets, because the other three men

in the riveting gang are very particular people.

Once the rivet is red, but not too red, the heater tong-tosses it fifty, or sixty, or seventy feet, a perfect strike to the

"catcher," who snares it out of the air with his metal mitt. Then the catcher relays the rivet to the third man, who stands

nearby and is called the "busker-up"—and who, with a long cylindrical tool named after the anatomical pride of a stud horse,

bucks the rivet into the prescribed hole and holds it there while the fourth man, the riveter, moves in from the other side

and begins to rattle his gun against the rivet's front end until the soft tip of the rivet has been flattened and made round

and full against the hole. When the rivet cools, it is as permanent as the bridge itself.

Each gang—whether it be a riveting gang, connecting gang or raising gang—is under the direct supervision of a foreman called

a "pusher." (One night in a Brooklyn bar, an Indian pusher named Mike Tarbell was arrested by two plainclothes men who had

overheard his occupation, and Tarbell was to spend three days in court and lose $175 in wages before convincing the judge

that he was not a pusher of dope, only of bridgemen.)

The pusher, like an Army corporal who is bucking for sergeant, drives his gang to be the best, the fastest, because he knows

that along the bridge other pushers are doing the same thing. They all know that the bridge company officials keep daily records

of the productivity of each gang. The officials know which gang lifted the most steel, drove the most rivets, spun the most

cable—and if the pusher is ambitious, wants to be promoted someday to a better job on the bridge, pushing is the only way.

But if he pushes too hard, resulting in accidents or death, then he is in trouble with the bridge company While the bridge

company encourages competition between gangs, because it wants to see the bridge finished fast, wants to see traffic jams

up there and hear the clink of coins at toll gates, it does not want any accidents or deaths to upset the schedule or get

into the newspapers or degrade the company's safety record with the insurance men. So the pusher is caught in the middle.

If he is not lucky, if there is death in his gang, he may be blamed and be dropped back into the gang himself, and another

workman will be promoted to pusher. But if he is lucky and his gang works fast and well, then he someday might become an assistant

superintendent on the bridge—a "walkin' boss."

The walkin' boss, of which there usually are four on a big bridge where four hundred or five hundred men are employed, commands

a section of the span. One walkin' boss may be in charge of the section between an anchorage and a tower, another from that

tower to the center of the span, a third from the center of the span to the other tower, the fourth from that tower to the

other anchorage— and all they do all day is walk up and down, up and down, strutting like gamecocks, a look of suspicion in

their eyes as they glance sideways to see that the pushers are pushing, the punks are punking, and the young steel connectors

are not behaving like acrobats on the cables.

The thing that concerns walkin' bosses most is that they impress the boss, who is the superintendent, and is comparable to

a top sergeant. The superintendent is usually the toughest, loudest, foulest-mouthed, best bridgeman on the whole job, and

he lets everybody know it. He usually spends most of his day at a headquarters shack built along the shore near the anchorage

of the bridge, there to communicate with the engineers, designers, and other white-collar officers from the bridge company.

The walkin' bosses up on the bridge represent him and keep him informed, but about two or three times a day the superintendent

will leave his shack and visit the bridge, and when he struts across the span the whole thing seems to stiffen. The men are

all heads down at work, the punks seem petrified.

The superintendent selected to supervise the construction of the span and the building of the cables for the Verrazano-Narrows

Bridge was a six-foot, fifty-nine-year-old, hot-tempered man named John Murphy, who, behind his back, was known as "Hard Nose"

or "Short Fuse."

He was a broad-shouldered and chesty man with a thin strong nose and jaw, with pale blue eyes and thinning white hair— but

the most distinguishing thing about him was his red face, a face so red that if he ever blushed, which he rarely did, nobody

would know it. The red hard face—the result of forty years' booming in the high wind and hot sun of a hundred bridges and

skyscrapers around America—gave Murphy the appearance of always being boiling mad at something, which he usually was.

He had been born, like so many boomers, in a small town without horizons—in this case, Rexton, a hamlet of three hundred in

New Brunswick, Canada. The flu epidemic that had swept through Rexton in the spring of 1919, when Murphy was sixteen years

old, killed his mother and father, an uncle and two cousins, and left him largely responsible for the support of his five

younger brothers and sisters. So he went to work driving timber in Maine, and, when that got slow, he moved down to Pennsylvania

and learned the bridge business, distinguishing himself as a steel connector because he was young and fearless. He was considered

one of the best connectors on the George Washington Bridge, which he worked on in 1930 and 1931, and since then he had gone

from one job to another, booming all the way up to Alaska to put a bridge across the Tanana River, and then back east again

on other bridges and buildings.

In 1959 he was the superintendent in charge of putting up the Pan Am, the fifty-nine-story skyscraper in mid-Manhattan, and

after that he was appointed to head the Verrazano job by the American Bridge Company, a division of United States Steel that

had the contract to put up the bridge's span and steel cables.

When Hard Nose Murphy arrived at the bridge site in the early spring of 1962, the long, undramatic, sloppy, yet so vital part

of bridge construction—the foundations—was finished, and the two 693-foot towers were rising.

The foundation construction for the two towers, done by J. Rich Steers, Inc., and the Frederick Snare Corporation, if not

an aesthetic operation that would appeal to the adventurers in high steel, nevertheless was a most difficult and challenging

task, because the two caissons sunk in the Narrows had been among the largest ever built. They were 229 feet long and 129

feet wide, and each had sixty-six circular dredging holes—each hole being seventeen feet in diameter— and, from a distance,

the concrete caissons looked like gigantic chunks of Swiss cheese.

Building the caisson that would support the pedestal which would in turn bear the foundation for the Staten Island tower had

required 47,000 cubic yards of concrete, and before it settled on firm sand 105 feet below the surface, 81,500 cubic yards

of muck and sand had to be lifted up through the dredging holes by clamshell buckets suspended from cranes. The caisson for

the Brooklyn tower had to be sunk to about 170 feet below sea level, had required 83,000 cubic yards of concrete, and 143,600

cubic yards of muck and sand had to be dredged up.

The foundations, the ones that anchor the bridge to Staten Island and Brooklyn, were concrete blocks the height of a ten-story

building, each triangular-shaped, and holding, within their hollows, all the ends of the cable strands that stretch across

the bridge. These two anchorages, built by The Arthur A. Johnson Corporation and Peter Kiewit Sons' Company, hold back the

240,000,000-pound pull of the bridge's four cables.

It had taken a little more than two years to complete the four foundations, and it had been a day-and-night grind, unappreciated

by sidewalk superintendents and, in fact, protested by two hundred Staten Islanders on March 29, 1961; they claimed, in a

petition presented to Richmond County District Attorney John M. Braisted, Jr., that the foundation construction between 6

P.M. and 6 A.M. was ruining the sleep of a thousand persons within a one-mile radius. In Brooklyn, the Bay Ridge neighborhood

also was cluttered with cranes and earth-moving equipment as work on the approachway to the bridge continued, and the people

still were hating Moses, and some had cried foul after he had awarded a $20,000,000 contract, without competitive bidding,

to a construction company that employs his son-in-law. All concerned in the transaction immediately denied there was anything

irregular about it.

But when Hard Nose Murphy arrived, things were getting better; the bridge was finally crawling up out of the water, and the

people had something to see—some visible justification for all the noise at night—and in the afternoons some old Brooklyn

men with nothing to do would line the shore watching the robin-red towers climb higher and higher.

The towers had been made in sections in steel plants and had been floated by barge to the bridge site. The Harris Structural

Steel Company had made the Brooklyn tower, while Bethlehem made the Staten Island tower—both to O. H. Ammann's specifications.

After the tower sections had arrived at the bridge site, they were lifted up by floating derricks anchored alongside the tower

piers. After the first three tiers of each tower leg had been locked into place, soaring at this point to about 120 feet,

the floating derricks were replaced by "creepers"-—derricks, each with a lifting capacity of more than one hundred tons, that

crept up the towers on tracks bolted to the sides of the tower legs. As the towers got higher, the creepers were raised until,

finally, the towers had reached their pinnacle of 693 feet.

While the construction of towers possesses the element of danger, it is not really much different from building a tall building

or an enormous lighthouse; after the third or fourth story is built, it is all the same the rest of the way up. The real art

and drama in bridge building begins after the towers are up; then the men have to reach out from these towers and begin to

stretch the cables and link the span over the sea.

This would be Murphy's problem, and as he sat in one of the Harris Company's boats on this morning in May 1962, idly watching

from the water as the Staten Island tower loomed up to its tenth tier, he was saying to one of the engineers in the boat,

"You know, every time I see a bridge in this stage, I can't help but think of all the problems we got coming next—all the

mistakes, all the cursing, all the goddamned sweat and the death we gotta go through to finish this thing . . ."

The engineer nodded, and then they both watched quietly again as the derricks, swelling at the veins, continued to hoist large

chunks of steel through the sky.