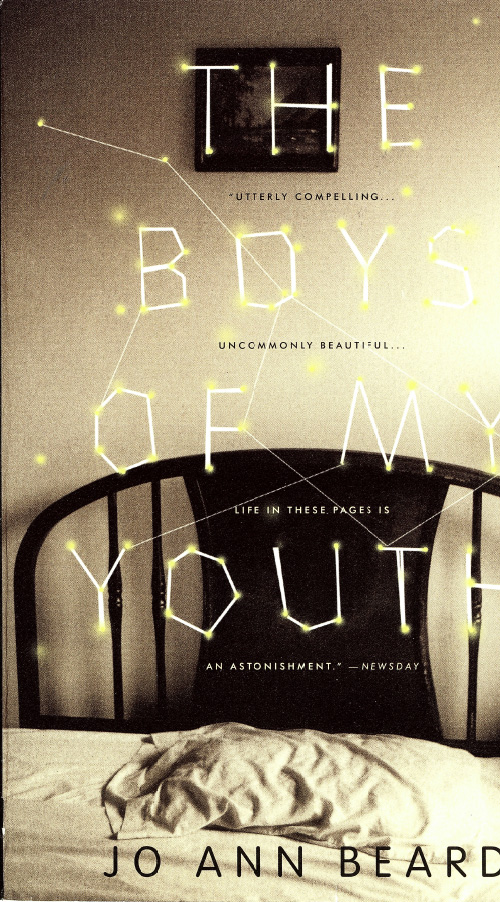

The Boys of My Youth

Read The Boys of My Youth Online

Authors: Jo Ann Beard

Copyright © 1998 by Jo Ann Beard

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Back Bay Books / Little, Brown and Company

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

Originally published in hardcover by Little, Brown and Company, 1998

First eBook Edition: November 2009

Back Bay Books is an imprint of Little, Brown and Company. The Back Bay Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book

Group USA, Inc.

The events described in these stories are real. Some characters are composites and some have been given fictitious names and

identifying characteristics in order to protect their anonymity.

“Coyotes” first appeared in

Story

; “Out There” and “Waiting” appeared in

Iowa Woman;

“Bonanza” appeared in

The Iowa Review

; “Cousins” appeared in

Prairie Schooner;

and “The Fourth State of Matter” appeared in

The New Yorker

.

The author is grateful for permission to include the following previously copyrighted material: Excerpts from “Over My Head”

by Christine McVie. Copyright © 1977 by Fleetwood Mac Music (BMI). Reprinted by permission of NEM Entertainment. Excerpts

from “Good Hearted Woman” by Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings. Copyright © 1971 by Full Nelson Music, Inc., and Songs of

Polygram International, Inc. All rights on behalf of Full Nelson Music, Inc., administered by Windswept Pacific Entertainment

Co. d/b/a Longitude Music Co. Reprinted by permission of Full Nelson Music, Inc., and songs of Polygram International, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-316-09186-2

for

B

RAD

and

L

INDA

Contents

Praise for Jo Ann Beard’s the Boys of My Youth

I

would like to express my gratitude

to the Corporation of Yaddo and the MacDowell Colony, for their generous gift of time, and the Constance Saltonstall Foundation

in Ithaca, for much-needed financial support. My sincere appreciation to Lizzie Grossman for her sustained belief in my writing,

her sanity, and her charming unwillingness to accept rejection when it came our way.

For their friendship, support, and encouragement, I offer profound thanks to Marilyn Abildskov, Mary Allen, Julene Bair, Charlie

Buck, Barbara Camillo, Martha Christiansen, Marian Clark, Tory Dent, Sara DiDonato, Ellen Fagg, Gaile Gallatin, Wesley Gibson,

Kathy Harris, Tony Hoagland, Will Jennings, Kathy Kiley, Carl Klaus, Edward Lawler, Jane and Michael O’Melia, Maxine Rodburg,

Corbin Sexton, Bob Shacochis, Kathy Siebenmann, Jo Southard, David Stern, Patricia Stevens, Shirley Tarbell, and that beloved

girl of my youth, Elizabeth White.

H

ere’s one of my pre-verbal

memories: I’m very little and I’m behind bars, like a baby monkey in a cage. My parents have just put me to bed in a room

with bright yellow walls. This is fine with me because in my crib there are various companions — the satin edge of my blue

blanket, the chewable plastic circle that hangs down almost to mouth level on a piece of green cord, and a boy doll named

Hal with blue eyes and lickable hands and feet made of vinyl. At this point in my life, I love Hal and the satin borders of

blankets better than I love any of the humans I know. My mother puts Hal up next to my head as soon as I lie down, which is

exactly where I don’t want him. I smack him in the face.

“You don’t want to hurt

Hal

,” my mother says sadly. “I thought Hal was your

friend

.”

Hal and I have an agreement that he isn’t supposed to come up by my pillow; if I want him I’ll go down to his end of the

crib. My mother snaps off the light and as she does so the night-light is illuminated, a new thing that I’ve never seen before.

The door closes.

I can see the night-light through the bars of my crib. It is a garish depiction of Mary and Joseph and Jesus, although I don’t

know that then. Jesus is about my age but he looks mean, and the mom and dad are wearing long coats and no shoes. All three

of them are staring at me funny. I start crying without taking my eyes off them.

The door opens and when the light goes on the night-light goes off. I stop crying and sit down by Hal while my mother looks

at me. She puts the blanket back over me and leaves. Light off, night-light back on. More crying. This time my father comes

in and picks me up, walks me around in a circle, puts me back in the crib with Hal, and leaves. When the light goes off and

Jesus comes back on I cry again. This time both of them come in to look at me. My mother is smoking a cigarette.

“Don’t ask me,” she tells my father.

About three more times and they give up. I am left to wail loudly, which I do for a while, until I happen to turn on my side,

looking for the bottle of water they had tried to bribe me with. As soon as I turn over the night-light miraculously disappears.

The water is warm, just how I like it, and Hal’s face is resting against the soles of my feet. I let go of the bottle and

wrap the satin border of the blue blanket around my thumb, put the thumb in my mouth, and close my eyes for the night.

I tried to check out that particular memory with my mother when I grew up. I asked her if she remembered a night when I cried

and cried, and couldn’t be consoled, and they kept coming in and going back out and nothing they did could help me.

“I don’t remember any that

weren’t

like that,” she said, smoking the same cigarette she’d been smoking for thirty years.

So. Here’s a recent memory, from two nights ago. I was riding through upstate New York on a dark blue highway, no particular

destination. It was cloudy, the air was springy and cool, the dashboard looked like the control panel of a spaceship. Piano

music on the tape deck, a charming guy in the driver’s seat. I thought to myself, not for the first time in this life,

Everything is perfect; all those things that I always think are so bad really aren’t bad at all

. Then I noticed that out my window the clouds had parted, the clear night sky was suddenly visible, and the moon — a garish

yellow disk against a dark wall — seemed to be looking at me funny.

T

he family vacation. Heat, flies

, sand, and dirt. My mother sweeps and complains, my father forever baits hooks and untangles lines. My younger brother has

brought along his imaginary friend, Charcoal, and my older sister has brought along a real-life majorette by the name of Nan.

My brother continually practices all-star wrestling moves on poor Charcoal. “I got him in a figure-four leg lock!” he will

call from the ground, propped up on one elbow, his legs twisted together. My sister and Nan wear leg makeup, white lipstick,

and say things about me in French. A river runs in front of our cabin, the color of bourbon, foamy at the banks, full of water

moccasins and doomed fish. I am ten. The only thing to do is sit on the dock and read, drink watered-down Pepsi, and squint.

No swimming allowed.

One afternoon three teenagers get caught in the current

while I watch. They come sweeping downstream, hollering and gurgling while I stand on the bank, forbidden to step into the

water, and stare at them. They are waving their arms.

I am embarrassed because teenagers are yelling at me. Within five seconds men are throwing off their shoes and diving from

the dock; my own dad gets hold of one girl and swims her back in. Black hair plastered to her neck, she throws up on the mud

about eight times before they carry her back to wherever she came from. One teenager is unconscious when they drag him out

and a guy pushes on his chest until a low fountain of water springs up out of his mouth and nose. That kid eventually walks

away on his own, but he’s crying. The third teenager lands a ways down the bank and comes walking by fifteen minutes later,

a grown-up on either side of him and a towel around his waist. His skin looks like Silly Putty.

“Oh man,” he says when he sees me. “I saw her go by about ninety miles an hour!” He stops and points at me. I just stand there,

embarrassed to be noticed by a teenager. I hope my shorts aren’t bagging out again. I put one hand in my pocket and slouch

sideways a little. “Man, I thought she was gonna be the last thing I ever seen!” he says, shaking his head.

The girl teenager had had on a swimming suit top with a built-in bra. I cross my arms nonchalantly across my chest and smile

at the teenage boy. He keeps walking and talking, the grown-ups supporting him and giving each other looks over the top of

his head. His legs are shaking like crazy. “I thought, Man oh man, that skinny little chick is gonna be the last thing

ever,”

he exclaims.

I look down. My shorts are bagging out.

M

y grandmother married a

guy named Ralph, about a year and a half after Pokey, my real grandfather, died of a stroke in the upstairs bedroom of Uncle

Rex’s house. At Grandma and Ralph’s wedding ceremony a man sang opera-style, which took the children by surprise and caused

an uproar among the grandchildren, who were barely able to sit still as it was. Afterward, there was white cake with white

frosting in the church basement, and bowls of peanuts. My mother and my aunts were quite upset about Grandma marrying Ralph

barely a year after their dad had died. They sat in clumps in the church basement, a few here, a few there, and ate their

cake while giving each other meaningful looks, shaking their heads ominously. My grandmother, a kind woman, was way above

reproach. So, it was all Ralph’s fault.

He took her to Florida on a honeymoon, a place where no

one in the family had ever been. There was an ocean there. They walked the beach morning and night, and Grandma brought home

shells. She divided them up evenly, put them in cigar boxes, and gave them to each of her thirty-five grandchildren. The cigar

boxes were painted flat white and glued to the top were pictures cut from greeting cards: a lamb, a big-eyed kitty, a bunch

of flowers. On that trip to Florida, I always imagine my grandmother walking in the foamy tide, picking up dead starfish,

while Ralph sat silently in a beach chair, not smiling at anyone.