The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind (6 page)

Read The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind Online

Authors: William Kamkwamba

“I thought I told you to leave me alone,” I said, then realized what I was doing. I couldn’t let anyone catch me talking to animals. They’d think I was mad.

Walking back from the toilet, I met Socrates coming out of our house with my father. He smiled and pointed at the dog now attached to my shadow.

“I see you found a friend,” he said. “You know, the good Lord blessed me with seven children, but they’re all girls. I think Khamba is happy to have found a pal.”

“I’m no friend to a dog,” I said.

Socrates laughed. “Tell that to him.”

A

FTER THAT,

I

GAVE

up trying to get rid of Khamba. It was no use. And to be honest, he wasn’t all that bad. Since I’d never had a dog of my own, it was nice having someone around, especially someone who didn’t talk or tell me what to do. Khamba slept outside my door each night, and when it rained, he’d sneak into my mother’s kitchen and curl himself in a corner. And without being told, he assumed his job as watchman over the goats and chickens, protecting them from the rare hyena or packs of mobile dogs that wandered wild and ate off the land. He also chased the goats through the compound, causing them to bleat and cry and kick up the dirt. When he did this, my mother would lean out of the kitchen and pitch one of her shoes at his head.

“Get that dog out of here!” she’d shout.

It was all a game to Khamba. He constantly tortured the chickens and guinea fowl, too, and even seemed amused when the mother hens flared their wings at him, hissing and giving chase.

But above all, what Khamba enjoyed most was hunting.

By this time, going hunting in the fields and

dambo

s began to replace many of the games I used to play at home. I’d started by tagging along with my older cousins like Geoffrey and Charity, who also lived nearby.

Mostly we hunted birds. We hid in the tall grass by the

dambo

s, which is so high during the dry season it can swallow a man whole. We’d wait until the afternoons when the birds came there to drink, then positioned a few sticks baited with

ulimbo,

a sticky sap that worked as a sort of glue. Once the birds stepped on the stick, they’d get caught and flap around, making all kinds of wild noises. Before they could break free, we’d jump out of the grass with our pangas, shouting:

“

Tonga!

I’ve got it!”

“Tamanga!

Get it fast, so you don’t scare off the others!”

“I’ll cut its throat!”

“No

—I want to pull off its head!”

We’d fight over who did the killing—usually taking turns cutting off the bird’s head, or holding it between our fingers and—

thop

—pulling it like a tomato. We’d clean the insides, remove the feathers, and store them inside sugar bags we slung around our necks. Once home, we’d make a fire and roast the birds on the red embers. Fortunately, our parents never made Geoffrey and I share our hunting meals, and some nights during summer, we’d come home with eight birds and have quite a feast.

My family never had much money, and trapping birds was often our only way of getting meat, which we considered a luxury. The Chichewa language even has a word,

nkhuli,

which means “a great hunger for meat.”

It wasn’t easy to satisfy this hunger, and sometimes these missions proved to be treacherous. For one thing, the best

ulimbo

sap for trapping birds came from the

nkhaze

tree, which grew very thick with branches covered with thorns. One had to squeeze inside the

nkhaze

with his panga and cut the trunk, being careful not to get the sap in his eyes. If he did, he went blind.

One afternoon, Charity, Geoffrey, and I were out looking for

ulimbo

when we spotted the perfect

nkhaze

tree.

“I’ll go!” said Charity. He was a kind of loud guy, who always wanted to be the leader. So we let him.

Charity climbed into the

nkhaze

tree with his knife, being careful of the sharp thorns all around. He reached up and sliced the trunk, then held a plastic sugar bag against the dripping wound. But just as he was doing this, a great gust of wind shook the entire tree, slinging the

ulimbo

into his eyes. Charity burst out of the bush, screaming, “I’m blind, I’m blind! Help me! It hurts!”

“What should we do?” I asked Geoffrey.

A man named Maxwell, who once worked for Uncle John, had taught us about the

nkhaze

tree and what to do if the sap ever got into our eyes.

Geoffrey turned to me. “You remember what Maxwell told us.”

“Yah,” I said. “What?”

“The only remedy is the milk from a mother.”

“Oh, where are we going to find that?”

“Your house.”

It was true, my mother had just recently given birth to my sister Mayless. Perhaps she could help. We guided Charity by the shirt and led him to my house. Once there, Geoffrey made our case to my mother, who happily agreed. She instructed Charity to kneel down and open his eyes. She took one breast from her shirt and leaned in close to his face.

“Hold still,” she said, and squeezed a stream of white milk into his eyes.

It was hilarious.

“Eh

man,” Geoffrey shouted. “Don’t get any in your mouth!”

“This is your payment for satisfying

nkhuli,”

I added, holding my ribs.

I never asked Charity how he felt about that incident, but I suppose it didn’t matter. Within minutes, he was able to open his eyes and see. We all agreed that Maxwell must be some kind of wizard for knowing this secret. My mother told Charity, “For my services, I get all the birds you kill on your next hunt.”

Charity agreed. The next day he brought four birds in a sugar sack and dropped them in the kitchen.

H

UNTING WITH MY COUSINS

had taught me the ways of the land: how to find the best spots in the tall grass and along the shimmering

dambo

pools, how to outwit the birds with a strong, smart trap, and the virtues of patience and silence when lying in wait. Any good hunter knows that patience is the key to success, and Khamba seemed to understand this as if he’d been hunting his entire life.

Our first outings began with the start of the rainy season, when the showers are heavy all morning and replaced in the afternoon by a sweltering, pasty air. When the land is wet and filled with puddles, the

dambo

s don’t attract as many birds. This is when we hunters rely on the

chikhwapu,

a giant deadly whip—or a kind of slingshot trap without the stone.

After the rains stopped one morning, Khamba and I set out to make our trap. I carried a sack on the end of my hoe made from a

mpango

—a kind of long, brightly colored scarf used by women to hold everything from their hair to babies on their backs. The sack contained a long bicycle tube, a broken bicycle spoke, a short section of steel wire I’d clipped off my mother’s clothesline, a handful of maize chaff we called

gaga,

and four heavy bricks. As always, I also carried the two hunting knives I’d made myself.

The first was a Rambo-style commando knife I’d made from thick iron sheets. First, I’d traced a fierce-looking pattern on the metal with a pencil. Using a nail and heavy wrench, I poked holes all along the lines, perforating the metal so it popped out with a good pounding. I then ground the metal against a flat rock to smooth the edges and produce a sharp blade. For a handle, I wrapped the bottom of the blade in enough plastic

jumbo

s to get a full, even grip. Then I melted the handle over a fire.

My second knife was more like a stabbing tool made from a large nail I’d pounded flat with the wrench and ground to a sharp edge. I’d fashioned its handle in the same way as the first. I kept both knives tucked snugly in the waistband of my trousers.

Packing my gear, I set off with Khamba down the trail behind Geof

frey’s house that led to the graveyard, down into the blue gums where the trees were taller and provided good shade. The hills of the Dowa Highlands—which separated us from the lake—rose beautifully before me, capped in gray, dripping thunderheads. A new storm was on its way, so we had to work quickly.

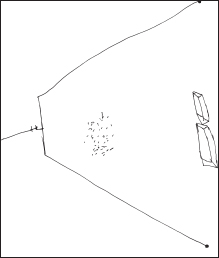

The view of the Dowa Highlands from my home. The mountains lie just beyond the maize rows and blue gum forest where Khamba and I would hunt.

Photographs courtesy of Bryan Mealer

I found a good spot off the main trail, near a tall blue gum that would cast a long shadow once the sun broke through the haze. Using my hoe, I cleared away the grass and vines until the red mud was exposed—a surface of about four feet in diameter. Taking my knife, I sawed off two thick branches from the blue gum and stripped their bark, then whittled both to sharp points. I pushed the poles into the moist soil about two feet apart, then pulled them to test their firmness. They held.

I cut the bicycle tube into two thin strips and attached both pieces to the section of steel wire. I then tied the rubber strips to the blue gum poles. When finished, it resembled a giant slingshot with a thick steel center. This was the kill bit.

Stripping bark off several nearby trees and lashing it together, I fashioned a long rope about fifteen feet long. I then cut a small, eight-inch section off it and attached it to the steel bit. I tied a short stick to the other end, making the knot fat and round. Gripping the stick like a handle, I pulled back the rubber bands as far as they’d stretch, then wedged the handle between two posts—a second stick and the bike spoke—using the fat, round knot to hold it in place. The long rope then led back into the trees and acted as the trigger. Once it was set, I stacked the four bricks several inches in front of the trap, then sprinkled the maize chaff in the middle. This was the kill zone. When the birds landed to eat the chaff, I’d pull the rope and release the sling, slamming the birds into the wall of bricks.

“Let’s hunt,” I said, and Khamba followed me into the trees.

The

chikhwapu

trap used to kill birds during the rainy season. The birds smashed into the bricks and died. Then I ate them.

We hid behind a small

thombozi

tree that allowed me to see clearly without being spotted. As soon as we got there, Khamba lay down beside me and stared keenly ahead. He never moved, never barked. After about half an hour, a small flock of four birds swooped over and spotted the bait. They fluttered down and began pecking at the dirt. My heart began to race. Khamba’s ears perked up and his mouth began to quiver. I was about to release the rope when I saw a fifth bird land just behind the others. It was giant, with a fat gray chest and yellow feathers.

Come on,

I thought,

a little more to the right. That’s it, come on.

After a few long seconds, the fat bird nudged his way into the group and started to feed. Once they were square in the kill zone, I pulled the rope.

WHOO-POP!

The birds disappeared in a cloud of feathers and chaff.

“Tonga!”

I shouted, and Khamba and I dashed out of our blind.

Four birds lay dead against the bricks, while a fifth had managed to fly away. The large bird was still flapping against the mud, so I picked it up before it revived. Its body was warm and soft in my hands. I could feel its tiny heart fluttering against my palm. I pinched its head between my two fingers and twisted its neck.

I picked up the others and dusted off the mud. Normally I’d carry a sugar bag, but today I’d forgotten. I stuffed the limp birds into my pockets.

Once the trap was reset, I waited for another half hour, then finally gave up.

“It’s time to eat,” I said.

Khamba and I then set off for

mphala.

M

PHALA

MEANS “A HOME

for unmarried boys,” which is exactly where my cousin Charity lived. It was more like a clubhouse, situated on our property just across from Geoffrey’s house. James, the seasonal worker who’d fought Phiri, had once lived there. But after he’d been laid off, it remained empty. Charity had taken over the house with his friend Mizeck, a big fat guy who’d dropped out of school and now worked as a trader. Although they both still lived with their parents—Charity’s house was near Gilbert’s in the blue gum grove—they slept at the clubhouse at night.