The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind (17 page)

Read The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind Online

Authors: William Kamkwamba

It explained how Archimedes used his “Death Ray”—which was really a lot of mirrors—to reflect the sun onto the enemy ships until, one by one, they caught fire and sank. That was an example of how you can use the sun to produce energy.

Just like with the sun, windmills could also be used to generate power.

“People throughout Europe and the Middle East used windmills for pumping water and grinding grain,” it said. “When many wind machines are grouped together in wind farms, they can generate as much electricity as a power plant.”

Suddenly it all snapped together. The blades on these windmills were driven by the wind, much like our toys. In my mind I saw the dynamo, saw myself with the neighbor’s bicycle those many nights ago, spinning the pedals so I could listen to the radio, thinking,

What can spin the pedals for me so I can dance?

“The movement energy is provided by the rider,” the book had said, explaining the dynamo.

Yes, of course,

I thought,

and the rider is the wind!

The wind would spin the blades of the windmill, rotate the magnets in a dynamo, and create electricity. Attach a wire to the dynamo and you could power anything, especially a bulb. All I needed was a windmill, and then I could have lights. No more kerosene lamps that burned our eyes and

sent us gasping for breath. With a windmill, I could stay awake at night reading instead of going to bed at seven with the rest of Malawi.

But most important, a windmill could also rotate a pump for water and irrigation. Having just come out of the hunger—and with famine still affecting many parts of the country—the idea of a water pump now seemed incredibly necessary. If we hooked it up to our shallow well at home, a water pump could allow us to harvest twice a year. While the rest of Malawi went hungry during December and January, we’d be hauling in our second crop of maize. It meant no more watering tobacco nursery beds in the

dambo,

which broke your back and wasted time. A windmill and pump could also provide my family with a year-round garden where my mother could grow things like tomatoes, Irish potatoes, cabbage, mustards, and soybeans, both to eat and sell in the market.

No more skipping breakfast; no more dropping out of school. With a windmill, we’d finally release ourselves from the troubles of darkness and hunger. In Malawi, the wind was one of the few consistent things given to us by God, blowing in the treetops day and night. A windmill meant more than just power, it was freedom.

Standing there looking at this book, I decided I would build my own windmill. I’d never built anything like it before, but I knew if windmills existed on the cover of that book, it meant another person had built them. After looking at it that way, I felt confident I could build one, too.

I

COULD PICTURE THE

windmill I wanted to build, but before I attempted something that big, I wanted to experiment with a small model first. From studying the pictures in the book, I knew that in terms of materials, I’d need blades, a shaft and rotor, plus some wires, and something like a dynamo to generate electricity from the movement of the blades.

Geoffrey and I had used a regular water bottle for those pinwheels we’d made as kids, but now I’d need something stronger. I’d seen Mayless and Rose playing cricket with an empty plastic jar of Bodycare perfumed jelly, so I went and grabbed it. The jar was shaped like a round tub of mar

garine with a screw-top lid. It was perfect. Leaving the lid intact, I sawed off the bottom of the jar with a bow saw, then cut the sides into four large strips, then fanned them out into blades.

I poked a hole through the center of the lid and nailed it to one of the bamboo poles my father was saving for tobacco shelters. I planted the pole in the ground behind the kitchen. But the wind hardly moved this contraption at all because the blades were too short. I needed extensions.

The floors in our bathhouses often fill with water so we install PVC pipes to serve as a drain. Several years earlier, a bathhouse behind my aunt Chrissy’s place collapsed, and they simply built another one beside it. I knew there was a piece of pipe still buried under the bricks, and after twenty minutes of digging around, I managed to pull it free. I sawed off a long section of it, then cut it down the middle from top to bottom.

I stoked the fire in my mother’s kitchen, getting it very hot, then held the pipe over the coals. Soon it began to warp and blacken, becoming soft and easy to bend, like wet banana leaves. Before the plastic could cool, I placed it on the ground and pressed it flat with a piece of iron sheet. Using the saw, I then carved four blades, each one maybe twenty centimeters long.

I didn’t have a drill, so I had to make my own. First I heated a long nail in the fire, then drove it through a half a maize cob, creating a handle. I placed the nail back on the coals until it became red hot, then used it to bore holes into both sets of plastic blades. I then wired them together. I didn’t have any pliers, so I used two bicycle spokes to bend and tighten the wires on the blades. That’s when my mother came up behind me.

“What are you doing messing in my kitchen?” she said. “Get these toys out of here.”

I tried to explain about windmills and my plan to generate power, but all she saw were some pieces of plastic stuck to a bamboo stick.

“Even children do more sensible things,” she said. “Go help your father in the fields.”

“I’m building something.”

“Something what?”

“For the future.”

“I’ll tell

you

something about the future!”

It was pointless to explain. What I needed now was a bicycle dynamo or some kind of generator, and I had no idea where I was going to find such a thing.

F

OR TWO DAYS

I tried to figure out how I could get a dynamo. I knew I could buy one, but where would I get the money? A trader named Daud had one for sale in his hardware shop in the trading center. I’d seen it there in the months before the famine—it hung on a shelf, shiny and silver and wrapped in plastic. It was beautiful. I went back this time, and sure enough, there it was. Daud stood between us, dressed in his round Muslim hat and long robe. I tried my charm.

“Fine day, Mister Daud.”

“Yes, fine day.”

“Your family?”

“Oh fine, thank you.”

“How much for that dynamo behind you?”

“Five hundred.”

“Yes, but you see, I don’t have five hundred.”

He laughed. “You know how it works. Go find the money and come back. It will still be here. And if not, I can order another.”

I could get money by working

ganyu.

At the time, guys were making one hundred kwacha unloading trucks at CHiPiKU store, so I headed there. If I worked a whole week, I could have enough. I waited outside the store all morning and into the afternoon. The sun was dreadful, and I had no water. Finally the owner walked outside and saw me.

“Why are you standing here?” he said.

“Waiting for trucks.”

“Trucks come every day,” he said. “Except Monday.”

It was Monday.

T

HAT NIGHT AT HOME,

I hit upon another idea. The bicycle dynamo was the ideal generator for the bigger windmill I wanted to create, and at some point I’d have to work for the money to buy it. But for this experimental model, I could get by with using a much smaller generator, and I knew just where to find that.

I walked over to Geoffrey’s house and found him in his room.

“Eh, bambo,

do you remember where we put that International radio-cassette player?”

“Yah, it’s here someplace. Why?”

“I want to extract its motor and use it to generate electricity.”

“Electricity?”

“Yah, from a windmill.”

Every time Gilbert and I had visited the library, Geoffrey was too busy working the fields. He hadn’t been that interested in going anyway.

“We’re headed to the library,” we’d say. “Wanna go?”

“Go ahead,” he’d answer. “Waste your time.”

But now, when I told him my idea of building a windmill that would produce power—and then showed him what I’d built so far—he saw things differently.

“Cool! Where did you get such an idea?”

“The library.”

U

SING A FLATHEAD SCREWDRIVER

we’d hammered out of a bicycle spoke, I removed the screws from the International radio cover and tossed it aside. I removed the cassette deck, and behind it, I found the radio motor. It was half as long as my index finger and as round as a AA battery. A piece of metal stuck out from the top like a stem, attached to a small copper pulley wheel that hoisted a thin rubber belt.

I carefully extracted the motor. With some wire, I attached the motor

to the bamboo so the copper wheel and the Bodycare lid were locked together side by side like two gears. But when I spun the lid, it slipped against the copper wheel. I needed some friction to make them catch.

“What we need is some rubber,” I said.

“Where do we get it?”

“I don’t know.”

“What about the heel of a shoe?”

The rubber from our flip-flops was too spongy and not durable enough, otherwise we’d be set. Everyone wore those. We needed a different kind of rubber—the kind Geoffrey had mentioned that’s used on the durable rubber flats worn by many women in Malawi. But it wasn’t going to be easy to find those shoes. A company called Shore Rubber had been going through the villages collecting women’s old rubber shoes to recycle and make new ones. They were offering a half kilo of salt for each pair, so of course, most women were taking the deal. But this was the perfect rubber for my windmill, and I was determined to find some.

All day Geoffrey and I dug through the rubbish pits at his house, Aunt Chrissy’s house, Socrates’ house, and finally my house, looking for shoes. Finally, after hours spent rummaging through mango skins, groundnut shells, banana peels, Geoffrey held up a shoe. One shoe.

“Tonga!”

The black shoe had been buried for so long it was now gray and covered in a layer of dirt and muck.

“Good job, chap!” I said.

Using my iron-sheet knife, I carved a tiny O-shaped piece out of the rubber, small enough to slide over the motor’s copper wheel like a cap. This took me an hour. Once I’d pressed it on, the two gears caught just right and spun together.

The next step was to test the motor to see if it produced current. With Geoffrey spinning the blades by hand, I took the motor’s two wires and touched them to my tongue.

“Feel anything?” asked Geoffrey.

“Yah, tickles,” I said.

“Good.”

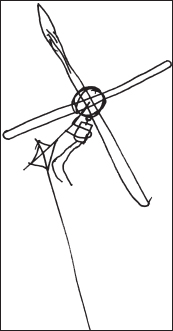

The first experimental radio windmill that I made with Geoffrey. The success of this model gave me the inspiration to go bigger.

Without stealing a radio from my father, the only functional radio we had was Geoffrey’s Panasonic, which he used when he was working in the fields. Geoffrey loved his Billy Kaunda music, and often I’d sneak up on him in the maize rows and catch him dancing.

I held the pole and fan in place while Geoffrey popped off the Panasonic’s battery cover and removed the cells. Without them, we’d need to connect the two wires to the battery’s positive and negative heads. Using my knowledge from the books, I assumed that because the radio operated on batteries, its motor produced DC power—unlike the dynamo on my father’s friend’s bicycle I’d played with months before, which produced AC power and only worked when connected to the radio’s AC plug.

“How do I know which head is positive or negative?” Geoffrey asked.

“If you connect the wires and hear music, you got the right one.”

“Whatever you say. Here it goes.”

He pushed the wires inside, then twisted them so they connected to the heads.

“What do we do now?” he asked.

“Now we wait for the wind.”

Then, just as I was saying that, the wind began to blow. My blades started to spin and the wheel began to turn. The radio began to pop and whistle, and suddenly there was

music!

It was my new favorite group, the Black Missionaries, on Radio Two, singing their great song, “We are chosen…just like Moses…”

I jumped up so high I nearly disconnected the wires.

“You hear that, man?”

I screamed. “We did it! It actually worked!”

“At last!” Geoffrey yelled out.

“Now I’ll go even bigger. Superpower!”

“Yah!”

W

ITH THAT LITTLE SUCCESS,

I started planning for an even bigger windmill.

That model had already revealed itself in my mind, so there was no need to draw it out. The picture was of a much larger machine, which still used PVC pipe as blades. For the rotor, I’d need some kind of strong, flat metal disk. For the shaft, I’d use the bottom bracket, or axle, of a bicycle—what we called the “gav”—that connected the crankset and allowed the sprocket, cranks, and pedals to rotate. My plan was to cut the entire crankset off a bike to reduce the size, while leaving the back wheel intact. The blades would somehow be attached to the gav and act as pedals. When the wind blew, the blades, sprocket, and chain would spin, rotating the back wheel, and turning the dynamo.