The Book of Honor (51 page)

A string of internal betrayals also shattered public confidence in the Agency. CIA officer Aldrich Ames's treachery is believed to have led to the execution of at least a dozen foreign agents who had served the Agency. The CIA's Douglas F. Groat attempted to blackmail the Agency, demanding $1 million in exchange for not disclosing how the United States intercepted foreign communications. Senior CIA officer Harold James Nicholson also sold out to Moscow. For all its obsessive secrecyâ indeed, perhaps because of itâthe CIA could not protect its most sensitive secrets. “If we guard our toothbrushes and diamonds with equal zeal,” once observed former national security adviser McGeorge Bundy, “we will lose fewer toothbrushes and more diamonds.” As if to prove that very point, even a former director of Central Intelligence, John M. Deutch, had to be stripped of his security clearance in the summer of 1999 after it was discovered that he had placed sensitive national secrets on his unsecured home computer.

Public trust of the Agency remains at a low point. Allegations in the press, no matter how spurious, implicate the Agency in the introduction of crack cocaine to South-Central Los Angeles.

In the midst of such turmoil the Agency is attempting to rebuild itself. Since 1991 thousands of its most experienced officers, a quarter of its workforce, have retired or quit. New recruits were suspect. Many seemed as concerned with benefits and retirement plans as service. Old hands in the clandestine ranks mused that they never assumed they would live long enough to enjoy such rewards. The Agency seemed rudderless, losing four directors in six years.

That was why George Tenet urged Agency employees at the memorial service to linger at the Wall of Honor, hoping that they might draw strength from the collective memory of the Agency's past. A year earlier the CIA had put in a reflecting pool and garden dedicated to those killed in service. But its real purpose was to offer a place of refuge to an increasingly troubled cadre of employees.

Ironically the secrecy that had failed to protect the Agency from Soviet penetration had prevented Americans from coming to terms with their own past. In 1995 President Bill Clinton vowed to declassify vast amounts of Cold War documents, but three years later the CIA reneged on its promise to release accounts of major operations from that very period. The State Department, too, chastised the Agency for withholding materials vital to America's diplomatic history. The U.S. Archives has next to nothing from the Agency, which seems bent on controlling what little of its history it chooses to reveal.

In the Agency's own archives are an estimated 65 million classified documents more than twenty-five years old. That same compulsive secrecy enshrouds the Book of Honor. Douglas S. Mackiernan was killed on the Tibetan border in 1950. His star remains nameless. So, too, does that of Hugh Francis Redmond, who died in 1970 after nineteen years in a Chinese prison. In both instances the Chinese knew they were CIA spies. Only the American public did not.

In Washington the demand for Agency reform grows. Some call for its dismantlement. But though the Cold War is over, it is not a safer world. In lieu of the Soviet Union, the CIA continues to monitor foreign powers hostile to the United States but also targets the four “counters”âinternational narcotics, crime, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, and terrorism. Its mandate is broader than ever; some would argue too broad to be effective.

But this was a day not for recriminations, but for remembering. Tenet completed his remarks and returned to his seat. “Would you please rise for the roll call?” asked Jack G. Downing, the CIA's spymaster. One by one, the names of those inscribed in the Book of Honor were read aloud:

Jerome P. Ginley, William P. Boteler, Howard Carey, Frank C. Grace, Wilburn S. Rose, Chiyoki Ikeda, Thomas “Pete” Ray, Riley Shamburger, Wade Gray, Leo Baker, John G. Merriman, Eugene Buster Edens, Edward Johnson, Mike Maloney, Louis A. O'Jibway, Walter Ray, Billy Jack Johnson, Jack Weeks, Paul C. Davis, David Konzelman, Wilbur Murray Greene, William E. Bennett, Richard Welch, James S. Rawlings, Robert C. Ames, Scott J. Van Lieshout, Curtis R. Wood, William F. Buckley, Richard Krobock, Lansing H. Bennett, Frank A. Darling, James Lewek, and John Celli.

They died in places far away and unnervingly close to homeâthe China Sea, Cyprus, Germany, Nevada, Indiana, Cuba, the Congo, Laos, Vietnam, China, Greece, Lebanon, El Salvador, Bosnia, Saudi Arabia. Lansing Bennett and Frank Darling had been cut down at the Agency's front gate in Langley, murdered on their morning commute by an AK-47-toting Pakistani named Aimil Kansi. The date was January 25, 1993.

Of the seventy-one stars, only thirty-three names were read aloud. The identities of the other thirty-eight remain classified.

Among those nameless stars is one representing Freddie Woodruff, who was shot to death in August 1993 in the former Soviet republic of Georgia. The forty-five-year-old son of a professor, he was an ordained minister who could read ancient Greek and speak Russian, German, Turkish, Armenian, and several other tongues. He had been in Georgia under cover as a political officer at the U.S. Embassy. His mission was to train the security force assigned to protect that nation's embattled leader, Eduard Shevardnadze.

Also unnamed was a young woman who died a violent and selfless death in 1996. An anonymous star in the Book of Honor, her name is withheld from this book. The Agency made a compelling case that to identify her would put others at risk.

After the reading of names, a wreath was set before the wall. Then came a moment of silence and, finally, the mournful sound of a trumpet playing “Taps.” When the last note had faded, it seemed that no one knew what to do next. Families fidgeted nervously, awaiting some cue. At last, someone took to the podium and indecorously declared “It's over,” and with that came an awkward laugh and a sigh of relief.

Afterward, some family members posed before the Wall of Honor as an Agency photographer took their pictures. Each person offered to give the photographer his or her name and address. But the photographer declined, smiling coyly. “We'll get them to you,” he said. “We know who you are.” In the past, some photographs arrived blurred or doctored so that individuals were not identifiable.

Following the ceremony, the families attended a brief reception on the upper lobby, sipping lemonade and nibbling on crackers and cubes of cheese, star fruits and grapes. Then the families went their separate ways.

Some went to the Agency museum and saw a tiny camera disguised as a matchbox, a walking cane that fired .22-caliber rounds, and an alarm clock once attached to a bomb that never went off. Its intended victims were CIA officers in the Mideast.

Others went to the employee store and bought souvenirsâa key chain, a shot glass, a paperweight, all bearing the Agency seal.

Many found time to walk along the gallery corridor pausing before the formal oil portraits of the Agency's past directors, each presented in a statesmanly pose. With pipe or spectacles in hand, these former directors looked almost infallible. These were the men in whom their loved ones had entrusted their lives. They were cordoned off by a velvet rope, their reputations only as secure as the secrets they kept.

Some family members planned to lunch together. They shared photographs and memories, exchanged addresses and phone numbers. On this day they could find some measure of relief, as if the silence to which they had been sentenced had been momentarily commuted.

Before leaving, most paused to take a final look at the Book of Honor, to press their finger against the glass, intone a silent prayer, or whisper a parting message to the star for which they had come so far.

Much of the story of the CIA is contained within these stars, but it is a story the Agency holds to itself. In the end the CIA and the families who gathered this day are both hostages to history. Whether the Agency will ever release its past and whether it will find for itself a meaningful future are both in some doubt. As from the beginning, the dilemmas it faces are not entirely of its own making. Those who daily enter the old headquarters lobby must still pass between the scriptural verse etched into the marbleâ“And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free”âand the cautionary Wall of Honor across from it. Between these two walls, between the values of an open society and the demands of a craft rooted in deception and betrayal, the CIA is asked to steer an uneasy, often irreconcilable course.

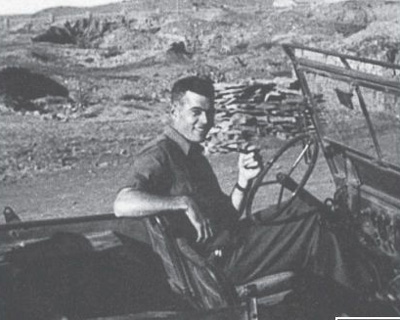

LEFT: CIA case officer Douglas S. Mackiernan in his jeep in China's far west province of Xinjiang, where he was stationed undercover as a low-level State Department employee.

(Courtesy

of Pegge Hlavacek)

BELOW: Douglas S. Mackiernan and wife Pegge in New York City's Central Park the winter of 1947â1948.

(Courtesy of Pegge Hlavacek)

Passport photo of Douglas S. Mackiernan, then working for the CIA undercover as a State Department employee. While others shunned assignment to China's remote far west, he was only too eager to set up a listening post there along the Sino-Soviet border.

(Courtesy of Pegge Hlavacek)

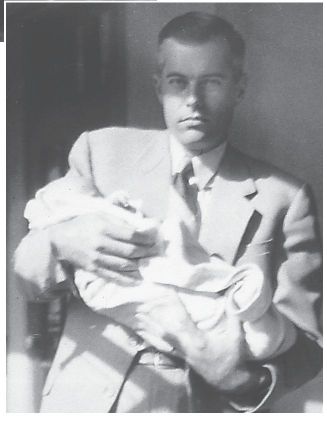

Douglas S. Mackiernan cradles his newborn son, Michael, in Shanghai in the fall of 1948. It would be the only picture of Mackiernan with his son. Weeks later Pegge and the twins were evacuated. Mackiernan, still posing as a State Department employee, was left behind to gather intelligence on the encroaching Communists.

(Courtesy of Pegge Hlavacek)

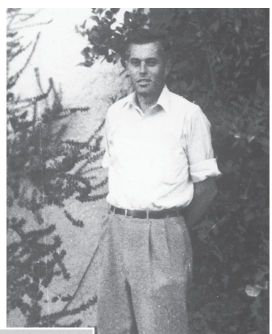

RIGHT: Douglas S. Mackiernan, shirtsleeves rolled up and standing outside the embassy in Tihwa, China. Months later he would be fleeing the Communist Chinese across an endless expanse of desert and mountains.

(Courtesy of Pegge Hlavacek)

BELOW: Douglas Mackiernan (standing in the middle) against a snowy landscape not unlike that across which he attempted to flee the Communists. He was proud of his new beard and swore he would not take it off until he and wife Pegge were together again.

(Courtesy of Pegge Hlavacek)

From the

San Francisco Examiner

, dated January 31, 1950. Mackiernan's widow, Pegge, with twins Mary and Michael, dismissing as “silly” the Chinese claim that her husband had been a spy. Fifty years later the CIA would still not utter his name or acknowledge that he worked for the Agency.

(Courtesy of Pegge Hlavacek and the

San Francisco Examiner)

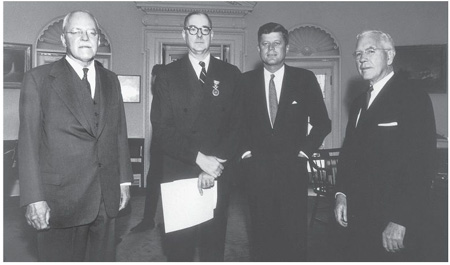

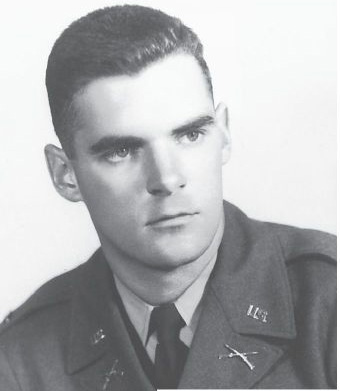

LEFT: William P. Boteler in uniform. He was never in the military, but his covert missions on behalf of the CIA were often done under military cover. In 1956, at the age of twenty-six, he was killed by a terrorist pipe bomb in Nicosia, Cyprus.

(Courtesy of Charles Boteler,

his brother)

BELOW: An honor guard stands at attention at a State Department memorial service in which Boteler's name was added to the department's list of honored casualties. Like so many other CIA fatalities, he died while under State Department cover.

(Courtesy of

Charles Boteler)

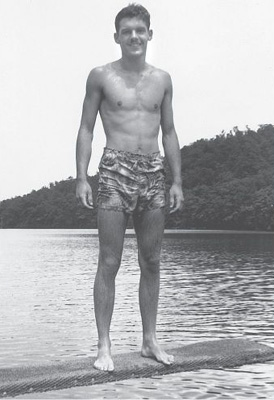

William P. Boteler as a summer camp counselor on a diving board.

(Courtesy of William Tammaro)

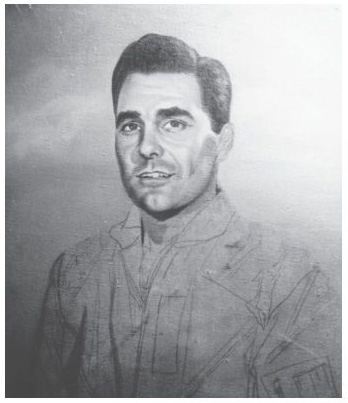

A portrait of Leo Baker, one of the Alabama pilots killed in the ill-fated Bay of Pigs operation against Castro in 1961. For thirty-nine years the CIA refused to publicly acknowledge that Baker and the other Americans who died were on Agency missions.

(Courtesy of Theresa Ann

Geiger, Baker's daughter)