The Book of Fate (53 page)

“Very first aide to any President. Right after Jefferson was elected in 1801, one of his first jobs as President was decreasing the number of officers in the army. The Revolutionary War was long over, the conflict with France was winding down, and they were trying to shrink the ranks.”

“So the political consequences . . .”

“Very good. Were staggering,” Mary Beth explained. “You have the political bug too, eh? Have you ever been to Monticello? I’d be happy to show you around.”

That was always the problem with the message boards. The odds were good, but the goods were odd. “I’m sorry, I’m just in a bit of a rush—”

“Okay, I get it—you’re married. My apologies. I’m just not good at reading these things—”

“Yes, so, aheh—you were saying about Jefferson . . . that the political consequences of firing officers . . .”

“Of course, of course. The politics were tricky to say the least, so to avoid putting his foot in it, Jefferson asked Lewis to secretly rank the loyalty of each army officer. That way, they’d know who to fire and who to keep on board.”

“So those symbols,” Kassal said, looking down at the

“. . . Lewis and Jefferson’s coded rating system to make sure none of the officers would ever find out what Jefferson’s opinion of them actually was: whether they were trustworthy, apathetic, or a political enemy. So when the War Department supplied Jefferson with the list of all the brigadier generals and lieutenants, Lewis took his secret symbols and put . . .”

“. . . a handwritten mark next to each name,” Kassal said, studying the exact same symbols two hundred years later on the crossword. “To everyone else, it looked like the random blots of a fountain pen . . .”

“. . . right again . . . but to Jefferson, it was a guide to which of his officers were honest Abes. In fact, if you ever do come h— We actually have the original list on display, plus the key that Jefferson used to decipher the codes. It’s beautiful to see up close—all the flourishes in the old script.”

“Certainly sounds

tempting

,” Kassal said, making the kind of face that usually goes with biting a lemon. “But . . . Mary Beth, is it?”

“Mary Beth,” she said proudly.

“If I could ask you one last favor, Mary Beth: Now that I have the signs—the four dots and the cross with the slash through it—can you just read me the cipher so I know what each of these stands for?”

Y

ou’re telling me you didn’t send him a note?” Rogo asked Boyle as he readjusted his shirt from where the guard had pulled it.

“Note? Why would I send him a note?” Boyle asked, sounding annoyed as his eyes flicked between Rogo and the guard.

“I said don’t move!” the guard shouted, his gun pointed at Boyle.

“You yell at me again, you’re gonna be picking that gun outta your teeth,” Boyle growled back. “Now I want my contact man, or at the very least, a supervisor, and I mean

now.

”

“What the hell’s going on?” Dreidel asked, his hands raised in the air, even though the gun wasn’t anywhere near him. “You said we were meeting at my hotel. Since when is Wes meeting at a graveyard?”

“Dreidel, this isn’t about you,” Rogo insisted. Turning to the guard, he added, “Listen, I know you don’t know me, but my friend’s life is in—”

“So is yours,” the guard said as he pointed his gun back at Rogo. Turning his attention to his walkie-talkie, he pushed a button and added, “Rags, we got a problem—I need you to find Loeb.”

“So wait . . . when Wes called . . . you

both

lied to me?” Dreidel asked, still putting the pieces together. “Now you have Wes not trusting me too?”

“Don’t you dare play victim,” Rogo warned. “Lisbeth spoke to your old girlfriend—the one with the crossword puzzle—”

Boyle turned at the words. “You found the puzzle?”

“Boyle, keep your mouth shut!” the guard warned.

“How’d she find Violet?” Dreidel asked, his face paste white as he slowly lowered his hands.

Rogo shook his head at Dreidel but knew enough to stay with the guard, who knew enough to stay with Boyle. Rogo shifted his weight anxiously, barely able to stand still. Every second they wasted here meant that Wes— He cut himself off.

Don’t think about it.

“When’d you find the puzzle?” Boyle added, still trying to get Rogo’s attention.

Rogo glanced his way, smelling the opening. Until he could get to Wes, he might as well get some answers. “Does that mean you’re gonna tell me what’s in it?” Rogo asked.

Boyle ignored the question like he didn’t even hear it.

“No—don’t do that,” Rogo warned. “Don’t just— If you can help Wes—if you know what’s in the puzzle—”

“I don’t know

anything.

”

“That’s not true. You went to Malaysia for a reason.”

“Loeb, you there?” the guard said into his radio.

“C’mon, Boyle—I heard Wes talk about you. We know you tried to do the right thing.”

Boyle watched the guard, who shook his head.

“Please,” Rogo pleaded. “Wes is out there thinking he’s meeting you.”

Boyle still didn’t react.

“Someone lured him out there,” Rogo added. “If you know something and you keep it to yourself, you’re just letting him take your place.”

Still nothing.

“Forget it,” Dreidel said. “He’s not—”

“Where’d he find it?” Boyle blurted.

“Find what?” Rogo asked.

“The note. You said Wes found a note. For the graveyard.”

“Boyle . . .” the guard warned.

“On his car,” Rogo sputtered. “Outside Manning’s house.”

“Since when?” Dreidel asked. “You never said that. They never said that,” he added to Boyle.

Boyle shook his head. “And Wes just assumed it was—? I thought you said you unlocked the crossword.”

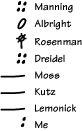

“We unlocked the names—all the initials,” Rogo said. “Manning, Albright, Rosenman, Dreidel . . .”

“These . . . with Jefferson’s old cryptogram,” Boyle said as he pulled a worn, folded-up sheet from his pocket. Furiously unfolding it, he revealed the crossword and its hidden code, plus his own handwritten notes drawn in.

“That’s the one,” Rogo said. “But aside from telling us that the President trusted Dreidel, we couldn’t—”

“Whoa, whoa, time out,” Boyle interrupted. “What’re you talking about?”

“Boyle, you know the rules on clearance!” the guard shouted.

“Will you stop worrying about clearance?” Boyle barked back. “Tell Loeb he can blame it on me.” Turning back to Rogo, he added, “And what made you think Dreidel was trustworthy?”

“You’re saying I’m not?” Dreidel challenged.

“The four dots,” Rogo explained as he pointed at the four dots. “Since the President and Dreidel are both ranked with four dots, we figured that was the inner circle of who he trusted.”

Boyle went quiet again.

“That’s

not

the inner circle?” Rogo asked.

“

This

is the inner circle,” Boyle said, pointing to the

0

next to Manning’s chief of staff, the man he used to do the puzzles with.

“So what’re the four dots?” Rogo asked, still lost.

“Boyle, that’s enough,” the guard warned.

“This has nothing to do with clearance!” Boyle challenged.

“Those four dots are good,” Dreidel insisted. “Manning trusted me with everything!”

“Just tell me what the four dots were,” Rogo demanded in a low voice.

Boyle glared at Dreidel, then back to Rogo. “The four dots were Jefferson’s shorthand for soldiers without any political creed—the opportunists who would give up anything for their own advancement. For us, it was meant to describe who Manning and Albright thought were leaking to the press. But when The Three found a copy and deciphered it, that’s how they knew who to pick for their fourth.”

“I’m not The Fourth!” Dreidel insisted.

“I never said you were,” Boyle agreed.

Rogo glanced down at Manning’s old crossword, studying the two names with the four dots.

None of it made sense. Wes swore that the handwriting—that all the rankings—were Manning’s. But if that’s true . . . “Why would the President give himself such a low ranking?”

“That’s the point. He wouldn’t,” Boyle said.

“But on the crossword . . . you said the four dots—”

Boyle raked his bottom teeth across his top lip. “Rogo, forget your biases. The Three wanted someone close to every major decision, and most important, someone who could

affect

those decisions—that’s why they first picked me instead of Dreidel.”

“Boyle, that’s

enough

!

I’m serious!

” the guard shouted. But Boyle didn’t care. After eight years, there was nothing more they could take from him.

“You see it now, don’t you?” Boyle asked as Rogo stared down at the page. “You’ve got the right name. Even the right reasoning—never underestimate what they’d do for four more years. But you got the wrong Manning.”

Confused, Rogo shook his head, still locked on the puzzle. “What other Manning is th—?”

A burst of bitter cold seized Rogo’s body, as if he’d been encased in ice.

Oh, shit.

I

know her shadow anywhere. I know it better than my own. I’ve watched it nearly every day for almost a decade. That’s my job: trailing three feet behind her, close enough to be there the moment she realizes she needs something, but far enough that I’m never in the photo. Back during White House days, even when she was swarmed by entourages of dignitaries and foreign press and our press and staff and crowds and Secret Service, I could still stand at the back of the horde, peer through the sea of legs, and find her silhouette at the center—and not just because she was the only one in high heels.

It’s no different tonight. Indeed, as I squat down in the shadowy graveyard and hide behind one of the meatball shrubs, as I clamp my eyes into paper-thin slits and try to squint through the braided crisscrossing branches and the nearly fifty yards of headstone-lined darkness, I stare down the crooked stone path and instantly recognize the thick calves, sharp shoulders, and pointed silhouette of Dr. Lenore Manning.

An aching pain swells like a balloon inside my rib cage. No . . . she—she’d never— I shake my head, and my ribs feel like they’re about to splinter. How can—? Why would she do that?

At the end of the path, stopping at the tree, she tips her umbrella slightly, and in the light from the distant flagpole, I see anger and annoyance—and even fear—in her face. I can still picture her leaving the White House—the President squeezing her fingertips as they walked to Marine One. She said it herself: When it came to staying in power, they would’ve done almost anything.

She barks something at the man next to her, but I’m too far away to hear it. She’s not happy to be here. Whatever she did, she’s clearly regretting it. I pull back, blinking violently. But Boyle . . . If the First Lady’s here, and the man next to her, with the bandages on his right hand (is that a gun?), if that’s The Roman . . . A rush of blood throbs up from my chest, all the way to my face. I hold my cheek, which burns against my hand, just like when I was shot.