The Body Economic (5 page)

Authors: David Stuckler Sanjay Basu

F

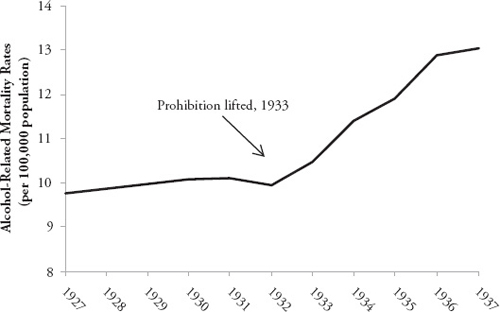

IGURE 1.4

Death Rates from Alcohol, US, 1927 to 1937

31

The election pitted the incumbent president, Republican Herbert Hoover against Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt. To the millions of Americans plunged into poverty, Hoover's campaign advice that people should “pull themselves up by their bootstraps” seemed singularly out of touch. Hoover believed that if anyone should provide relief to the unemployed and homeless, it should be private charities and local governments, not the federal government.

33

While Roosevelt was initially not far from Hoover in this opinion, he experienced enormous political pressures from the nation's left. Much of this pressure came from a groundswell of labor unrest. Between 1929 and 1931, the wages of auto workers in Michigan had dropped by 54 percent. By 1932, more than 200,000 people in the auto industry had lost jobs, a third of whom had been laid off from Ford's factories. On March 7, 1932, in Dearborn, Michigan, 4,000 unemployed workers led a hunger march. They had

come together to protest their shared fate: hunger, poverty, and unemployment. The workers carried banners bearing slogans such as “Give Us Work, We Want Bread Not Crumbs” and “Tax the Rich and Feed the Poor.” Their march was peaceful until Ford security guards and police tried to stop it. They fired tear gas into the crowd. Marchers responded by throwing stones. And then Ford security guards shot into the crowd, killing fourteen and wounding fifty. What had started as the Ford Hunger March had ended as the Ford Massacre.

34

The Ford March was followed by similar battles across the country. Workers began to join together, in some cases forging new collective organizations such as the United Auto Workers Union in 1935. The super-rich came to be viewed as drivers of the crisis, given their involvement in the risky land deals and financial transactions that had precipitated Black Tuesday. This popular criticism of the rich led to a swelling of support for the US Socialist Party, largely composed of farmers who had lost their land and factory workers who had been laid off.

35

The political left became more powerful than ever before in US history. Roosevelt grew concerned that union support for Socialist presidential candidate Norman Thomas would split the left-wing vote and give Hoover a second term. And so Roosevelt promised to implement social protection programs to help farmers and factory workers recover from the Depression. His promise tipped the balance in his favor, and he won the election. In his inaugural address, Roosevelt said: “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a New Deal for the American people.”

36

The New Deal would eventually include such ground-breaking programs as the Federal Emergency Relief Act and Works Progress Administration, which gave 8.5 million jobless Americans work by creating new construction projects; the Home Owner's Loan Corporation, which prevented at least a million foreclosures; the Food Stamp Program, which gave vouchers for basic foods to those who could not afford them; the Public Works Administration, which built hospitals and provided immunizations for Americans who could not afford them; and the Social Security Act to combat poverty among senior citizens.

37

The New Deal had a momentous effect on the public's health. Although it was not designed with public health in mind, its support meant the difference between losing healthcare and keeping it; between going hungry and

having enough food at the table; between homelessness and having a roof overhead. In providing indirect support to maintain people's well-being, the New Deal was in effect the biggest public health program ever to have been implemented in the United States.

To study the effects of the New Deal on public health, we scrutinized the differences between death rates that emerged after the New Deal was implemented. But we could not simply look across the entire country, because health was being affected by the ongoing recession and epidemiological transition. We needed to measure variation in each state's exposure to the New Deal in order to statistically isolate the effect of Roosevelt's programs.

Here, we looked to the politics of the New Deal for clues. There were major differences among states in the extent to which they implemented FDR's programs. In general, we found that states with left-leaning governors, who were politically aligned with Roosevelt, tended to invest more in New Deal programs than their Republican counterparts did. The New Dealâsupporting politicians funded more housing programs, invested more in construction projects to generate jobs, and supported food stamps and welfare aid. By contrast, conservative governors sought to minimize New Deal programs, even cutting many of their state budgets to reduce deficits.

38

The stark contrasts between states' responses to the Great Depression created variation in the degree to which the New Deal was implemented across the country. In social science research, we call such an historical episode a “natural experiment,” because it gives us an opportunity to identify the effects of a policy. While it would be impossible to randomize some US states to participate in the New Deal and others not to participate, as in a medical experiment, the choices of these politicians created a real-world laboratory where we could see whether those states that had more New Deal spending gained better health as a result. Statistically, we accounted for a number of other factors that could affect these results, like different demographics, different pre-existing health conditions, education levels, income, and a variety of other control variables that we included in our analyses.

Louisiana became a prime showcase for the New Deal. Governor Huey Long was one of its most vocal supporters, but he felt it didn't go far enough. So he launched the Share Our Wealth movement in 1934 and called for higher taxes on the wealthy and corporations in order to fund public works, schools, and pensions. Under Long's leadership, Louisiana invested about

$50 per person per year in social protection spending, whereas the governors of Georgia and Kansas devoted about half as much to such spending. Under Long, Louisiana created new programs for nutrition, sanitation, and public health education, doubled funding for the public hospital system, and provided free immunizations to nearly everyone who couldn't afford them. Long started night schools that taught 100,000 adults to read, founded the Louisiana State University School of Medicine, doubled funding for the public charity hospital system, and extended free immunizations to 70 percent of the populationâall during the worst economic crisis in history.

39

New Deal and Share Our Wealth programs made a difference. It was so big a difference that a major gap developed between states that supported the New Deal and those that did not, even among states that started out in similar public health and economic situations. People in Louisiana and other states implementing New Deal measures benefited from significantly greater declines in infectious diseases, child mortality, and suicides, particularly when compared with people in states like Georgia and Kansas that didn't implement these measures.

40

Overall, New Deal programs not only helped avert further economic disaster but also were statistically correlated to large and lasting public health improvements. The Great Depression created conditions that public health experts expected would spread infectious diseases, but infections fell steadilyâwith the biggest declines in the cities and states where New Deal housing programs helped prevent excessive crowding. Across the United States, each $100 per capita of New Deal spending was, on average, linked to declines in pneumonia by about eighteen deaths per 100,000 peopleâa remarkable improvement at a time when effective drugs to combat the disease were not widely available.

The New Deal also helped improve children's survival, as construction and rebuilding programs prevented shantytowns from becoming slums where stagnant water and overcrowding often led to diarrhea and childhood respiratory tract infections. Across the United States, each $100 per capita of New Deal spending was on average linked to reductions in infant deaths by eighteen per 1,000 live births.

And the New Deal was associated with reduced suicide rates. As shown in

Figure 1.3

, the first year of the New Deal (1933) marked the turning point in the rise in suicides. Using extensive statistical models controlling for alternative explanations, we found that each additional $100 per person of New

Deal spending was associated with a significant decline in suicides by four per every 100,000 people.

At the time, the American medical community was impressed by the results. Dr. William Welch, president of the American Medical Association, maintained that government investment in public health programs was not only a matter of saving lives and improving people's quality of life, but also making sound investments that would benefit the economy. “Any undue retrenchment in health,” said Welch, “is bound to be paid for in dollars and cents as well as in the impairment of the people's health generally. We can demonstrate convincingly that returns in economic and social welfare from expenditures for public health service are far in excess of their costs.”

41

Welch was rightâthe New Deal programs were affordable even during Depression times. By today's standards, they still offer good value for the money. The social protection programs were as cost-effective, with similar costs per life saved, as common medications.

42

Overall, the size of these New Deal relief programs constituted less than 20 percent of the gross domestic product. And they not only reduced deaths but also sped up economic recovery. The New Deal brought an immediate 9 percent rise in average American income, increasing people's spending and helping to create new jobs. Rather than creating a vicious negative spiral of increasing debt and deficits, as critics of the New Deal had predicted, the stimulus helped the US economy grow out of debt.

43

At the time, politicians and the public didn't have access to data that we have at our disposal. In hindsight, it is possible to see clearly the lasting benefits of the New Deal, both to the economy and to public health.

44

Undoubtedly, many of the health effects of the Great Recession will differ from those of the Great Depression. Prohibition is no longer in place, and our investigation into alcohol-related deaths during the Great Recession has found that more Britons and Americans are choosing to abstain from alcohol to save money. But we also found that a small, at-risk group has had the opposite reaction to our current recession: when faced with unemployment, they began drinking heavily. In the UK, where most people are still employed and drinking less overall, those people who lost work during the recession were much more likely to binge drink. Similarly, most Americans are drinking less during the Great Recession, but there is a hidden group of about 770,000 who now drink more dangerously, often landing in emergency rooms. These Americans

have experienced a spike in death rates from acute intoxication and alcohol-induced liver failure.

45

Political leaders on both sides of the Atlantic now face choices similar to those confronted by Hoover and Roosevelt. Another large, natural experiment is being unleashed on the people of both countries. Under Prime Minister Cameron's austerity measures in the UK, we see more and more sad stories like that of Brian and Kieran McArdle. The UK economy has yet to recover, as its debt continues to rise. Meanwhile in the US, President Obama is constantly battling with Republican deficit hawks, but has insisted on keeping and strengthening the safety net. And while not quite going so far as a New Deal, the US stimulus has helped lead the country to a slow but real recovery so far.

What the Great Depression shows us is that even the worst economic catastrophe need not cause people's health to suffer, if politicians take the right steps to protect people's health. The Great Recession involves a fundamental political choice: whether to apply the lessons of the Great Depression and the New Deal, or to chart an altogether different path that could have dire consequences.

THE POST-COMMUNIST MORTALITY CRISIS

Ten million Russian men disappeared in the early 1990s.

The Russian Republic of the Soviet Union had more than 147 million residents. Its population had been growing at the same rate as the United Kingdom in 1990 and 1991, at about 0.3 percent per year. But in 1992, Russia's population began to vanish. The United Nations had been tracking data on the populations of all nations, and when they noticed this drop, they contacted a team of researchers in Russia.

1