The Black History of the White House (49 page)

Read The Black History of the White House Online

Authors: Clarence Lusane

African Americans were involved in mainstream city politics as well. Chicago produced the first African American to return to the U.S. Congress in the twentieth century, Representative Oscar De Priest, elected in 1928. The number of black congressmembers from Chicago would grow and, strikingly, include three of the four blacksâCarol Moseley Braun (1993â1999), Barack Obama (2005â2008), and Roland Burris (2009â2011)âelected or selected to the U.S. Senate in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

9

Beyond the excitement generated by Chicago-based activist Jesse Jackson's presidential runs in 1984 and 1988, progressives around the nation gave enthusiastic support to the historic mayoral campaign that elected Harold Washington (1984â1987). Nearly all these political activities would occur within the orbit of the Democratic Party, which has dominated city politics for decades. The Democratic Party in Chicago, as in other Northern cities, recruited blacks not only to be candidates but also to perform the nitty-gritty, street-level party work, many serving as precinct captains. Their role was essential to the maintenance of Democrat authority, as they were directly responsible for turning out the vote in exchange for favors, funds, and other benefits.

One of those precinct captains was Fraser Robinson III. His grandfather, Jim Robinson, had been born enslaved in Georgetown, South Carolina, around 1850, the same year that Melvinia was sold and sent to Georgia. Jim and his wife Louisa had at least two children, Gabriel, who was born around 1877, and Fraser, born in 1884. Fraser married Rose Ella Cohen and their son, Fraser Jr., would be among the millions of African Americans who left the South between World War I and World War II to seek a better life in Northern cities. In Chicago, Fraser Jr. met and married Illinois-born LaVaughn Delores Johnson, who may have been a descendant of blacks who had been free since before the Civil War. Life would be hard for the couple, and there was a period when Fraser abandoned the family, later to return. In 1935, the couple gave birth to Fraser III. LaVaughn and Fraser Jr. would return to Georgetown, South Carolina, after their retirement.

10

Given the difficult personal times and the Depression era, Chicago-born Fraser III grew up poor, and the family spent some time on welfare during his childhood. As a result he began working on a milk truck at the age of eleven. As an adult, Fraser worked at the Chicago Water Department tending boilers as a pump operator despite being physically challenged by multiple sclerosis, which he had developed when he was young. He walked with crutches but still managed to be an outstanding employee who rarely missed a day of work.

At one point, Marian Lois Shields and Fraser Robinson III met, fell in love, and married. They would occupy a one-bedroom apartment in a brick bungalow in an essentially all-black neighborhood. Marian worked as a secretary but left the job to start a family. She and Fraser had two children, Craig (April 21, 1962) and Michelle (January 17, 1964). Fraser would play a key role in the achievements of his children, but he died

in 1991 before he could witness the heights of their success. Marian and Fraser had always emphasized the importance of education, and both children were extremely bright. They excelled academically, both learning to read at age four. According to Craig, in 1979, when he was indecisive about whether he should go to Princeton University or the less prestigious but more affordable University of Washington or Purdue University, he turned to his father for counsel. His father stated, “If you pick your school based on how much you have to pay, I'll be very disappointed.”

11

Craig went to Princeton. He later became a successful businessman and then a winning basketball coach at Brown University and Oregon State University.

12

His younger sister, Michelle, followed him to Princeton two years later. Thus began the path that would eventually lead to her meeting a young black lawyer named Barack Obama.

Michelle became very conscious about issues of discrimination and prejudice while studying at Princeton, a time she describes as difficult for her and the other few black students on campus. Her senior thesis was titled, “Princeton-Educated Blacks and the Black Community,” where she wrote that her experiences at the school made her more aware of her “blackness” than ever before and that, “I sometimes feel like a visitor on campus, as if I really don't belong.”

13

Despite these feelings, she dug in and graduated cum laude with a Bachelor of Arts in sociology. Three years later she earned a Juris Doctor degree from Harvard Law School, graduating only months before Obama started working toward his law degree at the same school. Michelle went to work for the Sidley Austin law firm in Chicago in 1988, and the following year she met Obama, who was a summer intern assigned to the firm. On October 18, 1992, the couple married at Trinity United Church; Michelle's

childhood friend Santita Jackson, Jesse Jackson's daughter, sang at the ceremony.

Michelle's life was changing dramatically during this time. Her father died the year before her marriage, and she decided to leave the corporate world for more public serviceâoriented work. She took a job as an assistant to Mayor Richard Daley Jr., became Chicago's Assistant Commissioner of Planning and Development, and then developed community outreach programs for the University of Chicago, University of Chicago Hospitals, and University of Chicago Medical Center. This work would place her in a position to meet and work with people, organizations, and institutions all across the city. She clearly had the capacity, skill, talent, and connections to be a successful politician, if she so desired. That role, however, would be played by her husband. It is likely that Michelle's father Fraser, the former precinct captain, would have relished his son-in-law's interest, involvement, and success in Chicago politics.

This was the historical environment and contextâa trajectory through the slave plantations of South Carolina, tenant farms of Georgia, and black working-class neighborhoods of Chicagoâthat produced Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama, a gifted, sophisticated, intelligent, committed, forthright, and physically stunning woman who has brought a superb dignity to the White House. She has been steadfast in the face of racist attacks on her, her husband, and even her family, as well as sexist attacks on herself, always responding, when response was called for, in an appropriate and measured manner.

During Obama's run for the White House, most critics viewed her articulate, poised, and dignified presence as a valuable asset to the campaign. There was an effort by some conservativesâincluding Cindy McCain, John McCain's wifeâto portray her as anti-American after she stated at a February 18, 2008, rally in Madison, Wisconsin, “For the first time in my adult lifetime, I'm really proud of my country, and not just because Barack has done well, but because I think people are hungry for change.” The charge did not stick. Most people of color rejected the accusation that Michelle was “anti-American.” For many African Americans, Latinos, Asians, Native Americans, and others, the country's long violent history of racist exclusion has never been a source of pride. For communities of color, who have been marginalized for generations, endured segregation, and survived the era of lynching, it has been the nation's progressive stepsâsuch as ending legal discrimination or long-standing racial, gender, or class barriersâthat have inspired a sense of pride, patriotism, and national community.

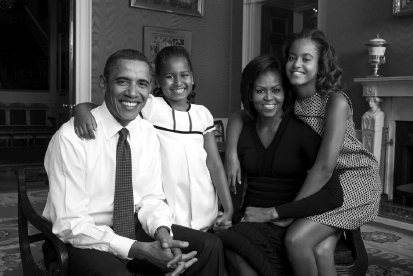

President Barack Obama, First Lady Michelle Obama, and their daughters, Malia and Sasha, in the Green Room of the White House, September 1, 2009.

On January 20, 2009, the Obama familyâMichelle, Barack, their daughters Malia Ann and Natasha (Sasha), and

Michelle's mother Marianâofficially moved into the White House. The long saga of African Americans and the White House that began with enslavement, followed by a century of legal segregation and racist terrorism, and continuing with present-day racial disparities, had finally culminated in changing the color of the residents of the most famous address in the nation, 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C. For the first time in U.S. history, the First Family in the White House was African American.

Becoming the First Black President of the United States of America

I've seen levels of compliance with the civil rights bill and changes that have been most surprising. So, on the basis of this, I think we may be able to get a Negro president in less than 40 years. I would think that this could come in 25 years or less.

14

âMartin Luther King Jr. in an interview with the BBC, on his way to Oslo, Norway, to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964.

When Martin Luther King Jr. made his prediction about when a black presidency might be possible, he was responding to a question from a BBC interviewer. King began his response by stating, “Well let me say first that I think it is necessary to make it clear there are Negroes who are presently qualified to be president of the United States. There are many who are qualified in terms of integrity, in terms of vision, in terms of leadership ability.”

15

King's assertion about black leaders' integrity, vision, and leadership capabilities was one that most whitesâeven the most liberalâwould have rejected at the time. King was also, of course, astute enough to identify the barriers to such an event. He went on to add, “But we do know there are certain problems

and prejudices and mores in our society that make it difficult now.”

16

Clearly King was being diplomatic and calculated in his words: at that point he had been the target of assassination attempts, and the body count of murdered civil rights organizers was growing. In many ways, a second Civil War was under way, as White Citizens Councils, the Ku Klux Klan, law enforcement, elected officials, and others with a vested interest in the system of segregation were armed and ready for a fight to the death.

All that said, King still painted a hopeful picture of the years ahead, stating, “I'm very optimistic about the future. Frankly, I have seen certain changes in the United States over the last two years that have surprised me.”

17

King is speaking in late 1964, a few months after the Civil Rights Act had been signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson, before the battle over the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the horrific attacks by police officers, state troopers, and local thugs on civil rights activists, notably on that last great march of the era, over the Pettus Bridge near Selma, Alabama.

18

The journalist's question had been inspired by an earlier quote from then attorney general Robert Kennedy, who stated in May 1961, “There's no question that in the next thirty or forty years, a Negro can also achieve the same position that my brother has as President of the United States, certainly within that period of time.”

19

Given the toxic racial divisions at the time, including legal segregation, Kennedy was speaking very optimistically, perhaps assuming a much greater capacity and willingness on the part of his newly elected brother John to move a civil rights agenda, tone down the vitriolic rage spewing out of the South, and deal with a Congress dominated by Southern Dixiecrats. Both King and Kennedy would come up slightly short in their prediction of when the first black president of the United States would be elected.

Race, Racism, and Obama's White House

I chose to run for the presidency at this moment in history because I believe deeply that we cannot solve the challenges of our time unless we solve them togetherâunless we perfect our union by understanding that we may have different stories, but we hold common hopes; that we may not look the same and we may not have come from the same place, but we all want to move in the same directionâtowards a better future for our children and our grandchildren.

âBarack Obama

How long does it take to become president of the United States? By one measure, it took Barack Obama 1,638 days, from July 27, 2004, when he gave the celebrated speech at the Democratic National Convention that introduced him and his message of unity to the nation, to January 20, 2009, when he took the oath of office. His meteoric political ascent to command the highest office in the land was driven, of course, by all that came before him, a long preparatory period for the nation's racial politics and much more. Paradoxically, Obama won because of race and in spite of it.

The images of the Obama family entering the White House transfixed the world. Aware of the long history of white enslavement and racial segregation of blacks, millions across the globe sensed that they were witnessing a barrier of immense importance being broken, and the image of the White House and of the United States itself would be forever transformed. The worldwide celebration of Obama's electoral triumph and subsequent inauguration bespoke an identification on the part of billions and their hope that social marginalization, discrimination, and oppression could be overcome.