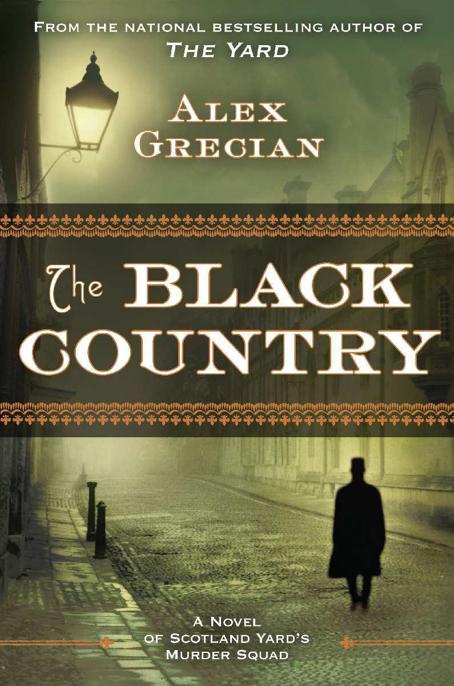

The Black Country

ALSO BY ALEX GRECIAN

The Yard

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Publishers Since 1838

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA

•

Canada

•

UK

•

Ireland

•

Australia

•

New Zealand

•

India

•

South Africa

•

China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com

Copyright © 2013 by Alex Grecian

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Grecian, Alex.

The black country / Alex Grecian.

p. cm

ISBN 978-1-101-62106-6

1. Murder—investigation—England—Fiction. 2. Detectives—England—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6107.R426B53 2013 2013003820

823'.92—dc23

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

For Graham,

who is not allowed to read this until he’s much older

Rawhead and Bloody Bones

Steals naughty children from their homes,

Takes them to his dirty den,

And they are never seen again.

—Black Country children’s rhyme

I

t was an unusual egg. Not at all like other eggs Hilde had seen. It was slightly larger than a robin’s egg, white with a thin spiderweb of red, visible under a paper-thin layer of snow. A bit of dirty pink twine curled out from under the egg, and Hilde reached out, nudged it with her fingernail. The egg turned, rolling over in its nest of straw and feathers and bits of old string. Hilde could see now that the worm-thread was embedded in mud on one side of the egg and on the other side of the egg was a large colored dot, slate blue, darker than a robin’s egg ought to be.

She adjusted her position in the tree, resting her behind against a big branch to free her hands. She looked down at the ground, but there was nobody to see what she was doing or to tell her no. Carefully she reached into the nest and plucked out the unusual egg. It was slippery, not as firm as the eggs she had handled in the past, and its surface gave a little under the pressure of her fingertips.

She held it up to the pale sun, turning it this way and that. It glistened, a dappled branch pattern playing over its surface. She brought it closer to her face. The blue dot in the center ringed a smaller black spot and reminded her of something, but it was out of context and it took her a long moment to place it.

And then she did and it was an eye, and the eye was looking at her.

Hilde reeled back and dropped the eyeball. It tumbled down through the branches below, bouncing once, then twice, off the trunk, and disappeared into a pile of soft snow-covered underbrush. Her foot came loose from its perch on the branch and she felt herself slip. Her weight fetched up against a smaller branch to the side, but it didn’t hold her. She felt the adrenaline rush too late as she grabbed for the nest and it came loose in her hand. Her dress snagged and tore, and all of her sixty-three pounds caromed off the branch and slammed back into the tree trunk.

Still holding the useless bird’s nest, Hilde fell to the ground, screaming all the way.

T

HE

VILLAGE

OF

B

LACKHAMPTON

,

T

HE

M

IDLANDS

, M

ARCH

1890

I

nspector Walter Day stepped off the train and directly into a dirty grey snowbank that covered his ankles. He was a solid block of a man with dark hair swept straight back from his face, and he smiled at the fat flakes that eddied in the train’s exhaust. The ride from London had been longer than expected, and he was tired and thirsty and nervous, but he took a moment to breathe in the fresh air. He set his suitcase down and raised his face to the sky, stuck out his tongue, and tasted the cold wet pinpricks of melting snow.

“Ow bist?”

Day turned to see a stout man in a blue uniform striding toward him. The man’s cheeks were red and raw, and ice glinted in his thick handlebar mustache.

“I’m sorry?” Day said.

“You the inspector, then?”

“I am. And you’d be Constable Grimes?”

“I am,” Grimes said. He put his hand out before he had reached Day and hurried to make up the distance, his arm held out like a lance between them. “Welcome to Blackhampton, sir. Quite excited to be workin’ with the Yard. Been a dream of mine.”

Day was flattered. This distant sheltered village still respected the detectives of Scotland Yard, saw them as a force for good. London was a different matter. Jack the Ripper had ravaged London and left his nasty mark on a city that had since become cynical and scornful of its police. Scotland Yard was in the process of rebuilding, but it was a daunting task. Day had only been with the Yard for six months, much of that on the new Murder Squad, twelve men tasked with hunting murderers like Saucy Jack. The commissioner, Sir Edward Bradford, had told Day he could spare him for only two days, so two days it was. He hoped it would be enough.

“We’ll try not to let you down.” Day took a few steps in Grimes’s direction and shook the constable’s hand.

“Let’s get your luggage,” Grimes said, “and I’ve got the carriage here to take you straight round to the inn. Cozy place, I think you’ll find. They do it up good there.”

“Thank you. I’ve just got the one bag here. But we’re waiting for my sergeant.”

“Sergeant? Was told to expect a detective and a doctor.”

“The doctor will be along tomorrow. He had pressing business in London.”

“So we’ve got an extra man, do we?”

“It seems you do.”

“Well, we’ll find room for him.”

Day wondered whether there was a territorial issue. One detective might be of assistance to the constable. But two men from the Yard might seem like a threat. The local law was already outnumbered.

“I’m sure we’ll depend on you completely,” Day said.

“No worries there.”

“Dash it all!” Sergeant Nevil Hammersmith’s voice preceded him, muffled by the noise of the train’s engine. “It’s cold.” Hammersmith hove into view carrying a small canvas bag. He stepped down from the train and shook his head at Day. The sergeant was tall, and rapier thin, and his unkempt hair hung over his eyes. His coat was unbuttoned, and a large wet spot decorated the front of his shirt.

“I’m sure that doesn’t help with the cold,” Day said. “The wet, I mean. Makes it colder yet when the breeze hits you.”

Hammersmith looked down at himself. “I don’t think it’s helped the shirt, either.”

“Did we spill?” Constable Grimes said.

“Train lurched,” Hammersmith said. “When it entered the station.”

“Perhaps the innkeeper will be able to get that tea stain out,” Day said.

“What say we get you out of this wind and somewhere warm?” Grimes said. “Got any other luggage, Sergeant?”

“Just this.”

“I admire a gentleman who travels light.”

Before Day could pick up his suitcase, Grimes grabbed it and led the way past the depot through shifting snowdrifts. Hammersmith was left to carry his own bag. He raised an eyebrow at Day, who shrugged. The constable’s notion of their pecking order was clear enough. Day put a hand on Hammersmith’s arm and let Grimes walk ahead so that they wouldn’t be heard.

“What is it?” Day said.

“What do you mean?”

“Something’s troubling you. I can tell.”

“This snow is half ash from the furnaces,” Hammersmith said. “It’s grey.”

“Only half grey,” Day said. “Still white beneath the surface. There’s good to be found in everything.”

“That’s fine talk for a detective of the Murder Squad.”

Day smiled and looked past the station to the snowy field and, far beyond it, the pit mounds, the huge tanks of steaming wastewater, the tiny engine houses, and the iced-over stream that wound past them all. Here and there the snow made way for long furrows of mud and hopeful clusters of green spring grass. He pulled his coat tighter around his body. He waited, and Hammersmith finally nodded and pointed past the evidence of a thriving coal village. A dark line of trees stretched across the horizon.

“A forest,” Hammersmith said. “Coal mines. Furnaces. The water. We only have two days to find three missing people in all this. It’s impossible. There are too many places to look.”

“We’ll find them. If they’re dead, we’ll find bodies. If they’re alive . . .”

“If they’re alive, they’ll be moving about and we might never find them.”

“We’re not the Hiding Squad, after all,” Day said. “We weren’t sent for because anyone thinks they’re alive. And if murder’s been done, two days ought to be enough time to prove it.”

“If they’re not found when we have to go back, you could always leave me here.”

“I’m not going to leave you anywhere. The squad hasn’t enough men as it is and we have cases piling up at the Yard. I’m frankly surprised Sir Edward sent us here at all.”

Constable Grimes waved to them from the running board of a carriage parked at the station house. “You men comin’?”

Day and Hammersmith trotted across the springy boards of the platform floor and down the steps to the waiting carriage. The driver stuck his mouth in the crook of his elbow and emitted a series of short barking coughs. He shook his head as if dazed by the effort, then smiled and waved at them.

“That’s Freddy,” Grimes said. “He drives the carriage, but you’ll see him tendin’ to most everythin’ else needs doin’ round here.”

“You fellas need an errand, you look ol’ Freddy up and I’ll run it,” Freddy said. He appeared to be barely out of his teens, red-haired and freckled, with a gap between his two front teeth. Even sitting, his right leg was noticeably shorter than his left and rested on a block of wood that was affixed to the floor in front of the driver’s seat, but the boy’s grin seemed genuine and infectious. Day smiled back and nodded.

Something drew Freddy’s eye, and he pointed to the sky behind the inspector. “Look there,” he said. “Magpie.”

Day turned to see a small bird with a black head and a white belly flutter up past the far side of the depot. It banked and wheeled back on its own flight path, then straightened out and flew on.

“Bad sign, that,” Grimes said.

“Wait,” Freddy said. “Look.”

Three more magpies erupted in a flurry of beating wings and joined the first. They glided overhead and away toward the distant woods.

“Four,” Grimes said.

“Is that significant?” Day said.

“Maybe. Maybe not. One is for sorrow, of course. So it’s good to see the other three.”

“One bird brings ill fortune?”

“Ah, you know. One for sorrow, two for mirth, three for a wedding, four for a birth. Old rhyme. Not sure I give it much credence, but there’s some round here what does.”

“Four for a birth, eh?” Hammersmith said. He smiled at Day.

“None round here’s expecting, far as I know,” Grimes said.

“My own wife is due to give birth soon enough,” Day said. “Back in London.”

“Congratulations to you,” Grimes said. “Could be that’s what the birds was tryin’ to tell us.”

The three police clambered into the carriage. They heard a “haw” from Freddy, and the wagon rolled smoothly forward.