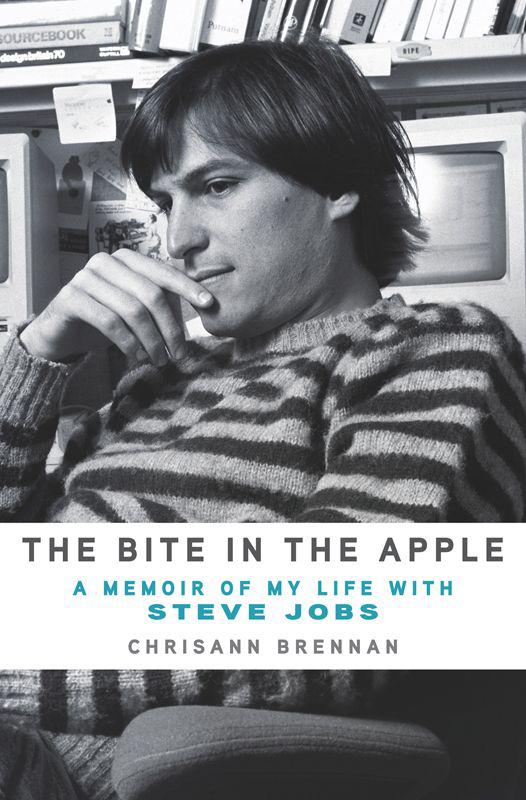

The Bite in the Apple: A Memoir of My Life with Steve Jobs

Read The Bite in the Apple: A Memoir of My Life with Steve Jobs Online

Authors: Chrisann Brennan

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

To Lisa, who is the whale rider

CONTENTS

3.

Experimental Flowering in Full Tilt Boogie

10.

The Practical and the Poetic

18.

The Reality Distortion Field

NOTE TO THE READER

There are three things I never thought I would do in this life: study history (history gives me migraines); play the drums (I’m just not very good at it); and write a book. And here I am writing a note to the reader … of my book.

Over the years, a number of people have encouraged me to write my story. And many more have warned me off it, even going so far as to say that I didn’t have the right. This

right

that they were talking about was the right to tell the story of my history with Steve Jobs. I met Steve when I was just seventeen. I became his first love and the mother of his first child and, as such, I have a unique perspective to share on this man who has fascinated the world. I’ve always been reluctant to share my story. For one thing, most of my time and attention has been devoted to my daughter, Lisa, and to my life and work as an artist. For another, my relationship with Steve was nuanced and difficult; I never wanted to revisit that history, much less go public about it.

Never say never.

In July of 2006, I became sick. Doctors were unable to diagnose the problem. I wasn’t able to work—the fumes from my painting exacerbated my illness—and within five months I was virtually homeless. My illness slowed me down and left me bored and scared. So I found myself reaching for something meaningful on which to focus. I put my things into storage, packed up my car, and traveled around the Bay Area—from Marin to Santa Cruz counties—staying with friends while trying to heal. I drove up to visit my father in Sacramento and it was then, while I was alone in my car, that I had the first spark of an idea to write this book. The words came to me:

It’s time.

My circumstances were dire and I can say now that nothing short of these dire circumstances would have led me to do the painstaking work of looking back into that history with Steve, much less write about it. But as I had nothing left to lose, I began.

Writing a memoir is a lot like spelunking. Headlamp on, I felt as if I were dropping down into deeper and darker caverns, negotiating vast and tight spaces to discover the great and terrible beauty that had been sustained in the cool dark places under the surface. Once I started putting it all together, my only thought was to keep going.

I found the process rich and revelatory. Revisiting the past and working to define my own place in it gave rise to life-altering insight and freedom. What I didn’t know then is that it would take me nearly seven years to write my memoir, and that in the writing I would experience something of a rebirth. That’s what it was for me to finally tell my story—first to myself and now, here, to you, the reader.

I’m fortunate: Few people can afford to review a whole life and find an outlet for their endeavor. I’ve long had a feeling—right or wrong—that I have a unique responsibility to share my experience of the pre-Apple Steve Jobs and to add my perspective to the record. Little is known about Steve as a teenager and young adult. But I knew the young man who was funny and thoughtful. The intellectually honest one who was searching for his place in the world and for what he believed was his big destiny. And I saw firsthand how he changed and changed and changed again as he learned to make use of and misuse power. As such I believe that I have something to say about Steve, also I believe that my reflections as a young woman dealing with systems of power are valuable, too. I suspect that many people will recognize their own stories in some of the details of this book. This and more kept me going, purposeful and inspired.

In the end, what I have written is my story. This is not a tell-all or an exposé, nor is it journalism. This is my own narrative and like all personal narratives, it takes its shape from experience, memory, and insight. I have tried to paint a thoughtful portrait of Steve, of myself, of the time, and of our relationship, and to gain an awareness of things that neither Steve nor I understood when they were happening.

I can say for sure that were it not for the computer, I would never have been able to write this story. But if it weren’t for the computer, I may not have needed to. Such are the simple ironies that have kept me amused throughout the past seven years. (And yes, I did write this on a Mac.)

ONE

THE CREATIVES

I first noticed him in early January of my junior year of high school. It was 1972. He wore thin blue jeans that were full of big holes, the torn material hanging in loops around his legs. He was dressed in a nice pressed shirt and tennis shoes and walked then, as he did as an adult, in a forward-falling gait, arms swinging with a contained reserve in his hands. It was a sunny California afternoon in early spring and he was standing in the quad with a small book in his hand. I don’t know why I hadn’t seen him before, since, as I would find out later, many of my friends knew him. I was drawn to him immediately, and when he walked off campus I followed him, wanting to say something but having no idea what or how. I surprised myself, because I ended up following him out to the edge of the campus three times over the next week. I finally gave up because it was too big a leap for me to introduce myself out of the blue to a boy I thought was cute. I never even learned his name.

A month later my friend and classmate, Mark Izu, started a film project and invited me to do the animation for it. Mark wanted to make a film, combining 2-D animation, Claymation, and actors about how the students at our high school were struggling against forces that we believed wanted to stamp out our individuality. Mark’s parents had been interned in a concentration camp for Japanese in the United States during World War II, and even though he didn’t know this at the time we were making the movie, he was deeply motivated to speak about what it was to be made invisible. We all had our stories. In the course of the project many people would be invited to contribute, but in the beginning it was just three of us: Mark, myself, and a guy named Steve Eckstein, the cameraman.

We worked on the film at least one Friday or Saturday night a week for about three months, starting at 11:00 p.m. and going until dawn. Mark called the film “Hampstead.” A nod to the name of our school—Homestead High School—it was also the name of the stumpy little clay character he made to represent the everyman in the film. Our stage was a raised cement section in the central quad on campus where I usually sat and ate my lunch during the school day. But this was night and we were there without permission, risking God-knows-what if we were caught.

The nights were cold. I was awed by the stars, and I loved that we were out there on our own, making something happen. Our tiny sounds were lost in the expanse of the cavernous, cinder block campus, and it felt like joy to be so focused and quiet, creating something from the margins with that sense of

just we few

. We worked continuously: Mark and Eckstein behind the camera, exchanging quiet words as they filmed; me under a single, brilliant low-angled spotlight. From a semiprone position I drew my designs frame by frame, careful not to draw too little or too much before getting up and stepping back to pause for the frame to be shot, and then returning. This would go on for hours.

On one night, Mark instructed me to build his clay man out of the ground piece by piece so that it looked like Hampstead was emerging from the cement. He then handed me a second Hampstead that he had cut in half, from which I was to start the emergence scene. Once the little guy was fully out of the cement, I made his arms flail in painful insanity from having been buried alive. Another evening I was to draw a pathway for the little figure to walk down. Using cheap colored chalk, I started by illustrating a soft, morphing pattern that enfolded a mutated shape like a flickering fire. It looked psychedelic, but in truth it was drawn from the memory of my parents’ curling cigarette smoke, which I had loved watching as a child in Ohio, just tall enough for my eyes to follow during their monthly poker games with my grandparents.

These were wonderful nights on the Homestead campus and they created a sense of independence and spaciousness in me. If the film was about losing our authenticity, then making it was the antidote. Over time, word got out and people started showing up in twos and threes to see what we were doing. Musicians, cartoonists, late-night stoners, and others joined in, the “Creatives” who represented the gifted and curious Homestead student body. I would look up from my work to see a surprising riot of quiet activity as more and more familiar faces appeared. There was some kind of rare nutrient happiness in all this, and I felt my life filling in around me. By the time the lavender dawn came to end the night, I went home spent, profoundly grateful, and achingly relieved that once again we had not been caught trespassing.

It was maybe a little more than a month into the project when Steve emerged through the darkness and walked straight over to me. I wondered if he’d known that I was interested in him because his path to me was so unerringly direct. But I had told no one. He was tall and beautiful and intentional, a study in contrasts, something like a fine prince in shabby jeans, a little awkward and vulnerable but courageous, too. Behind the small talk we sought out a connection. Then he reached into his pocket and gave me a copy of Bob Dylan’s song “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.” I could feel the indent of the letters as I opened the paper, and I wondered if it was typed for me or if he just happened to have it on him and wanted to share it. I never asked. Later I would come to understand that there was a kind of morphic field around Steve. Things happened; they were uncanny, not particularly planned, but perfect.

We talked for about twenty minutes, long enough for me to observe every minuscule detail about him—the power of his intense eyes and his young sensitivity, the sense that he was just passing through. At the end of our conversation I saw him retreat back into himself, and then with an inexplicably harsh scan of me and the quad—a look that seemed to come from nowhere—he disappeared back into the night.