The Biology of Luck (26 page)

Read The Biology of Luck Online

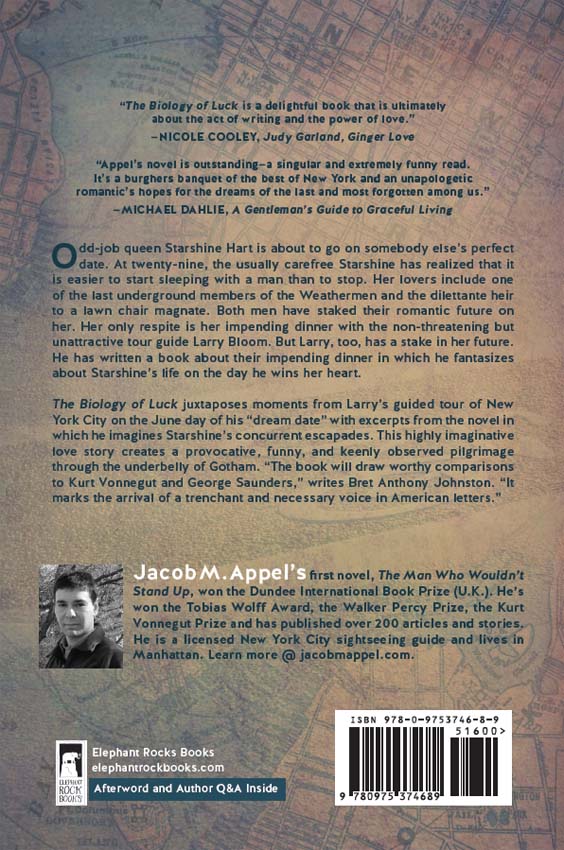

Authors: Jacob M. Appel

Q:

I am charmed by the minor characters in the book: Colby Parker, Snipe, the Armenian florist, Peter Smythe, Ziggy Borasch, Eucalyptus, the list goes on. Each is individually unique and uniquely New York. What was your inspiration for this motley crew? And can you take us through how you created the backstory for Jack Bascomb or Bone?

A:

In case you're reading this novel and you believe these characters are based upon you and the people you know, they're not. Really, they're not. I don't wander around the city looking for interesting people to transform into characters. I sit in my apartment and imagine people whom I wish existed. My building's superintendent is nothing like Bone. Yet on numerous occasions, I've dreamed of a super who could get me anything, like an iron at four a.m. on New Year's Eve, or a copy of Greta Garbo's driver's licenseâand since the managers of my apartment building are unlikely to hire one, I decided to create such a man whole cloth.

Q:

Walt Whitman appears so often in the novel he could be considered a minor character. Early on Starshine imagines “that she is the corporeal incarnation of a Whitman poem.” Later in Battery Park, Larry pays homage to Whitman's statue. You write, “Gazing up into the hero's larger-than-life tribute, the maestro's marble features beaming perpetually over a polished beard, Larry wonders if he has done justice to both master and model.” Whitman is one of the strings that bind them. Can you discuss the long shadow Whitman casts over the novel?

A:

I did not discover Whitman until college. I took a summer class at Columbia with the late, legendary historian James Shentonâ probably New York City's most celebrated tour guideâon “New York City in the Era of Whitman and Melville.” If secular humanists believed in the notion of saints, Whitman would be the patron saint of New York, of hopeless romance, and of wanderingâall of which are at the core of this novel. Anything seems possible after reading a Whitman poemâ¦.

Q:

In an essay entitled “Effective Openings,” you wrote: “In writing, as in dating and business, initial reactions matter. You don't get a second chance, as mouthwash commercials often remind us, to make a first impression.” You submitted

The Biology of Luck

to Elephant Rock Books during an open submission period. (It was not the first book I read, and in fact, it hibernated in the slush pile for three weeks before I thumbed the ink.) But when I did, the prose bounded off the pageâBAM! Minty Fresh! I was sold. Take the opening line of one of the chapters and break it down using your “nine ideas on how to craft a perfect opening line.”

A:

You're asking me to apply what I preach to what I practice, which, as a writer, I find a terrifying prospect; sort of the equivalent of finding out what's in the soup at one's favorite restaurant. But I am grateful my manuscript only hibernated in the slush pile for three weeks. I can't help wondering how many brilliant works of literature

are left to hibernate at the offices of major commercial publishers for decades. I have little doubt there is a prominent literary agent somewhere using the unread draft of a masterwork as a doorstop.

Q:

The genesis of

Biology

is grounded in you being a licensed New York City sightseeing guide. Two questions: How does one become a licensed tour guide? And you've said you wrote the book “to take a shot at creating a convincing and historically grounded paean to the tour guides of NYC.” Why do you think tour guides need convincing and historically grounded paeans?

A:

One becomes a tour guide with great effort. At least back when I earned my license, one had to pass a grueling exam on the history and geography of New York City. I've taken the bar exam and the medical boards, but the NYC tour guide exam is certainly as difficult. And yes, tour guides certainly need a convincing and historically grounded paean. The movies make being a tour guide seem easy and glamorous. In reality, while it's a fascinating experience, it's also hard work.

Q:

Larry and Starshine tour famous landmarks and neighborhoods throughout the five boroughs, exploring what you have called the underbelly of Gotham. If your long-lost Hoosier cousin Tom and his wife Helen were coming to town, where would you take them sightseeing?

A:

My favorite sight in New York is a rather obscure memorial known as the “Amiable Child” monument located on Riverside Drive at 133rd Street. It's the most moving and impressive New York City landmark you've never heard of. I've even written an essay in tribute to the monument that was published several years ago in the

Palo Alto Review

. The monument commemorates the life of Saint Claire Pollock, a child who died in the area in 1797. People in the neighborhood still bring flowers to honor the boy. After 9-11, people left candles and

flowers, and it became a local shrine to suffering and commemoration. It says something wonderful about humanity that we pay our respects as a community to a child we never knew who died two centuries ago. (And if Tom and Helen are reading this, I want to remind them that they should book a hotel room; I don't run a rooming house.)

Q:

If you could break bread with any character from literature, which would it be?

A:

I've always fantasizing of standing up Jordan Baker (from

The Great Gatbsy

) for a date, but I suppose that doesn't count. So I'd have to say Elpinore. As you probably don't recall, he's the fellow in Homer's

Odyssey

who gets drunk and falls off a roof to his death. That's all that we really know of him. Ever since I read the Odyssey in high school, I've wanted to learn the back story. I've also had my dreams of eloping with Ãntonia Shimerda from Willa Cather's

My Antonia

, but what man hasn't?

Q:

The end of the book is open to interpretation. I'm curious what you think happened when Larry and Starshine leave the restaurant? Did Stroop & Stone sign Larry? Does he christen Starshine's new water bed?

A:

Did you really think I'd answer that?

Q:

I thought I might catch you off guard.

A:

All I can promise is that if the book is a success, I'll be glad to write a sequel, or even a series, of Larry and Starshine romances to be sold in airports. But that will require a seven-digit advance.

1.

When we first meet Larry Bloom, he's striding up Broadway, the

New York Times

under his arm and a pack of cigarettes in his shirt pocket, musing about how there should be a civil rights movement for short, relatively unattractive Jewish men. What sort of first impression did this make on you? And how did your impression of Larry change over the course of the book?

2.

What do you make of the André Aciman quote Appel uses as an epigraph? Which characters do you think it applies to? And how does it work in relation to Larry Bloom's novel?

3.

We learn little tidbits of Starshine's personal history throughout the novel, but that history, dramatic as it is, never really gets that much airtime. Did her history surprise you? How did your impression of her evolve as you learned about her past?

4.

Larry Bloom takes us through a good chunk of New York City, peppering his tour group with historical factoids while also trying to protect them from some disconcerting events. How does Appel's New York City strike youâis he going for authenticity or hyperbole, or something in between?

5.

Of the three love interests in Starshine's life (reciprocated or not), which do you think is the most appealing? And which makes the most sense for Starshine?

6.

How important do you think the book-within-a-book structure is to the overall book, and to your enjoyment or frustration as a reader? Can you think of structural comparisons from film, music, or art?

7.

At the end of

chapter one

, Larry tucks the letter from Stroop & Stone into his pocket without reading it. Why did Appel make

this decision? Can you think of a time when you put off finding out important news like that?

8.

How would you classify Appel's writing style? Are there other novelists, or periods, that his voice reminds you of?

9.

Appel has called the book a postmodern love story. In the afterword he explains, “While the structure is âpostmodern' in the spirit of Donald Barthelme or John Barth, that's not what I meant when I wrote of a postmodern love story. Rather, I meant that the love itself is âpostmodern'âhyper-aware, ambivalent, fragmented. That's the world of romance that we live in today.” Has he accurately captured the essence of dating in the twenty-first century? What examples from the book, or your experiences, capture hyper-aware, ambivalent, and fragmented attempts at finding a mate?

10.

Theme

is a reader's word, and

Biology

is full of many of the big themes we find in good fiction. But one theme that Appel clearly establishes is stated at the end of

chapter one

. “He is happy, happy in the way he knows he can be if he wills away the inevitable and succors himself with the remotest of hopes. That is the purpose of his book. That is the subject of his book. That is the reason that the city rises from its slumber.” How is hope represented in the course of events that transpire on this one June day in New York City?

11.

All great art owes something to its predecessors. Appel has said he paralleled parts of his novel after Homer's

Odyssey

and Joyce's

Ulysses

. What links did you discovery between these seminal works and

Biology

?

12.

The most obvious question has to be askedâwhat is Starshine saying yes to, and what is she saying no to? Can you think of other books, or films, that end like this? Does that opened-ended mode work for youâwhy or why not?