The Big Music (48 page)

Authors: Kirsty Gunn

Owing to its isolation from the rest of the country, Sutherland was reputedly the last haunt of the native wolf, the last survivor being shot in the eighteenth century. However, other wildlife has survived, including the golden eagle, sea eagle and pine marten amongst other species which are very rare in the rest of the country. There are pockets of the native Scots Pine, remnants of the original Caledonian Forest.

Sutherland became a local government county, with its own elected county council, in 1890, under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889. At that time, one town within the county, Dornoch, was already well established as an autonomous burgh with its own burgh council. Parish councils, covering rural areas of the county, were established in 1894. The parish councils were abolished in 1931 under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1929 and the county council and the burgh council were abolished in 1975 under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973. The 1973 act also created a new two-tier system, with Sutherland as a district within the Highland region. After 1975 the boundary between the districts of Sutherland and Caithness were slightly redrawn yet retain the shape and spirit of the two counties. Even so, the exact boundaries remain, in the inland areas in particular, in question – their position and lines like the writing of the postal districts on the letters that are sent to and from there, blurred as though by a light Highland rain.

Place names

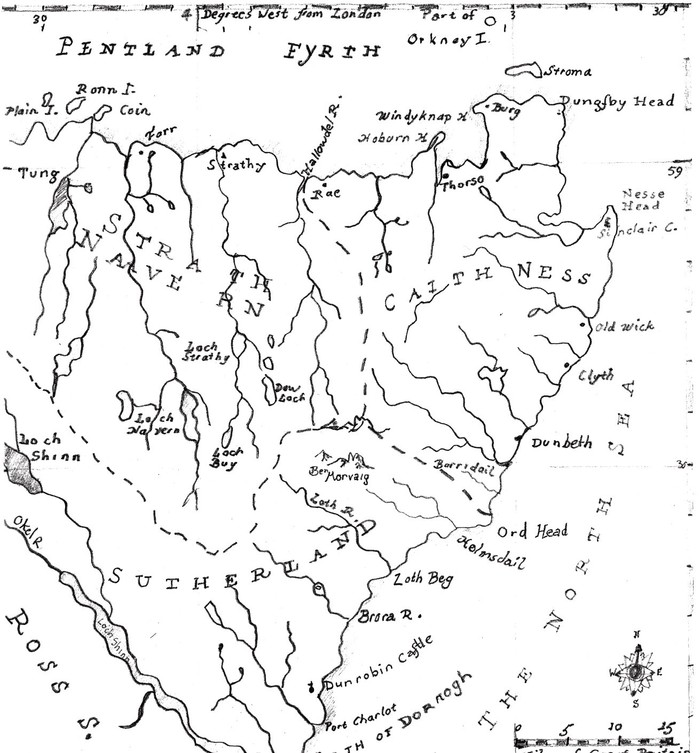

Map showing relevant areas; incl. Mhorvaig; Brora

Domestic life

Up until the mid-nineteenth century most houses in the far North East Region were traditional ‘longhouses’ – that is, a traditional crofthouse comprising two rooms and a middle ‘chamber’ with box beds in both. The byre and barn adjoined that structure, built in a line from it, all single-storey with a thatch roof. A peat fire burned continually for heat and to protect against damp, creating a coat of smoke inside the

dwelling that gave rise to the term ‘blackhouse’ to describe a house of this nature.

A rowan tree was normally planted by the front door to keep away evil spirits – and the doorway and ceiling were low, the whole structure set modestly into the ground with a place for domestic animals set to the back and usually a stone wall running along the front of the property. Practical gardens were maintained, shelter provided by the prudent siting of the house according to the weather and prevailing conditions. For this reason it is rare to come across the remains of a longhouse that is exposed frontwards to the sea, or facing down the strath, or across the water from a hill. Long and low the dwelling places were kept – describing, perhaps, as much as tradition and practicality, a condition of mind and habit.

Yet, while many retained the shape of this house over the years, right up until the beginning of the last century, in fact, others – those who had created slightly larger windows for their homes in the first place, or more flourishing, varied gardens – developed the basic structure and extended it. Most often, this was done by

creating

a first floor that was set into a tiled roof with dormer windows – and many of the standard domestic dwellings of the region to this day still adopt and show this shape – with a porch added to the front and a side structure abutting, often built of wood, or, more recently, corrugated iron.

Life at home over this period – from the eighteenth century’s longhouses to the Victorian era that favoured a more substantial, bourgeois presentation of the

domestic

space – was modest and quiet, with the kitchen featuring at the heart of the domestic world. As the social world altered from one of

ancien régime

to a

replacement

of deference, dependency and loyalty with the values of independence and commercial ambition, so, too, did life at home become more outward-looking and more communally and intellectually engaged.

Families remained large but were more likely to intermingle outside formal events such as ceilidhs and weddings. Visits, one neighbour to another, were made more of; family members expected to do their part entertaining strangers at the door. Where the quiet life of the dark longhouse promoted introspection and clannishness, the lighter, open-looking dwellings of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century celebrated fellowship and community. Children were being educated for longer, and expecting a wider range of employment and social possibilities than a simple return to the family croft. Discussion abounds regarding the self-educating nature of the population at this time for it is clear that over this period, following the deep

conservatism

of the past, the house had become somewhere that was no longer simply a place of shelter and where practicalities were met, but, rather, had become an emblem of domestic life that itself had transformed and could now represent

intellectual

rigour, fresh thought and self-improvement … Change.

i

General background

The Scottish Highlands have been culturally distinguishable from the Scottish

Lowlands

from the later Middle Ages into the modern period, when English replaced Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands and the way of life in the North showed itself to be more set and resistant to agrarian change. Nowhere is this resistance more apparent than in the North East region, where a way of life that was feudal and conservative in character was eventually set upon by agricultural interests that resulted in a redeployment of resources and settlements that came to be known as the Clearances; when that same way of life was dramatically uprooted and its clan system destroyed. Until then the area, like much of the Highlands of Scotland, had remained unchanged since the Middle Ages and before – and indeed, there were certain parts of the North East (in particular Caithness and certain areas of Aberdeenshire and a small portion of Sutherland) that, because of the particular sensibility of their people and a certain flexibility in terms of class definition and the degree of manoeuvrability that could take place within established hierarchal lines, managed to flourish and improve under conditions that were unlike any others that had prevailed in Britain up to that time.

The North East area has always been sparsely populated, with hills and mountains dominating the region, yet for a long period before the nineteenth century was home to a larger population that settled in the sheltered straths and bays and developed strong bonds of community and tithe that went unchanged from one generation to the next. During this period, though other parts of Scotland were being swept up in the innovations brought about by the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution, the North East remained cut off and apart – with lairds and clan chiefs maintaining a way of life that was connected to the communities who worked their land, allowing, in many cases, discrete family groups’ and individuals’ economic and social ambitions to be realised within the prevailing fixities of class and hierarchy. So the area has its own rules, one could say, around this time. It’s different from the rest of Scotland – from both the Catholic West and the more ‘enlightened’ South – and for this reason, for its loneliness, for its isolation, we see a certain independence of character emerging from a particular geographical region. We can see, beneath the rush and tragedy of the story of the Clearances that is to so dominate any narrative of the area, a sense, nevertheless, of autonomy and individualism and stubborn’ness and power.

In general, the era of the Napoleonic Wars, 1790–1815, brought prosperity,

optimism

and economic growth to the Highlands as the economy continued to grow through wages paid by kelping, in fisheries and weaving, as well as large-scale

infrastructure

spending such as the Caledonian Canal project. Where land was improved, high prices could be fetched for cattle and the sheep that at that time were still being husbanded according to traditional methods, yet bought and sold as far away as

Edinburgh

and the South. This, before the great ‘sheepwalks’ that were established after the Clearances, when a flock of Highland ewes raised locally and driven to market in the West and South could bring wealth and security to the community. Service in the Army was also an option for young men who sent pay home and eventually retired there with their army pensions.

By the turn of the century, however, this relative prosperity showed itself to be waning, ending completely after 1815, by which time certain long-run factors had undermined the economic position of the poor tenant farmers or ‘crofters’, as they were called. The adoption by landowners of a market orientation that had started further south in Scotland in the century after 1750 was by now beginning to

dissolve

the traditional social and economic structure of the north-west Highlands and Hebrides Islands, change moving inevitably eastwards with greater efficiency and ruthlessness even to the region that had remained set apart from change for so long. When the Clearances came to Sutherland then, they came hard.

Land use and the Clearances

What became known as the Clearances were considered by the landlords as necessary ‘improvements’. As mentioned above, these ‘improvements’ had started throughout the rest of Scotland in the early part of the eighteenth century when clan chiefs engaged Lowland, or sometimes English, factors with expertise in more profitable sheep farming, and they ‘encouraged’, sometimes forcibly, the population to move off suitable land to other less hospitable areas in the county or, often, to the new colonies abroad.

The year 1792 came to be known as the ‘Year of the Sheep’ to Scottish

Highlanders

and was the beginning of a brutal repatriation that saw those who were

accommodated

in poor crofts or small farms in coastal areas where farming could not sustain the communities off their land and pressed into military service or forced aboard ships bound for Nova Scotia or marched to the cliffheads of Caithness to eke out a living amongst the seaweed and the rocks.

In 1807 Elizabeth Gordon, 19th Countess of Sutherland, was touring her

inheritance

with her husband Lord Stafford when she wrote that ‘he is seized as much as I

am with the rage of improvements, and we both turn our attention with the greatest of energy to turnips’. So change had finally come for this near forgotten part of the kingdom; so change would make its mark. As well as turning land over to sheep farming, Stafford planned to invest in creating a coal-pit, salt-pans, brick- and tileworks and herring fisheries, and that same year his agents began the evictions: ninety families were forced to leave their crops in the ground and move their cattle, sheep, furniture and timbers to the land they were offered twenty miles away on the coast, living in the open until they had built themselves new houses. Stafford’s first commissioner, William Young, arrived in 1809, and soon engaged Patrick Sellar as his factor, who pressed ahead with the process while acquiring sheep-farming estates and establishing for himself the reputation of being one of the most vicious and self-serving administrators of the new regime. Elsewhere, the flamboyant Alexander Ranaldson MacDonell of Glengarry portrayed himself as the last genuine specimen of the true Highland chief while his tenants were subjected to a process of relentless eviction.

See the account below, by Donald MacLeod, a Sutherland crofter, who wrote first-hand of the events he witnessed at that time:

The consternation and confusion were extreme. Little or no time was given for the removal of persons or property; the people striving to remove the sick and the helpless before the fire should reach them; next, struggling to save the most valuable of their effects. The cries of the women and children, the roaring of the affrighted cattle, hunted at the same time by the yelling dogs of the shepherds amid the smoke and fire, altogether presented a scene that completely baffles description – it required to be seen to be believed.

A dense cloud of smoke enveloped the whole country by day, and even extended far out to sea. At night an awfully grand but terrific scene presented itself – all the houses in an extensive district in flames at once. I myself ascended a height about eleven o’clock in the evening, and counted two hundred and fifty blazing houses, many of the owners of which I personally knew, but whose present condition – whether in or out of the flames – I could not tell. The conflagration lasted six days, till the whole of the dwellings were reduced to ashes or smoking ruins. During one of these days a boat actually lost her way in the dense smoke as she approached the shore, but at night was enabled to reach a landing-place by the lurid light of the flames.

In the mid-nineteenth century the second, more brutal phase of the Clearances began – this after the 1822 visit by George IV, when Lowlanders set aside their previous distrust and hatred of the Highlanders and identified with them as national symbols and the entire country once again approached a state of civil war.

Once again a Countess of Sutherland came northwards to visit: Elizabeth Leveson-Gower and her husband George Leveson-Gower. By now evictions were occurring at the rate of, sometimes, two hundred families in one day (this between the period 1811 and 1820) and many starved and froze to death where their homes had once been. The Duchess, on seeing the wretched tenants on her husband’s estate, remarked in a letter to a friend in England, ‘Scotch people are of happier

constitution

and do not fatten like the larger breed of animals.’