The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (35 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

A sketch of the scavenger’s daughter in use.

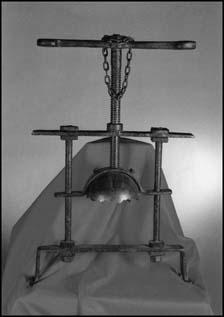

Headcrusher or schneiden.

SCHNEIDEN

As far as we are aware, this is a uniquely German device, first recorded in 1530 and also known as the

Kranz

. It was, in effect, no more and no less than a jaw crushing machine. The

Schneiden

took the form of an iron skullcap held in place by a heavy leather chinstrap. Once in place the strap could be tightened with a ratchet. If pulled tight enough the victim’s teeth were shattered, his jaw broken to pieces and the pressure on the skull became so intense that it felt as though it would explode. To make the pain more unbearable the torture master might amuse himself by tapping on the metal cap with a small hammer.

THUMB SCREWS

This infamous device was designed to place increasing amounts of pressure on the knuckles of both thumbs simultaneously. The victim’s thumbs were inserted into an ‘M’-shaped frame of iron or wood and locked into place by means of a bottom plate which was screwed into place by a small crank or wing nut. As the nut was turned, the lower plate pushed ever harder on thumbs, squeezing them against the top bar of the frame. When the victim agreed to give the right answers the pressure was released; if they refused to cooperate, the pressure could be increased until the knuckles were shattered. In India, a torture similar to the thumb screws was devised, wherein the fingers of the accused were crushed between bamboo rods. Alternatively, the fingers of one hand were bound tightly together with cord and bamboo wedges were driven between the knuckles of the fingers, slicing through flesh, tendon and bone, crushing the knuckles and breaking the fingers.

Thumb screws.

TORTURE BY CUTTING, PIERCING, TEARING AND IMPALING

AMPUTATION

From the dawn of history criminals and enemies of the state have been subjected to having varying parts of their bodies lopped off both as a punishment and as a visible warning to those who would emulate their transgressions. Ears, noses, lips, hands, feet and entire legs have been publicly hacked away, leaving the victim permanently maimed and unable to earn an honest living.

Typical of this practice was medieval France where felons were often sentenced to have their feet amputated; thieves lost their left ear for a first offence, the right for a second and their life for a third. Similarly, under King Louis XII (reigned 1498–1515) anyone found guilty of eight offences of blasphemy had their tongues ripped out. Under English King, Canute (reigned 995–1035) adulterous women had their nose and ears cut off. The most elaborate ceremony associated with corporal amputation came about during the reign of England’s Henry VIII (1509–47).

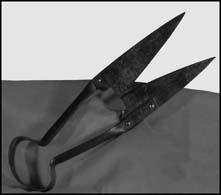

Shears for amputation of digits, ears, noses, tongues, etc.

The Sergant of the Woodyard brought the chopping block and cords with which the prisoner’s hand was to be bound into place. The Master Cook handed the knife to the Sergeant of the Larder who would cut off the offending hand. The Sergeant of Poultry cut off the head of a chicken whose body would be shoved over the stump (apparently to prevent infection), the Yeoman of the Scullery tended the fire where the Sergeant Farrier heated his searing irons. Once the hand had been cut off, the Chief Surgeon took the searing iron from the Sergeant Ferrier and cauterised the wound, the Sergeant of Poultry shoved the dead bird over the stump and the Chief Surgeon bandaged the whole affair. The Sergeant of the Pantry then offered the victim bread while the Sergeant of the Cellar poured him a nice cup of wine. As late as the reign of Good Queen Bess (Elizabeth I, reigned 1558–1603), sheep rustlers had both hands amputated. The practice of corporal amputation was finally outlawed in England in 1820.

Various axes used for dismemberment.

THE BARREL

There is nothing overly fantastical about this devilish contraption. It simply takes the form of a common cask or barrel with long spikes driven into it. The fundamentally simple idea here was that the victim would be placed within the barrel and then rolled down a hill or thrown into the sea. Take for example the martyrdom of Atilius Regulus. It was the year 256 BC; after the great naval victory of Ecnomos, for the Roman consul Marcus Atilius Regulus there seemed to be no further obstacles to the capture of Carthage. Unfortunately the Battle of Tunis was a disaster for the Roman legions and the consul was captured by the Punic Army. After languishing as a prisoner of the Carthaginians for five years, it was decided that he could return to his homeland to negotiate a peace between Rome and Carthage, dependent upon a promise to return as a prisoner if the negotiations failed. Despite the convictions of the Carthaginians, who felt sure of the collaboration of a man destroyed by years of slavery who would plead their cause, in a famous session of the Senate, Atilius Regulus urged the Romans to fight strenuously against the enemy and reject peace. Having achieved his objective, he did not ignore his word to the enemy and, despite the pleading of the Roman people, returned to Africa where he awaited their cruel vengeance.

Spiked barrel.

Execution of Atilius Regulus.

Tradition has it that the full fury of the Carthaginians fell upon the heroic military leader. He was confined in complete darkness for at least a week whilst awaiting execution, then his eyelids were cut off as he was exposed to the baking north African sun; finally he was placed naked in a barrel with iron spikes on the inside, sealed up, and then thrown from a cliff into the raging surf of the sea below.

BEHEADING

Hacking off an enemy’s head is as old as the axe, but the custom of judicial beheading was probably established by William the Conqueror when he seized control of England in 1066. Since William executed his Anglo-Saxon subjects on a massive scale, he decided he needed a different – and presumably more noble – way to execute his Norman followers who fell afoul of royal law. Hence, the block and axe. From 1066 until it was abolished in the mid-1700s, meeting the headsman was the death of choice for naughty British and European nobility. The English and Germans used the axe and the French used a sword, but the results were pretty much the same, though it is reported that a nice sharp sword was a lot swifter and less messy than the often botched job done with the axe. Even James II’s notorious headsman, Jack Ketch, was known to take three of four chops to get the job done. There were, of course, an endless string of innovators who attempted to make the process more efficient. Around 1300 the Germans invented a beheading machine. Precisely what it looked like is unknown, but it must have been successful as it was quickly imitated by the Italians, the Irish and the English. The English device, constructed around the middle of the fourteenth century in Halifax, North Yorkshire, was known as the Halifax Gibbet, although it was not in any way like the gibbet described elsewhere in this chapter. According to historical records, the Halifax Gibbet was still in use more than a century later when the idea was carried to Scotland. The most famous beheading machine in history is unquestionably the guillotine.