The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (76 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Amazon.com, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Social History, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

11.51Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Rummel was one of the first advocates of the Democratic Peace theory, which he argues applied to democides even more than to wars. “At the extremes of Power,” Rummel writes, “totalitarian communist governments slaughter their people by the tens of

millions;

in contrast, many democracies can barely bring themselves to execute even serial murderers.”

156

Democracies commit fewer democides because their form of governance, by definition, is committed to inclusive and nonviolent means of resolving conflicts. More important, the power of a democratic government is restricted by a tangle of institutional restraints, so a leader can’t just mobilize armies and militias on a whim to fan out over the country and start killing massive numbers of citizens. By performing a set of regressions on his dataset of 20th-century regimes, Rummel showed that the occurrence of democide correlates with a lack of democracy, even holding constant the countries’ ethnic diversity, wealth, level of development, population density, and culture (African, Asian, Latin American, Muslim, Anglo, and so on).

157

The lessons, he writes, are clear: “The problem is Power. The solution is democracy. The course of action is to foster freedom.”

158

millions;

in contrast, many democracies can barely bring themselves to execute even serial murderers.”

156

Democracies commit fewer democides because their form of governance, by definition, is committed to inclusive and nonviolent means of resolving conflicts. More important, the power of a democratic government is restricted by a tangle of institutional restraints, so a leader can’t just mobilize armies and militias on a whim to fan out over the country and start killing massive numbers of citizens. By performing a set of regressions on his dataset of 20th-century regimes, Rummel showed that the occurrence of democide correlates with a lack of democracy, even holding constant the countries’ ethnic diversity, wealth, level of development, population density, and culture (African, Asian, Latin American, Muslim, Anglo, and so on).

157

The lessons, he writes, are clear: “The problem is Power. The solution is democracy. The course of action is to foster freedom.”

158

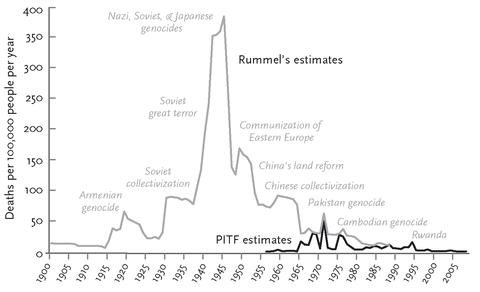

What about the historical trajectory? Rummel tried to break down his 20th-century democides by year, and I’ve reproduced his data, scaled by world population, in the gray upper line in figure 6–7. Like deaths in wars, deaths in democides were concentrated in a savage burst, the midcentury Hemoclysm.

159

This blood-flood embraced the Nazi Holocaust, Stalin’s purges, the Japanese rape of China and Korea, and the wartime firebombings of cities in Europe and Japan. The left slope also includes the Armenian genocide during World War I and the Soviet collectivization campaign, which killed millions of Ukrainians and kulaks, the so-called rich peasants. The right slope embraces the killing of millions of ethnic Germans in newly communized Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania, and the victims of forced collectivization in China. It’s uncomfortable to say that there’s anything good in the trends shown in the graph, but in an important sense there is. The world has seen nothing close to the bloodletting of the 1940s since then; in the four decades that followed, the rate (and number) of deaths from democide went precipitously, if lurchingly, downward. (The smaller bulges represent killings by Pakistani forces during the Bangladesh war of independence in 1971 and by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia in the late 1970s.) Rummel attributes the falloff in democide since World War II to the decline of totalitarianism and the rise of democracy.

160

159

This blood-flood embraced the Nazi Holocaust, Stalin’s purges, the Japanese rape of China and Korea, and the wartime firebombings of cities in Europe and Japan. The left slope also includes the Armenian genocide during World War I and the Soviet collectivization campaign, which killed millions of Ukrainians and kulaks, the so-called rich peasants. The right slope embraces the killing of millions of ethnic Germans in newly communized Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania, and the victims of forced collectivization in China. It’s uncomfortable to say that there’s anything good in the trends shown in the graph, but in an important sense there is. The world has seen nothing close to the bloodletting of the 1940s since then; in the four decades that followed, the rate (and number) of deaths from democide went precipitously, if lurchingly, downward. (The smaller bulges represent killings by Pakistani forces during the Bangladesh war of independence in 1971 and by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia in the late 1970s.) Rummel attributes the falloff in democide since World War II to the decline of totalitarianism and the rise of democracy.

160

FIGURE 6–7.

Rate of deaths in genocides, 1900–2008

Rate of deaths in genocides, 1900–2008

Sources:

Data for the gray line, 1900–1987, from Rummel, 1997. Data for the black line, 1955–2008, from the Political Instability Task Force (PITF) State Failure Problem Set, 1955–2008, Marshall, Gurr, & Harff, 2009; Center for Systemic Peace, 2010. The death tolls for the latter were geometric means of the ranges in table 8.1 in Harff, 2005, distributed across years according to the proportions in the Excel database. World population figures from U.S. Census Bureau, 2010c. Population figures for the years 1900–1949 were taken from McEvedy & Jones, 1978, and multiplied by 1.01 to make them commensurable with the rest.

Data for the gray line, 1900–1987, from Rummel, 1997. Data for the black line, 1955–2008, from the Political Instability Task Force (PITF) State Failure Problem Set, 1955–2008, Marshall, Gurr, & Harff, 2009; Center for Systemic Peace, 2010. The death tolls for the latter were geometric means of the ranges in table 8.1 in Harff, 2005, distributed across years according to the proportions in the Excel database. World population figures from U.S. Census Bureau, 2010c. Population figures for the years 1900–1949 were taken from McEvedy & Jones, 1978, and multiplied by 1.01 to make them commensurable with the rest.

Rummel’s dataset ends in 1987, just when things start to get interesting again. Soon communism fell and democracies proliferated—and the world was hit with the unpleasant surprise of genocides in Bosnia and Rwanda. In the impression of many observers, these “new wars” show that we are still living, despite all we should have learned, in an age of genocide.

The historical thread of genocide statistics has recently been extended by the political scientist Barbara Harff. During the Rwanda genocide, some 700,000 Tutsis were killed in just four months by about 10,000 men with machetes, many of them drunkards, addicts, ragpickers, and gang members hastily recruited by the Hutu leadership.

161

Many observers believe that this small pack of

génocidaires

could easily have been stopped by a military intervention by the world’s great powers.

162

Bill Clinton in particular was haunted by his own failure to act, and in 1998 he commissioned Harff to analyze the risk factors and warning signs of genocide.

163

She assembled a dataset of 41 genocides and politicides between 1955 (shortly after Stalin died and the process of decolonization began) and 2004. Her criteria were more restrictive than Rummel’s and closer to Lemkin’s original definition of genocide: episodes of violence in which a state or armed authority intends to destroy, in whole or in part, an identifiable group. Only five of the episodes turned out to be “genocide” in the sense in which people ordinarily understand the term, namely an ethnocide, in which a group is singled out for destruction because of its ethnicity. Most were politicides, or politicides combined with ethnocides, in which members of an ethnic group were thought to be aligned with a targeted political faction.

161

Many observers believe that this small pack of

génocidaires

could easily have been stopped by a military intervention by the world’s great powers.

162

Bill Clinton in particular was haunted by his own failure to act, and in 1998 he commissioned Harff to analyze the risk factors and warning signs of genocide.

163

She assembled a dataset of 41 genocides and politicides between 1955 (shortly after Stalin died and the process of decolonization began) and 2004. Her criteria were more restrictive than Rummel’s and closer to Lemkin’s original definition of genocide: episodes of violence in which a state or armed authority intends to destroy, in whole or in part, an identifiable group. Only five of the episodes turned out to be “genocide” in the sense in which people ordinarily understand the term, namely an ethnocide, in which a group is singled out for destruction because of its ethnicity. Most were politicides, or politicides combined with ethnocides, in which members of an ethnic group were thought to be aligned with a targeted political faction.

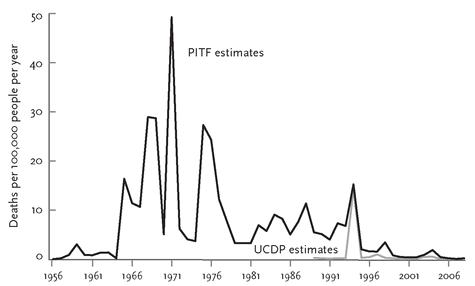

In figure 6–7 I plotted Harff’s PITF data on the same axes with Rummel’s. Her figures generally come in well below his, especially in the late 1950s, for which she included far fewer victims of the executions during the Great Leap Forward. But thereafter the curves show similar trends, which are downward from their peak in 1971. Because the genocides from the second half of the 20th century were so much less destructive than those of the Hemoclysm, I’ve zoomed in on her curve in figure 6–8. The graph also shows the death rates in a third collection, the UCDP One-Sided Violence Dataset, which includes any instance of a government or other armed authority killing at least twenty-five civilians in a year; the perpetrators need not intend to destroy the group per se.

164

164

The graph shows that the two decades since the Cold War have

not

seen a recrudescence of genocide. On the contrary, the peak in mass killing (putting aside China in the 1950s) is located in the mid-1960s to late 1970s. Those fifteen years saw a politicide against communists in Indonesia (1965–66, “the year of living dangerously,” with 700,000 deaths), the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–75, around 600,000), Tutsis against Hutus in Burundi (1965–73, 140,000), Pakistan’s massacre in Bangladesh (1971, around 1.7 million), north-againstsouth violence in Sudan (1956–72, around 500,000), Idi Amin’s regime in Uganda (1972–79, around 150,000), the Cambodian madness (1975–79, 2.5 million), and a decade of massacres in Vietnam culminating in the expulsion of the boat people (1965–75, around half a million).

165

The two decades since the end of the Cold War have been marked by genocides in Bosnia from 1992 to 1995 (225,000 deaths), Rwanda (700,000 deaths), and Darfur (373,000 deaths from 2003 to 2008). These are atrocious numbers, but as the graph shows, they are spikes in a trend that is unmistakably downward. (Recent studies have shown that even some of these figures may be overestimates, but I will stick with the datasets.)

166

The first decade of the new millennium is the most genocide-free of the past fifty years. The UCDP numbers are restricted to a narrower time window and, like all their estimates, are more conservative, but they show a similar pattern: the Rwanda genocide in 1994 leaps out from all the other episodes of one-sided killing, and the world has seen nothing like it since.

not

seen a recrudescence of genocide. On the contrary, the peak in mass killing (putting aside China in the 1950s) is located in the mid-1960s to late 1970s. Those fifteen years saw a politicide against communists in Indonesia (1965–66, “the year of living dangerously,” with 700,000 deaths), the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–75, around 600,000), Tutsis against Hutus in Burundi (1965–73, 140,000), Pakistan’s massacre in Bangladesh (1971, around 1.7 million), north-againstsouth violence in Sudan (1956–72, around 500,000), Idi Amin’s regime in Uganda (1972–79, around 150,000), the Cambodian madness (1975–79, 2.5 million), and a decade of massacres in Vietnam culminating in the expulsion of the boat people (1965–75, around half a million).

165

The two decades since the end of the Cold War have been marked by genocides in Bosnia from 1992 to 1995 (225,000 deaths), Rwanda (700,000 deaths), and Darfur (373,000 deaths from 2003 to 2008). These are atrocious numbers, but as the graph shows, they are spikes in a trend that is unmistakably downward. (Recent studies have shown that even some of these figures may be overestimates, but I will stick with the datasets.)

166

The first decade of the new millennium is the most genocide-free of the past fifty years. The UCDP numbers are restricted to a narrower time window and, like all their estimates, are more conservative, but they show a similar pattern: the Rwanda genocide in 1994 leaps out from all the other episodes of one-sided killing, and the world has seen nothing like it since.

FIGURE 6–8.

Rate of deaths in genocides, 1956–2008

Rate of deaths in genocides, 1956–2008

Sources:

PITF estimates, 1955–2008: same as for figure 6–7. UCDP, 1989–2007: “High Fatality” estimates from

http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/datasets/

(Kreutz, 2008; Kristine & Hultman, 2007) divided by world population from U.S. Census Bureau, 2010c.

PITF estimates, 1955–2008: same as for figure 6–7. UCDP, 1989–2007: “High Fatality” estimates from

http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/datasets/

(Kreutz, 2008; Kristine & Hultman, 2007) divided by world population from U.S. Census Bureau, 2010c.

Harff was tasked not just with compiling genocides but with identifying their risk factors. She noted that virtually all of them took place in the aftermath of a state failure such as a civil war, revolution, or coup. So she assembled a control group with 93 cases of state failure that did

not

result in genocide, matched as closely as possible to the ones that did, and ran a logistic regression analysis to find out which aspects of the situation the year before made the difference.

not

result in genocide, matched as closely as possible to the ones that did, and ran a logistic regression analysis to find out which aspects of the situation the year before made the difference.

Some factors that one might think were important turned out not to be. Measures of ethnic diversity didn’t matter, refuting the conventional wisdom that genocides represent the eruption of ancient hatreds that inevitably explode when ethnic groups live side by side. Nor did measures of economic development matter. Poor countries are more likely to have political crises, which are necessary conditions for genocides to take place, but among the countries that did have crises, the poorer ones were no more likely to sink into actual genocide.

Harff did discover six risk factors that distinguished the genocidal from the nongenocidal crises in three-quarters of the cases.

167

One was a country’s previous history of genocide, presumably because whatever risk factors were in place the first time did not vanish overnight. The second predictor was the country’s immediate history of political instability—to be exact, the number of regime crises and ethnic or revolutionary wars it had suffered in the preceding fifteen years. Governments that feel threatened are tempted to eliminate or take revenge on groups they perceive to be subversive or contaminating, and are more likely to exploit the ongoing chaos to accomplish those goals before opposition can mobilize.

168

A third was a ruling elite that came from an ethnic minority, presumably because that multiplies the leaders’ worries about the precariousness of their rule.

167

One was a country’s previous history of genocide, presumably because whatever risk factors were in place the first time did not vanish overnight. The second predictor was the country’s immediate history of political instability—to be exact, the number of regime crises and ethnic or revolutionary wars it had suffered in the preceding fifteen years. Governments that feel threatened are tempted to eliminate or take revenge on groups they perceive to be subversive or contaminating, and are more likely to exploit the ongoing chaos to accomplish those goals before opposition can mobilize.

168

A third was a ruling elite that came from an ethnic minority, presumably because that multiplies the leaders’ worries about the precariousness of their rule.

The other three predictors are familiar from the theory of the Liberal Peace. Harff vindicated Rummel’s insistence that democracy is a key factor in preventing genocides. From 1955 to 2008 autocracies were three and a half times more likely to commit genocides than were full or partial democracies, holding everything else constant. This represents a hat trick for democracy: democracies are less likely to wage interstate wars, to have large-scale civil wars, and to commit genocides. Partial democracies (anocracies) are more likely than autocracies to have violent political crises, as we saw in Fearon and Laitin’s analysis of civil wars, but when a crisis does occur, the partial democracies are less likely than autocracies to become genocidal.

Another trifecta was scored by openness to trade. Countries that depend more on international trade, Harff found, are less likely to commit genocides, just as they are less likely to fight wars with other countries and to be riven by civil wars. The inoculating effects of trade against genocide cannot depend, as they do in the case of interstate war, on the positive-sum benefits of trade itself, since the trade we are talking about (imports and exports) does not consist in exchanges with the vulnerable ethnic or political groups. Why, then, should trade matter? One possibility is that Country A might take a communal or moral interest in a group living within the borders of Country B. If B wants to trade with A, it must resist the temptation to exterminate that group. Another is that a desire to engage in trade requires certain peaceable attitudes, including a willingness to abide by international norms and the rule of law, and a mission to enhance the material welfare of its citizens rather than implementing a vision of purity, glory, or perfect justice.

The last predictor of genocide is an exclusionary ideology. Ruling elites that are under the spell of a vision that identifies a certain group as the obstacle to an ideal society, putting it “outside the sanctioned universe of obligation,” are far more likely to commit genocide than elites with a more pragmatic or eclectic governing philosophy. Exclusionary ideologies, in Harff’s classification, include Marxism, Islamism (in particular, a strict application of Sharia law), militaristic anticommunism, and forms of nationalism that demonize ethnic or religious rivals.

Other books

Broken Vision by J.A. Clarke

The Shining Company by Rosemary Sutcliff

China 1945: Mao's Revolution and America's Fateful Choice by Richard Bernstein

Spice and Smoke by Suleikha Snyder

The Greek & Latin Roots of English by Tamara M. Green

Shirley Jones by Shirley Jones

The Only Shark In The Sea (The Date Shark Series Book 3) by Gladden, Delsheree

Human Remains by Elizabeth Haynes

Sky Knife by Marella Sands

Blazing Earth by TERRI BRISBIN