The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (40 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

4.81Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

FIGURE 4–8.

Efficiency in book production in England, 1470–1860s

Efficiency in book production in England, 1470–1860s

Source:

Graph from Clark, 2007a, p. 253.

Graph from Clark, 2007a, p. 253.

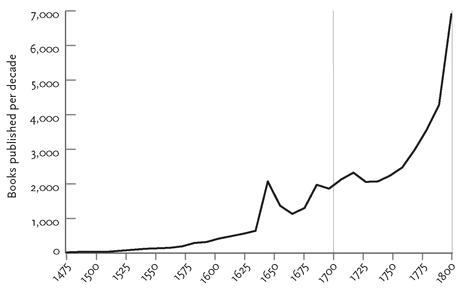

FIGURE 4–9.

Number of books in English published per decade, 1475–1800

Number of books in English published per decade, 1475–1800

Sources:

Simons, 2001; graph adapted from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File1477-1799_ESTC_titles_per_decade,_statistics.png

:.

Simons, 2001; graph adapted from

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File1477-1799_ESTC_titles_per_decade,_statistics.png

:.

The newly efficient publishing technology set off an explosion in book publication. Figure 4–9 shows that the number of books published per year rose significantly in the 17th century and shot up toward the end of the 18th.

The books, moreover, were not just playthings for aristocrats and intellectuals. As the literary scholar Suzanne Keen notes, “By the late 18th century, circulating libraries had become widespread in London and provincial towns, and most of what they offered for rent was novels.”

131

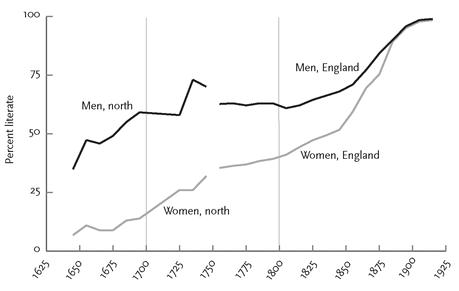

With more numerous and cheaper books available, people had a greater incentive to read. It’s not easy to estimate the level of literacy in periods before the advent of universal schooling and standardized testing, but historians have used clever proxy measures such as the proportion of people who could sign their marriage registers or court declarations. Figure 4–10 presents a pair of time series from Clark which suggest that during the 17th century in England, rates of literacy doubled, and that by the end of the century a majority of Englishmen had learned to read and write.

132

131

With more numerous and cheaper books available, people had a greater incentive to read. It’s not easy to estimate the level of literacy in periods before the advent of universal schooling and standardized testing, but historians have used clever proxy measures such as the proportion of people who could sign their marriage registers or court declarations. Figure 4–10 presents a pair of time series from Clark which suggest that during the 17th century in England, rates of literacy doubled, and that by the end of the century a majority of Englishmen had learned to read and write.

132

Literacy was increasing in other parts of Western Europe at the same time. By the late 18th century a majority of French citizens had become literate, and though estimates of literacy don’t appear for other countries until later, they suggest that by the early 19th century a majority of men were literate in Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Scotland, Sweden, and Switzerland as well.

133

Not only were more people reading, but they were reading in different ways, a development the historian Rolf Engelsing has called the Reading Revolution.

134

People began to read secular rather than just religious material, to read to themselves instead of in groups, and to read a wide range of topical media, such as pamphlets and periodicals, rather than rereading a few canonical texts like almanacs, devotional works, and the Bible. As the historian Robert Darnton put it, “The late eighteenth century does seem to represent a turning point, a time when more reading matter became available to a wider public, when one can see the emergence of a mass readership that would grow to giant proportions in the nineteenth century with the development of machine-made paper, steam-powered presses, linotype, and nearly universal literacy.”

135

133

Not only were more people reading, but they were reading in different ways, a development the historian Rolf Engelsing has called the Reading Revolution.

134

People began to read secular rather than just religious material, to read to themselves instead of in groups, and to read a wide range of topical media, such as pamphlets and periodicals, rather than rereading a few canonical texts like almanacs, devotional works, and the Bible. As the historian Robert Darnton put it, “The late eighteenth century does seem to represent a turning point, a time when more reading matter became available to a wider public, when one can see the emergence of a mass readership that would grow to giant proportions in the nineteenth century with the development of machine-made paper, steam-powered presses, linotype, and nearly universal literacy.”

135

FIGURE 4–10.

Literacy rate in England, 1625–1925

Literacy rate in England, 1625–1925

Source:

Graph adapted from Clark, 2007a, p. 179.

Graph adapted from Clark, 2007a, p. 179.

And of course people in the 17th and 18th centuries had more to read about. The Scientific Revolution had revealed that everyday experience is a narrow slice of a vast continuum of scales from the microscopic to the astronomical, and that our own abode is a rock orbiting a star rather than the center of creation. The European exploration of the Americas, Oceania, and Africa, and the discovery of sea routes to India and Asia, had opened up new worlds and revealed the existence of exotic peoples with ways of life very different from the readers’ own.

The growth of writing and literacy strikes me as the best candidate for an exogenous change that helped set off the Humanitarian Revolution. The pokey little world of village and clan, accessible through the five senses and informed by a single content provider, the church, gave way to a phantasmagoria of people, places, cultures, and ideas. And for several reasons, the expansion of people’s minds could have added a dose of humanitarianism to their emotions and their beliefs.

THE RISE OF EMPATHY AND THE REGARD FOR HUMAN LIFEThe human capacity for compassion is not a reflex that is triggered automatically by the presence of another living thing. As we shall see in chapter 9, though people in all cultures can react sympathetically to kin, friends, and babies, they tend to hold back when it comes to larger circles of neighbors, strangers, foreigners, and other sentient beings. In his book

The Expanding Circle

, the philosopher Peter Singer has argued that over the course of history, people have enlarged the range of beings whose interests they value as they value their own.

136

An interesting question is what inflated the empathy circle. And a good candidate is the expansion of literacy.

The Expanding Circle

, the philosopher Peter Singer has argued that over the course of history, people have enlarged the range of beings whose interests they value as they value their own.

136

An interesting question is what inflated the empathy circle. And a good candidate is the expansion of literacy.

Reading is a technology for perspective-taking. When someone else’s thoughts are in your head, you are observing the world from that person’s vantage point. Not only are you taking in sights and sounds that you could not experience firsthand, but you have stepped inside that person’s mind and are temporarily sharing his or her attitudes and reactions. As we shall see, “empathy” in the sense of adopting someone’s viewpoint is not the same as “empathy” in the sense of feeling compassion toward the person, but the first can lead to the second by a natural route. Stepping into someone else’s vantage point reminds you that the other fellow has a first-person, present-tense, ongoing stream of consciousness that is very much like your own but not the same as your own. It’s not a big leap to suppose that the habit of reading other people’s words could put one in the habit of entering other people’s minds, including their pleasures and pains. Slipping even for a moment into the perspective of someone who is turning black in a pillory or desperately pushing burning faggots away from her body or convulsing under the two hundredth stroke of the lash may give a person second thoughts as to whether these cruelties should ever be visited upon anyone.

Adopting other people’s vantage points can alter one’s convictions in other ways. Exposure to worlds that can be seen only through the eyes of a foreigner, an explorer, or a historian can turn an unquestioned norm (“That’s the way it’s done”) into an explicit observation (“That’s what our tribe happens to do now”). This self-consciousness is the first step toward asking whether the practice could be done in some other way. Also, learning that over the course of history the first can become last and the last can become first may instill the habit of mind that reminds us, “There but for fortune go I.”

The power of literacy to lift readers out of their parochial stations is not confined to factual writing. We have already seen how satirical fiction, which transports readers into a hypothetical world from which they can observe the follies of their own, may be an effective way to change people’s sensibilities without haranguing or sermonizing.

Realistic fiction, for its part, may expand readers’ circle of empathy by seducing them into thinking and feeling like people very different from themselves. Literature students are taught that the 18th century was a turning point in the history of the novel. It became a form of mass entertainment, and by the end of the century almost a hundred new novels were published in England and France every year.

137

And unlike earlier epics which recounted the exploits of heroes, aristocrats, or saints, the novels brought to life the aspirations and losses of ordinary people.

137

And unlike earlier epics which recounted the exploits of heroes, aristocrats, or saints, the novels brought to life the aspirations and losses of ordinary people.

Lynn Hunt points out that the heyday of the Humanitarian Revolution, the late 18th century, was also the heyday of the epistolary novel. In this genre the story unfolds in a character’s own words, exposing the character’s thoughts and feelings in real time rather than describing them from the distancing perspective of a disembodied narrator. In the middle of the century three melodramatic novels named after female protagonists became unlikely bestsellers: Samuel Richardson’s

Pamela

(1740) and

Clarissa

(1748), and Rousseau’s

Julie, or the New Hélöise

(1761). Grown men burst into tears while experiencing the forbidden loves, intolerable arranged marriages, and cruel twists of fate in the lives of undistinguished women (including servants) with whom they had nothing in common. A retired military officer, writing to Rousseau, gushed:

Pamela

(1740) and

Clarissa

(1748), and Rousseau’s

Julie, or the New Hélöise

(1761). Grown men burst into tears while experiencing the forbidden loves, intolerable arranged marriages, and cruel twists of fate in the lives of undistinguished women (including servants) with whom they had nothing in common. A retired military officer, writing to Rousseau, gushed:

You have driven me crazy about her. Imagine then the tears that her death must have wrung from me. . . . Never have I wept such delicious tears. That reading created such a powerful effect on me that I believe I would have gladly died during that supreme moment.

138

The philosophes of the Enlightenment extolled the way novels engaged a reader’s identification with and sympathetic concern for others. In his eulogy for Richardson, Diderot wrote:

One takes, despite all precautions, a role in his works, you are thrown into conversation, you approve, you blame, you admire, you become irritated, you feel indignant. How many times did I not surprise myself, as it happens to children who have been taken to the theater for the first time, crying: “Don’t believe it, he is deceiving you.”. . . His characters are taken from ordinary society . . . the passions he depicts are those I feel in myself.

139

The clergy, of course, denounced these novels and placed several on the Index of Forbidden Books. One Catholic cleric wrote, “Open these works and you will see in almost all of them the rights of divine and human justice violated, parents’ authority over their children scorned, the sacred bonds of marriage and friendship broken.”

140

140

Hunt suggests a causal chain: reading epistolary novels about characters unlike oneself exercises the ability to put oneself in other people’s shoes, which turns one against cruel punishments and other abuses of human rights. As usual, it is hard to rule out alternative explanations for the correlation. Perhaps people became more empathic for other reasons, which simultaneously made them receptive to epistolary novels and concerned with others’ mistreatment.

But the full-strength causal hypothesis may be more than a fantasy of English teachers. The ordering of events is in the right direction: technological advances in publishing, the mass production of books, the expansion of literacy, and the popularity of the novel all preceded the major humanitarian reforms of the 18th century. And in some cases a bestselling novel or memoir demonstrably exposed a wide range of readers to the suffering of a forgotten class of victims and led to a change in policy. Around the same time that

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

mobilized abolitionist sentiment in the United States, Charles Dickens’s

Oliver Twist

(1838) and

Nicholas Nickleby

(1839) opened people’s eyes to the mistreatment of children in British workhouses and orphanages, and Richard Henry Dana’s

Two Years Before the Mast: A Personal Narrative of Life at Sea

(1840) and Herman Melville’s

White Jacket

helped end the flogging of sailors. In the past century Erich Maria Remarque’s

All Quiet on the Western Front

, George Orwell’s

1984,

Arthur Koestler’s

Darkness at Noon

, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

, Harper Lee’s

To Kill a Mockingbird

, Elie Wiesel’s

Night

, Kurt Vonnegut’s

Slaughterhouse-Five

, Alex Haley’s

Roots

, Anchee Min’s

Red Azalea

, Azar Nafisi’s

Reading Lolita in Tehran

, and Alice Walker’s

Possessing the Secret of Joy

(a novel that features female genital mutilation) all raised public awareness of the suffering of people who might otherwise have been ignored.

141

Cinema and television reached even larger audiences and offered experiences that were even more immediate. In chapter 9 we will learn of experiments that confirm that fictional narratives can evoke people’s empathy and prick them to action.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

mobilized abolitionist sentiment in the United States, Charles Dickens’s

Oliver Twist

(1838) and

Nicholas Nickleby

(1839) opened people’s eyes to the mistreatment of children in British workhouses and orphanages, and Richard Henry Dana’s

Two Years Before the Mast: A Personal Narrative of Life at Sea

(1840) and Herman Melville’s

White Jacket

helped end the flogging of sailors. In the past century Erich Maria Remarque’s

All Quiet on the Western Front

, George Orwell’s

1984,

Arthur Koestler’s

Darkness at Noon

, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

, Harper Lee’s

To Kill a Mockingbird

, Elie Wiesel’s

Night

, Kurt Vonnegut’s

Slaughterhouse-Five

, Alex Haley’s

Roots

, Anchee Min’s

Red Azalea

, Azar Nafisi’s

Reading Lolita in Tehran

, and Alice Walker’s

Possessing the Secret of Joy

(a novel that features female genital mutilation) all raised public awareness of the suffering of people who might otherwise have been ignored.

141

Cinema and television reached even larger audiences and offered experiences that were even more immediate. In chapter 9 we will learn of experiments that confirm that fictional narratives can evoke people’s empathy and prick them to action.

Other books

The Fiery Ring by Gilbert Morris

Left for Dead by J.A. Jance

Andrew North Blows Up the World by Adam Selzer

Then You Happened by Sandi Lynn

Jeremy (Broken Angel #4) by L. G. Castillo

Life After: Episode 4 (A Serial Novel) by Holden, JJ

Fallout by Ariel Tachna

Futanarium 1: An Erotic Short Story Bundle by Maria N. Lang

Blood Ties by C.C. Humphreys

Eternal Service by Regina Morris