The Beasts that Hide from Man (39 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

As discussed elsewhere (Shuker, 1995f), based upon recent paleontological discoveries and theories the present author considers that a plesiosaur identity offers greater morphological and behavioral correspondence with long-necked sea serpents (and their freshwater counterparts) than does Heuvelmans’s hypothetical long-necked seal

Megalotaria longicollis

.

Heuvelmans nominated an armored, scaly archaeocete as the identity of his many-finned sea serpent

Cetioscolopendra aeliani

(Heuvelmans, 1968). However, it is now known that scales found in association with certain specimens of fossil archaeocete did not originate from them (as originally assumed), but belonged instead to various other creatures. In other words, there are no verified specimens of armored archaeocetes in the fossil record, thereby greatly reducing the likelihood of any modern-day species existing (Shuker, 1995f).

One of the most significant reports supporting the reality of Heuvelmans’s Scandinavian super-otter

Hyperhydra egedei

(Heuvelmans, 1968) originateci with a sighting off the coast of Greenland made on July 6, 1734, by a priest, Hans Egede (in honor of whom Heuvelmans named the super-otter) and his son Poul. However, Danish zoologist Lars Thomas recently published, for the first time in any cryptozoological document, the original description of this creature, as penned separately by Hans and Poul Egede (Thomas, 1996), which reveals the creature to be very different morphologically from the super-otter envisaged by Heuvelmans. As a result, Thomas concludes: “It is so different, in fact, that I would suggest it is an entirely different animal to the super-otters Heuvelmans records as having been seen along the coast of Norway. Perhaps they should then be called the Norwegian super-otter

(Hyperhydra norvegica);

certainly not Egede’s super-otter” (Thomas, 1996).

A giant undiscovered species of swamp-dwelling lungfish inhabiting the Apa Tani’s remote upland valley in northern Assam, India, has been nominated as a more compatible alternative to a monitor lizard for the identity of the

bum

(Izzard, 1951; Shuker, 1991b).

In his original checklist, Heuvelmans claimed that the

minhocão

was presumably an amphibious burrowing mammal (Heuvelmans, 1986), and had previously specified a surviving glyptodont as a contender for this identity (Heuvelmans, 1958). However, as proposed by the present author, an extremely large species of caecilian would provide a much closer morphological and behavioral correspondence with this cryptid (Shuker, 1995f); Heuvelmans also favored a fossorial amphibian in his updated checklist (Heuvelmans, 1996).

Heuvelmans’s list opined that the

migo

of Lake Dakataua in New Britain may be an unknown crocodile or even a surviving mosasaur (Heuvelmans, 1986). During a Japanese expedition to this lake in 1994, with Dr. Roy P. Mackal as scientific advisor, a

migo

was filmed, leading Mackal to speculate that it may be a surviving, evolved archaeocete. Since participating in a second expedition here, however, during which time a clearer

migo

film was obtained, Mackal is convinced that the

migo

is not a cryptid at all—nor even a single animal. Instead, it is a composite, an optical illusion actually featuring three saltwater crocodiles

Crocodylus porosus

engaged in a mating ritual, involving two males and one female (Shuker, 1998b).

At least one type of British mystery cat is mysterious no longer— the Kellas cat of northern Scotland. This predominantly black, gracile, large-fanged felid, represented by several preserved specimens dating from the 1980s onwards, has lately been shown to be an introgressive hybrid of the Scottish wildcat and domestic cat— thus confirming the present author’s predictions as to its likely taxonomie identity (Shuker, 1989,1990b, 1993b).

In addition to the various identities offered by Heuvelmans as explanations for the Nandi bear in his checklist, the present author considers that two supposedly extinct mammals—the short-faced hyaena

Hyaena brevirostris

and a species of chalicothere—may also be involved (Shuker, 1995f). A chalicothere identity for this cryptid is supported by Brown University ungulate expert Prof. Christine Janis too (Janis 1987).

Heuvelmans’s list offered a surviving deinothere as a putative identity for the Congolese water elephant (Heuvelmans, 1986). As noted by the present author, however, the latter cryptid shares little similarity with deinotheres, but it does greatly resemble the predicted appearance of a large yet otherwise little-changed, modern-day descendant of early proboscideans, such as

Phiomia

and

Moeritherium

(Shuker, 1995f).

Janis has suggested that the mysterious southern Ethiopian “deer” listed by Heuvelmans is much more likely to be a surviving Ethiopian subspecies of the fallow deer

Dama dama

than a persisting representative of the antlered, outwardly deer-like giraffe

Climacoceras

as proposed by Heuvelmans, who erroneously referred to

Climacoceras

as a deer (Heuvelmans, 1986; Janis, 1987).

Researchers conducting biochemical and genetic tests upon tissue samples obtained from the carcass of the Rodriguez onza—the only onza specimen made available for full scientific examination—have so far been unable to differentiate it from pumas. They have therefore opined that this supposed onza is indeed merely a puma (Dratch, et al., 1996). This identity had already been predicted for it by the present author, who considers that onzas may well prove to be a gracile mutant form of the puma, rather than comprising either a distinct puma subspecies or an entirely separate species (Shuker, 1998c, 2002b).

The Brazilian

mapinguary

was listed by Heuvelmans as an unknown primate. However, Goeldi Museum zoologist Dr. David Oren has been conducting field researches in the dense Mato Grosso region of Amazonia concerning this cryptid for several years, and considers that it is much more likely to be a surviving mylodontid ground sloth. He has revealed that this region’s Indians claim the

mapinguary

has red fur, is as tall as a man when squatting on its hind legs, leaves strange footprints that seem to be back-to-front and horse-like fecal droppings, emits loud shouting cries, and is said to be invulnerable to bullets. Although mylodontids officially died out a few millennia ago, they are known to science not only from fossils and preserved fecal droppings (which are indeed horse-like), but also from some remarkable mummified specimens, still covered with reddish-brown fur. These have revealed that mylodontids had bony nodules in their skin that would have acted as an effective body armor — thus explaining the

mapinguary’s

invulnerability? (Oren, 1993; Shuker, 1995f).

In his original checklist, Heuvelmans commented that the outsized “rabbits” reported from central Australia may be giant kangaroos belonging to the fossil genus

Palorchestes

(Heuvelmans, 1986). However, as pointed out by Janis, it is now known that

Palorchestes

was not a giant kangaroo, but a genus of diprotodont. Consequently, Janis considers that a much more likely identity for Australia’s giant “rabbits” is a surviving species of sthenurine kangaroo. Nevertheless, she does favor a modern-day species of

Palorchestes

(rather than

Diprotodon

, as suggested by Heuvelmans) as a plausible identity for the superficially tapir-like

gazeka

(more commonly termed the devil pig) of Papua New Guinea (Janis, 1987). These amendments were incorporated in Heuvelmans’s updated checklist (Heuvelmans, 1996).

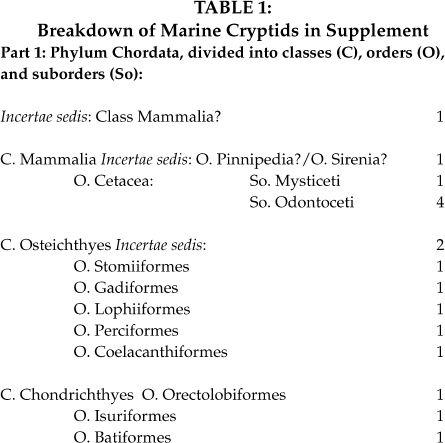

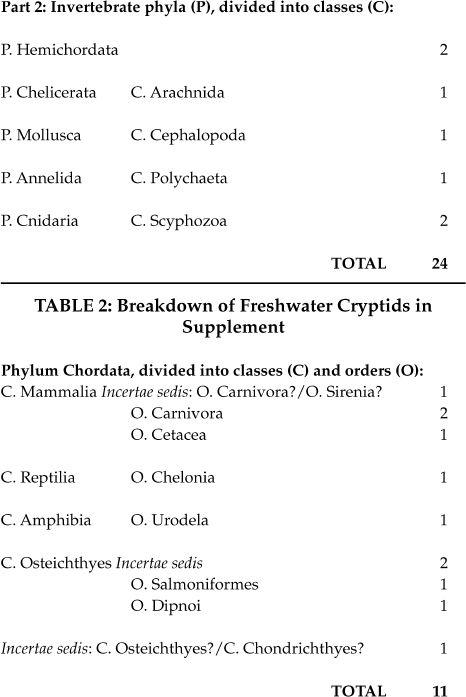

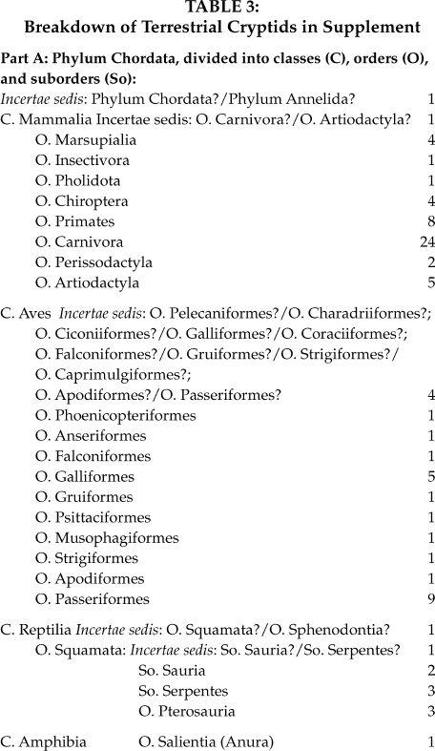

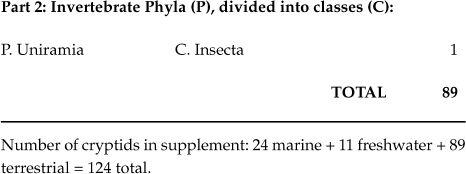

In his checklist, Heuvelmans included three tables, which classified and numbered the marine, freshwater, and terrestrial cryptids listed by him. The total number of cryptids in each category was as follows. Marine: 21-24; freshwater: 19-28; and terrestrial: 70-85. The reason why the totals were not precise is because in some cases Heuvelmans offered more than one identity for a given cryptid, and some cryptids listed by him may be composites, i.e. comprising more than one species erroneously lumped together as one by eyewitnesses.

I have provided three corresponding tables classifying and totaling the marine, freshwater, and terrestrial cryptids listed in this supplement. The totals given in these tables are precise. This is because I have only taken into account the most likely identity for each cryptid (incidentally, alternative identities noted in the addendum have not been included in the tables, as these refer to cryptids in Heuvelmans’s list, not to those in this supplement), and also because there do not appear to be any “composite identity” examples present among the cryptids listed here.

As for the tables’ taxonomie content: I have categorized cryptids down to the level of order within the phylum Chordata, and down to the level of class within all other (i.e. invertebrate) phyla, as I feel that to attempt anything more precise than this here would unavoidably introduce an unwieldy and unnecessary extent of taxonomie nomenclature in what is primarily a documentation of cryptids, not an exercise in defining or elucidating zoological taxonomy. For this same reason, I have chosen to ignore the wrath of taxonomy purists by adhering to familiar, traditional systems of classification—rather than complicating matters needlessly by introducing new (and often still controversial) versions that have yet to gain widespread recognition beyond their immediate circle of proponents and which would thus require extensive explanation in order to be readily comprehended here (a case in point is the radically revised classification system for birds inspired by molecular evidence).

As demonstrated by this supplement, diligent bibliographical and field research can and will surely continue to yield reports of hithertounpublicized cryptids worthy of addition to Heuvelmans’s original checklist—and, in turn, necessitate the preparation of further supplements. This research, therefore, should certainly be encouraged.

Having said that, however, I hope that publications such as the account presented here will ultimately lead not to an ever-increasing, but rather to an ever-decreasing, number of cryptids so listed — by actively stimulating investigations that climax in the formal discovery and scientific description of cryptids in Heuvelmans’s list, in this current supplement, and in any future supplements. For this would finally bring to an end these animals’ unjust, protracted exile from scientific respectability, and provide them with the coveted honor of official scientific recognition that they have so greatly, and for so very long, deserved.