THE BEAST OF BOGGY CREEK: The True Story of the Fouke Monster (13 page)

Read THE BEAST OF BOGGY CREEK: The True Story of the Fouke Monster Online

Authors: Lyle Blackburn

In fact, as I have learned through my research, Charles Pierce was a very talented guy, not just in films, but in graphic design, illustration, news casting, writing, acting, singing… you name it. He was a virtual renaissance man who defined the DIY (do-it-yourself) attitude of an industrious artist. This kind of thing might be common now with the hordes of indie filmmakers shooting in their backyards direct to DVD, but back in the day, Pierce was a pioneer.

Pierce passed away in March of 2010, but I had the pleasure of speaking to his daughter, Amanda Pierce Squitiero, about the man and his legend. She was no stranger to his movie sets and even appears as a small girl in the climax of

The Legend of Boggy Creek

. It was surreal telling her how her father’s movie had influenced my own family back in the 1970s. After seeing the movie, I can remember countless times when my dad would growl and jump out of the shadows to scare us. My mom and sister would scream “the Boggy Creek monster!” while I laughed.

But for Amanda it was much more emotional. She recalls being frightened nearly to death as she was shooting the scene in the movie. The fear she had on screen was real that night, back in 1971, in that old frame house out in Fouke. When she spoke to me about her father, her emotional ties to him were evident, along with the respect she has for his accomplishments, not just with

The Legend of Boggy Creek

, but throughout his life.

Charles Bryant Pierce grew up in Hampton, Arkansas. From a very early age he was involved with film. As a kid, he and his lifelong friend, Harry Thomason, who would go on to create popular television shows such as

Designing Women

and

Evening Shade

, used an old 8mm camera to make their movies. It must have been here that the cinematic seed was planted, although as a young man he set his sights on a career in graphic design. By his mid-twenties, he was working as the art director for KTAL-TV in Shreveport, Louisiana, but his do-it-all spirit would eventually land him in other positions, including weatherman and host of a children’s cartoon program for the station.

In 1969, Pierce moved to Texarkana where he opened a small advertising agency, while at the same time, played a character called Mayor Chuckles on a local television show. Although he was popular in his role as Mayor Chuckles, it was the advertising work that gave him the opportunity to use all of his combined talents, and thus set the stage for his imminent jump to filmmaking. Using a basic 16mm handheld camera, he began producing commercials for local businesses, one of which was Ledwell & Son Enterprises, a builder of 18-wheel trailers and other farming equipment. Ledwell commissioned a series of commercials that gave Pierce the opportunity to film heavy trucks on the highways and other machinery in the fields. This was an important step, since it was Ledwell who would later put up the money to film

The Legend of Boggy Creek

.

Like all the residents of Texarkana in the early 1970s, Pierce had been following the sensational newspaper reports describing a hairy, ape-like creature which haunted the creeks near Fouke. As a result of his interest in the stories, he conceived an idea for doing a regional film based on the phenomenon. Seeing an opportunity to capitalize on the frenzy, he approached his wealthy client, Mr. Ledwell, and presented the idea. But Ledwell did not respond with much confidence in Pierce’s ability to make a film. He was also doubtful of the subject matter. In a 1997 interview with the popular horror magazine,

Fangoria

, Pierce recounted his first proposal to Ledwell. When asked what kind of movie he wanted to make, Pierce told Ledwell: “I want to do one about that booger that’s jumpin’ on folks down the road there. It was in the papers every morning, you know, about the Fouke Monster and how it’d jumped on somebody else.”

When asked at the time if he believed in the monster, Pierce simply replied, “I don’t know if I believe it or not—but it sure will make a good movie!” Ledwell finally agreed and signed on to back Pierce.

With Ledwell on board, Pierce then needed to enlist the cooperation of the Fouke residents. This would prove to be even more difficult than convincing the stodgy old business man to bankroll a Bigfoot movie. When Pierce made his first scouting mission down to Fouke, he asked some of the locals what they thought of the idea. On the whole, the folks of the little town did not take kindly to the notion. Pierce remembers: “They didn’t want to make a movie. They didn’t ask for money. They didn’t want anything. They wanted to be left alone, in fact.”

That would later become a huge problem for Pierce, but it did not deter him one bit. The story was too good, and if the people of Fouke did not want to help propel their namesake monster to the big screen, then Pierce would have to work around that. And he did.

Pierce continued to interview locals until he found some who didn’t mind sharing their stories or helping out with the film. One man offered to take Pierce down to his barn where he told of a startling encounter with the beast. The man had apparently surprised it one morning as he stepped outside to start his daily chores. He had a long look at the thing as it headed back out across a pasture toward the cover of the trees. Like other witnesses, he described it as a hairy, man-like creature that walked upright on two legs. Pierce was enthralled with the story and wanted to include the scene in his movie, but the witness wanted no part of the film, whether reenacting the encounter or simply mentioning his name. Pierce agreed to the anonymity, knowing that it wouldn’t matter whether it was the actual storyteller or someone else who re-enacted the scene in the movie.

After more research and story-gathering, Pierce felt he had enough compelling source material to move to the next step, which was to find a competent writer to pen the screenplay. For the job, he hired an advertising associate by the name of Earl E. Smith, who also lived in Texarkana. Smith had never written a movie script, but like Pierce, he would prove to be just the right man for the job.

Using the working title “Tracking the Fouke Monster,” Pierce went ahead with filming despite the fact that a script had yet to be drafted. Since they planned to use a documentary-style approach with narration overdubs, it would not require much in the way of rehearsed dialog, which was perfect since he had no real actors on board to even deliver the lines. Instead, he planned to film actual Fouke residents as they acted out the monster encounters, which had appeared in the news or he had learned about through personal interviews. One such local was Smokey Crabtree, whose son (Lynn) had come face-to-face with the monster six years earlier. While seeking information about that encounter, Pierce and Smith also talked Smokey into acting as sort of a tour guide around town and in the swamps. This was a fortunate move, as Smokey’s lifelong experience in the bottoms proved to be invaluable when it came to accessing the remote regions for filming.

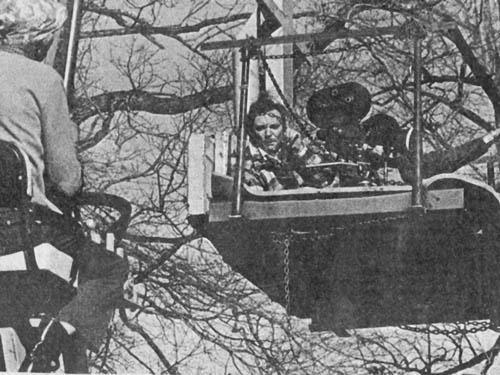

Pierce signals the crane operator to raise the camera platform while filming a high angle shot. (Courtesy of the Texarkana Gazette)

In exchange for a nominal fee, Smokey agreed to guide Pierce through the waterways of Mercer Bayou so that he could shoot the scenery. Each morning, Smokey would launch his handmade canoe into the bayou, rowing Pierce around until the director got the shots he needed. Pierce also shot footage of Travis, Smokey’s other son, who stood in for Lynn since he did not want to participate in the movie.

In some cases, Smokey also acted as an informal liaison between the movie makers and the townsfolk, convincing locals to participate in the movie, especially those who claimed to have seen the monster and had firsthand stories to tell. Pierce also resorted to some crafty low-budget ingenuity to cast the rest of the parts: he simply hung out at a local gas station and waited for people to drop by. When he spotted someone that fit the description of a person he needed, he would ask them if they wanted to be in a movie. Pierce described the process in the interview with

Fangoria

:

When someone pulled in, we’d say, ‘Now she’d be a good Peggy Sue.’ And we’d walk out there to the gas pumps and say, ‘Ma’am, we’re shootin’ a little movie. Would you like to be in it?’

She’d say, ‘Well, what do I have to do?’ And I’d say, ‘Oh, you just run across this field out here.’ We’d get out there in the field and she’d say, ‘What do I do?’ and I’d say, ‘I want you to come across over there screamin’, and run real fast. We never did makeup or any of that, unless the creature got on ‘em and then we’d put on a little ketchup for blood.

Eventually Pierce had enough Fouke residents on board to make a go at it. Some were even eager to participate in the film. The chance to potentially see themselves on the big screen compelled them to show up and try their hand at acting. Even the local police force assisted Pierce by setting up roadblocks and supplying props such as vehicles.

For a crew, Pierce relied on volunteers. He already had a small roster of high school age kids from Texarkana who had helped him shoot commercials, so he called on their help down in Fouke as well. Pierce rounded out his crew with some of the local Fouke kids and other volunteers. Since the kids often had school or chore obligations, they were not always available every day. Having a large pool of volunteers ensured that he would have enough help during the shoots, although the ever-changing makeup of the crew did not make things easy.

In the role of the monster, Pierce used a few different actors, including his brother-in-law, Steve Lyons; Steve Ledwell; and local boy, Keith Crabtree, who ultimately received the credit in the film. To create the costume, Pierce used a bit of ingenuity to fashion something that would reflect what people claimed to have seen and would also hopefully frighten audiences in the climatic final scene.

Once we got to the ending, I knew we had to do something for some kind of payoff. So we ordered a gorilla suit from some costume house in Los Angeles, and I went down to the five-and-dime store and bought a bunch of old wigs, and we cut ‘em into pieces and sewed ‘em all over the top of the gorilla’s head, and that was it.

Today, many small-time movie makers are familiar with the methods Pierce used to make

The Legend of Boggy Creek

—“guerilla film making,” as it has come to be known—but at the time Pierce was definitely taking a huge risk by investing time and other people’s money into an independent venture that literally depended on the effectiveness of a modified gorilla mask and unproven actors. However, as time would tell, the movie would ultimately make a monkey’s uncle out of any doubters.

The Legend of Boggy Creek

If you’re ever driving down in our country along about sundown, keep an eye on the dark woods as you cross the Sulphur River Bottoms. You may catch a glimpse of a huge, hairy creature watching you from the shadows.— From the narration of

The Legend of Boggy Creek

Not only has

The Legend of Boggy Creek

become a B-movie cult classic, but it also has bragging rights for being one of the first horror films shot docu-drama style. Whether intentional or not, the film’s gritty, piecemeal production and first-person accounts impart a sense of realism that makes the incredible story seem all the more believable. This technique, common today, was way ahead of its time and is a major reason why this cult gem endures despite its shortcomings.

Of the 60 or so “actors” eventually credited in the film, nearly all of them ended up being locals who played themselves, or stood in for other locals, to reconstruct the alleged encounters with the monster. Much of the film’s soundtrack was overdubbed using a combination of suspenseful narration and eyewitness retellings (voiced in unabashed Southern drawl), which contributes to the overall feeling of authenticity. These people look and sound scared, as if Pierce had miraculously been there to film the encounter as it was actually happening. Because of this, it seems less like a movie and more like a horrifying live news broadcast. Not surprisingly, it was frightening to many viewers, especially during its original release in 1972. The movie scored a G rating, which drew in the younger audience, but the movie managed to spook the adults as well.