The Battle of White Sulphur Springs (2 page)

Read The Battle of White Sulphur Springs Online

Authors: Eric J. Wittenberg

The secession crisis of 1861 hit the Commonwealth of Virginia harder than most states. Virginia did not secede during the original wave of secessions after the election of President Abraham Lincoln, as the state's population was deeply divided on the question. It did not pass an ordinance of secession until after Lincoln called for volunteers to put down the rebellion following the surrender of Fort Sumter.

Not all Virginians supported secession. A referendum on secession was held on May 23, 1861. Twenty-five counties in the northwestern section of Virginia opposed secession and delivered majorities for the Union. A two-week-long convention met in Wheeling on June 11, 1861. The delegates represented thirty-eight counties, five of which were east of the Allegheny Mountains. The purpose of the convention was to discuss splitting northwestern Virginia from the rest of the commonwealth to form a new state that would remain loyal to the Union. The convention adopted an ordinance for reorganization of the state government on June 19 and then undertook the task of developing a government and infrastructure for the new state.

1

In the fall of 1861, the voters of “Restored” Virginia approved the severing of thirty-nine counties from the rest of Virginia. The vote was nearly unanimous. The process of creating a new state began almost immediately. It took time to define the precise boundaries of the new state, and a constitution had to be drafted. The legislature of the “Restored Government” of Virginia had to approve the severance of the new state, which occurred on May 13, 1862. The act included forty-eight counties of “the old Commonwealth.”

Once the Restored Government's legislature approved the split, the United States Congress had to approve the admission of the new state to the Union. On May 29, 1862, Senator Waitman T. Willey, from Morgantown, submitted a petition for the admission of West Virginia in the U.S. Senate. The original version of the bill called for the addition of more counties to the new state and the gradual emancipation of slaves, but Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts offered an amendment requiring immediate emancipation. When that amendment failed, Willey offered a substitute amendment that called for the admission of West Virginia as a state as soon as the constitutional convention reconvened and accepted a proposal that all slave children born after July 4, 1863, would be freed.

2

This amendment also failed, leading to more political wrangling over the question of the emancipation of the slaves. Fortunately, a compromise was finally reached. Known as the Willey Amendment for its sponsor, Senator Willey, it provided that all slaves under the age of twenty-one on July 4, 1863, would be freed upon reaching that age.

3

The Willey Amendment passed, and on July 14, 1862, the statehood bill was enacted.

4

When the statehood legislation was brought to Lincoln for signature, the president was “distressed by its passage” and asked the members of his cabinet for written opinions regarding the constitutionality of the act, as well as the political expediency of admitting West Virginia to the Union. The six sitting cabinet officers split on the question, and Lincoln agonized over whether admitting a new state to the Union under the circumstances would be unconstitutional. He finally signed the bill on December 31, 1862, believing the admission of the thirty-fifth state to be “expedient.”

5

A condition of admitting West Virginia to the Union was the redrafting of the new state's constitution to include the emancipation provisions, which took time to convene and approve. The new constitution then had to be submitted for approval by the voters of the new state, who approved it. The results were certified to President Lincoln, who issued a proclamation that sixty days from the date of issueâApril 20, 1863âWest Virginia would become a state.

6

The birth of the new state did not go smoothly. In the spring of 1863, determined to break up the critical supply line of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, General Robert E. Lee authorized a raid by the cavalry brigades of Brigadier General William E. “Grumble” Jones and Brigadier General John D. Imboden, the stated purpose of which was the destruction of the B&O at certain critical points, the defeat of Union troops in the area and the gathering of supplies and manpower for the Confederate armies. The month-long raid penetrated deep into West Virginia but failed to prevent the birth of the new state.

7

After electing statewide officials, West Virginia formally became the Union's thirty-fifth state on June 20, 1863. The new state lacked any infrastructure and, based on the commonwealth of Virginia's institutions and laws, created its own executive branch and cabinet offices, a bicameral legislature and its own judicial system, much of which had to be created from scratch.

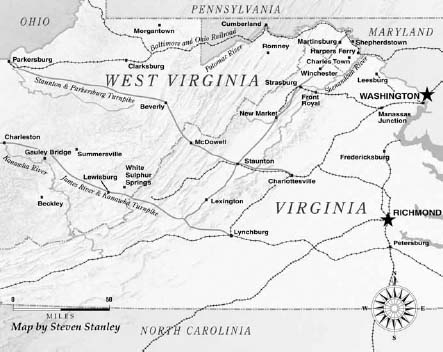

West Virginia was a battleground right from the outset of the war. From the start, the Union controlled two of the four main transportation corridors through that portion of northwestern Virginia that became the state of West Virginia. The Federals controlled the Ohio River on the west and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad on the north. The Confederates controlled the corridor to the east, beginning at a point between Winchester and Martinsburg to the north and Covington to the south. This critical corridor included the Virginia Central Railroad (connecting Richmond and Covington, about twenty miles east of White Sulphur Springs) and the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad, which connected Richmond and Lynchburg to east Tennessee. The Kanawha and James River corridor was the central point of this grid, and it proved to be the most fought-over portion of the new state. The Union controlled the Kanawha River Valley, while the Confederates controlled the Greenbrier and Jackson River watersheds, with a mountainous no-man's land in between, leading to a protracted stalemate. Both sides tried to break this stalemate multiple times, with poor results for both.

8

West Virginia's loyalties remained divided for the duration of the war.

The White Hotel, Greenbrier Resort, as it appeared in 1857.

West Virginia State Archives

.

Greenbrier County rests in the southeastern portion of West Virginia, and its eastern county line also serves as the dividing line between Virginia and West Virginia. One of the world's most famous resorts, the Greenbrier, long known for the curative powers of its waters, is situated in the town of White Sulphur Springs, which is just a mile or two west of the state line. Greenbrier County held strong Confederate sympathies. It cast no votes for Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election. It sent no delegates to either Wheeling Convention. “Once the die [of secession] had been cast, Greenbrier County generally gave its loyalty to Virginia and the Confederacy as unreservedly as it had once extended its devotion to the Union,” noted historian Otis K. Rice.

9

Theater of operations.

The 1860 census indicated that there were 2,474 white male residents between the ages of eighteen and fifty-five residing in Greenbrier County. Of that number, about 2,000 served in the Confederate forces, while other men younger than eighteen and older than fifty-five from Greenbrier County enlisted in the Confederate service.

10

Greenbrier County had already served as a battleground more than once during the first two years of the Civil War. Union and Confederate forces clashed at Lewisburg, which was the county seat, in the spring of 1862, and the county changed hands several times during the early years of the conflict.

11

Lewisburg is an old town and has served as the county seat since 1778.

12

While Greenbrier County was still a part of the commonwealth of Virginia, the state Supreme Court occasionally held sessions in Lewisburg, meaning that the court had to maintain a full law library at the county courthouse. The new government of West Virginia needed that full law library to help develop the judicial system for the nascent state.

13

Suddenly, quiet Lewisburg was about to become the eye of a gathering storm as Union and Confederate forces zeroed in on that law library. The hard hand of war was about to visit Greenbrier County again.

1

William Woods Averell and His Raiders

Brigadier General William Woods Averell was born in Cameron, New York, on November 5, 1832. He came from hardy stockâhis father had been one of the first settlers of the area; his paternal grandfather, Ebenezer, was a Revolutionary War soldier; and his other great-grandfather, Solomon, was one of the early settlers of Connecticut.

14

His great-grandfather, Josiah Bartlett, was the first constitutional governor of New Hampshire and signed the Declaration of Independence.

15

Young William spent his youth in school and working as a drugstore clerk. He received an appointment to West Point in 1851, graduating in the bottom third of the class of 1855. Averell's superb skills as a horseman made him a natural for the cavalry. He was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Regiment of Mounted Rifles, later redesignated as the 3

rd

U.S. Cavalry. While at the military academy, Averell befriended cadet Fitzhugh Lee of Virginia, who was a nephew of the academy's superintendent, Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee. Fitz Lee also wanted to serve in the cavalry, and the two grew as close as brothers, even though they were a year apart at the academy.

16

Not long after being commissioned, Averell attended the Cavalry School at the Carlisle Barracks and spent a tour of duty as the adjutant to the commanding officer. In 1857, he transferred to a post in New Mexico, where he fought Indians and received a serious leg wound that nearly forced him to leave the service. He spent nearly two years hobbling around on crutches while on recuperative leave. Averell went to Washington with the coming of war in April 1861, seeking to return to duty. After a stint as a staff officer that placed him on the battlefield at First Bull Run in July 1861, Averell became colonel of the 3

rd

Pennsylvania Cavalry.

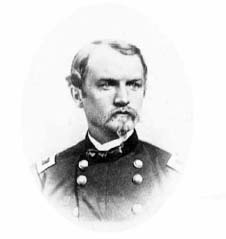

Brigadier General William Woods Averell, commander of the Fourth Separate Brigade, in a previously unpublished image taken when he was colonel of the 3

rd

Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Brian Stuart Kesterson

.

Although an ambitious man, Averell was a conservative commander. He believed that troops needed constant training and did not want to take them into the field if he did not believe them to be ready. As a result of his efforts, the 3

rd

Pennsylvania soon gained the reputation of being one of the best-trained and best-disciplined volunteer cavalry regiments assigned to the Army of the Potomac. “He was an excellent drillmaster, with proper views of what constituted proper discipline,” recalled an admiring trooper. “Instruction in a systematic manner, with a view of preparing these men for the service expected of them, was commenced and persistently followed in the most industrious and painstaking manner.”

17

Under McClellan's leadership, Averell commanded a brigade of cavalry during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, taking part in the operations at Yorktown, Williamsburg, Fair Oaks and Malvern Hill, and routed the Rebel cavalry in a skirmish at Sycamore Church on August 2, 1862. He fell victim to the so-called Chickahominy fever, a nasty and persistent malarial fever, in the aftermath of the Peninsula Campaign, requiring five weeks of recuperation. A relapse of the fever forced him to miss the Second Bull Run and Antietam Campaigns in the summer of 1862. When he returned to duty, he was promoted to brigadier general and assumed command of a division later that fall.

18

When the Army of the Potomac finally crossed the Potomac River into the Loudoun Valley of Virginia, his division engaged in frequent skirmishing and, when the army advanced, was hotly engaged along the passes of the Blue Ridge.

19