The Battle for Gotham (45 page)

Read The Battle for Gotham Online

Authors: Roberta Brandes Gratz

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century

Van Arsdale was speaking in favor of the expressway, and I said to him, “What about the jobs of all those people that are going to be wiped out by the expressway?” And a lot of those people are blacks and Puerto Ricans who have a very hard time getting work. And he said, “Oh, I can’t be concerned about those jobs.” And he wasn’t. He was concerned with construction only. High-paid construction workers, temporary jobs. To this day, that’s the basis on which jobs are talked about for Westway.

This is still true in debates on highways, stadiums, casinos, malls, and similar big projects.

In reality, highways and transit are both job creators, at least for jobs that last the duration of the construction project. The same energy and advocacy never seem to get behind the kind of entrepreneurial investment that creates long-term jobs not in construction.

An important distinction exists, however, in the jobs created by highways and transit. Most of the highway jobs are on-site, with cement, steel, and other supplies coming from distant places. With transit, more meaningful jobs and more of them can be created off-site but within the state.

In 2005 the MTA distributed an eight-page brochure highlighting dozens of subway, bus, and commuter rail parts that are made around New York State. A map of the state showed forty-four locations of parts subcontractors for subway, bus, and railcars. Diagrams of the hybrid buses, subway, and railcars identified the location at which each component is produced. The minimum number of scattered manufacturing sites was ten for hybrid buses produced in Oriskany in central New York; the maximum was twenty-eight for the Kawasaki railcars produced in Yonkers, a city north of New York City. “The economy of the southern tier of the state is very dependent on this work, especially the rebuilding of subway cars,” Downey points out. The shells of 660 new subway cars were delivered by ship from Brazil to the Port of Albany, for example, and trucked to an assembly plant with eleven hundred employees in Hornell, in the southwest corner of the state. The Hornell plant is producing the propulsion and gear units. All the parts work, Downey adds, is highly labor intensive. The lighting for new cars comes from Buffalo, the ventilation system from Auburn, and fabricated metal parts from Kingston and Farmingdale. The propulsion system for the new clean-fuel city buses comes from Johnson City and the sheet metal from Utica.

BEYOND TRANSIT: REGENERATION OR REPLACEMENT?

It would be a mistake, however, to evaluate the Westway defeat

only

on the basis of the enormous transit benefit from the trade-in funds. Multiple positive ripple effects are equally significant:

• The Westway corridor from the Battery to Forty-second Street along the Hudson River has been transformed on both sides of the roadway.

• Neighborhoods around the city experienced tremendous infusions of new residents, lured, in part, by vastly improved transit service.

• A stronger awareness of and interest in the full 575 miles of New York City waterfront evolved or were accelerated after the intense focus on this 5-mile section.

• The regional transit network shared in the new system investments, improving access to the city for local users, commuters, and visitors.

9.2 One of those lovely moments with Jane, a martini break in a conversation.

Stephen A. Goldsmith

.

The benefits are not obvious, until one appreciates the critical and beneficial role of transit to urban life and the destructive role of highways. Few New Yorkers living in neighborhoods revitalized in recent decades connect the improved transit benefits they enjoy today to the defeat of Westway. “The Westway trade-in and subway investment made all the difference in my life,” reports a longtime resident of Brooklyn’s Park Slope. “Before that, you could never count on getting back and forth to Manhattan to make a business meeting on time. You never knew whether your kid’s lateness from school was something to worry about. And, you wound up spending a fortune on cabs at night (if you could get them to take you across the bridge), because you never wanted to trust the subway after dark. I’d say the subway improvements maybe doubled the value of my house.”

The transformation of the far West Side of Manhattan below Forty-second Street is probably the most visible testimony to the post-Westway change. What Jane said would happen if Westway was killed has, indeed, happened. “There is so much there,” she said of the so-called decrepit area. “Plenty of room exists for fill-in development between buildings and on empty lots. Much of that vacant space certainly ought to be developed before you add new landfill at enormous expense, if that’s ever necessary. And the new land wouldn’t be a success until these fill-ins were done in any case.”

During the Westway debate, proponents vigorously argued that the highway and landfill development were absolutely necessary to spur the revival of this stretch of the West Side. Without Westway, the area was doomed, the experts said. They were wrong. This area was certainly “ramshackle.” The condition was not debatable; the cause of the condition was. And Westway as the cure was a joke. As Jane said: “What a ridiculous idea that you put in a billion-dollar highway to manicure a place!”

ORGANIC REGENERATION GETS A CHANCE

Anyone who has observed the organic regeneration of urban districts understood how erroneous this notion was. Grand plans, for highways, urban renewal, stadia, and the like, work as impediments to authentic regeneration, and their defeat makes regeneration possible. Regeneration after defeat is not guaranteed; other conditions are necessary.

In the 1970s many properties along the route were turned into sleazy bars and illicit sex spots, supporting the image of extreme deterioration. Owners waited for the big payoff that would come with condemnation. The bars served as a useful, very visual prop for Westway advocates. Mysteriously, all of these places disappeared after Westway’s demise.

Something was ready and waiting to happen there, and it did—after Westway’s defeat. Now, property along the West Village, Gansvoort Market, and the Chelsea waterfront is among the highest-valued real estate in Manhattan. “The neighborhood is now part of the richest ZIP code in New York City and the 12th richest ZIP code in the country, according to a study by Forbes,” the

New York Sun

reported on August 14, 2006.

Many buildings have been renovated, and numerous trendy restaurants and shops opened and new buildings have been built. Too many architecturally distinctive buildings, however, were torn down, viable businesses lost, and residents displaced while the death threat hung over the area and the Landmarks Preservation Commission delayed expansion of the Greenwich Village Historic District. An expansion was passed in May 2006. A small additional district was designated—the omitted remnants of the rich district that existed when the original Greenwich Village Historic District was designated in 1966. But even this time, certain landmark-quality buildings were omitted, enabling developers to replace them with high-rise condos.

Old industrial buildings have been converted to residential lofts in the pattern established in SoHo after the demise of the Lower Manhattan Expressway plan.

6

And although residents complain that the new high-rises are intrusive and out of character, the scale of some of the new buildings—notably the three best known, designed by architect Richard Meier—are only twelve stories. This is modest for the city, especially in contrast to the excessive scale—forty stories plus—permitted in a 2005 zoning change for the industrial neighborhood of Greenpoint-Williamsburg in Brooklyn.

If Westway had been built and the new land created for development, can one imagine zoning for fewer than forty stories, and probably more with incentives? Would a wall of high-rises on a hundred acres at the river be better than what is emerging now? Most people complain about the scale of the apartment towers Donald Trump built along the river between Sixty-fifth and Seventy-second Streets, and they are lower than forty stories. Would the West Side have received zoning less than Greenpoint-Williamsburg’s forty stories plus?

THE NEW PARK—BIG IS BIG

The creation of the Hudson River Park along the waterfront puts the lie to the oft-repeated ridiculous belief that nothing big can get done in New York City. Even the

New York Times

, long an ardent advocate of Westway, noted that “this modest park is as big an urban planning success story as anything that has taken place in New York City in 100 years.”

7

Modest it may be, but it is still the largest Manhattan park built in more than a century.

Not only is this already a huge accomplishment on its own terms—about three-quarters completed—but it is the largest physical change in the city’s waterfront land use since the days when cruise ships and commerce filled a rich assortment of finger piers. The opening of the first segment in Greenwich Village in 2003 marked the beginning of serious city and state efforts to transform for recreational use waterfront areas in neighborhoods throughout the city. New segments seem to open annually.

The first segment—a ten-acre swath in Greenwich Village—included three piers extending a thousand feet offshore with lawns, playing fields, playgrounds, a children’s ecology stream, and a display garden, not to mention the spectacular views of the city’s skyline from the end of the piers. Users disagree as to how difficult it is to cross the highway. Either way, millions are indeed crossing. Any weekend, people are coming from all parts of the city. Diehard Westway proponents argue that with the highway underground, access to the waterfront would have been better. But there still would be a road to cross, an access road, not much narrower than the present highway.

Only six years since that 2003 opening, one marvels at how much more of the five-mile park already exists, with more constantly under construction. Within some common design elements, like railings, lighting, and comfortable benches, the diversity of uses and potential experiences is remarkable. Boating options range from sailing and kayaking to touring, with more boating opportunities planned. Lawns for picnicking, sun-bathing, or socializing are plentiful. Playgrounds, tennis courts, a fabulous historic barge, and more are found along the way. Even a small, protected wildlife sanctuary for migrating birds exists with a variety of plantings and flowers to attract whatever Mother Nature brings.

Protecting the fish was at the heart of the Westway battle, and the new park seems to do this well with a generous assortment of habitat preserves. The areas between the piers are off-limits to filling and platforming and continue to function as they have for years. The piers and pilings slow the river flow and create calmer areas, providing shelter for the fish. Decking has been removed from what used to be piers, creating a series of protected pier ruins—pile fields that are both fish habitat and sculptural reminders of the waterfront’s history when piers lined the water’s edge, one after another. Their function as habitat is preserved; if more than 30 percent of the pilings in one field is lost, replacement is required. What is sadly missing, however, is any kind of interpretive signage to remind the visitor of some historic events and activity. This waterfront was the incubator of the city’s and, in effect, nation’s economy in the 1800s. Not a clue is offered.

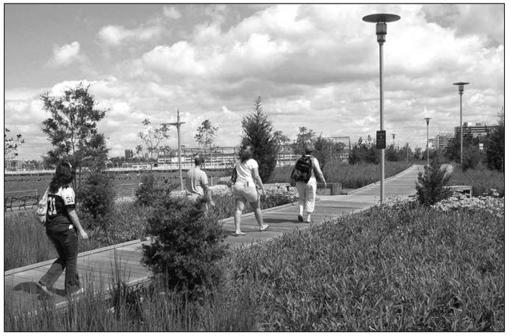

9.3 The Tribecca boardwalk section of Hudson River Park.

Albert Butzel

.

Nevertheless, born out of the Westway defeat, this is the greatest park development since Central Park and not just because it is the largest park added to the city since then. It is a balanced blend of new park space, recreational uses, city service structures, and nearby new development. The design evolved out of a three-year planning process with definite input from the assorted adjacent neighborhoods. Because the end result reflects that input, Hudson River Park feels more like a string of contiguous but varying parks, some more passive or active than others.