The Ball (6 page)

Authors: John Fox

“We go around to the schools now to educate the next generation about the tradition,” said Graeme. “Kids naturally want to be on the winning side. But we explain that's not how it works. We'll meet a lad who lives in Uppie territory who's sure he's Uppie, but we'll ask a few questions and find out, âOh, you had a granddad who won a ba' for the Doonies, did you? Well you're a Doonie then.' ” Graeme and his mates were, in other words, in full recruitment mode.

Graeme ducked out of the room and returned with a shining black and brown sphere, which he ceremoniously placed in my hands. “There she is. The sacred orb herself.”

Expecting to see some roughly stuffed and stitched facsimile of a ball, I gasped aloud at the obvious craftsmanship of what I held. Approximately the same size as a soccer ball but three times as heavy, the ba' is lovingly handstitched with eight-cord flax from top-quality leather donated by a German shoe company. Assembled with eight panels, painted alternately black or brown, and coated with a heavy shellac, the ba' is crafted not only to survive the punishing pressure of the pack on game day but to live on as the most cherished trophy of the man fortunate enough to take it home. At that moment, I wished Aidan could be there to hold that ball and feel with his own hands the care and artisanry that went into it. It was a thing of beauty.

George, a stocky, bearded 62-year-old whose day job is on a North Sea oil rig, estimates he's made close to 50 such balls over a 27-year span. Each ba' takes maybe 40 hours to produce. The stitching alone can take two days. The core is formed from crushed cork that came originally from the packing material in old fruit barrels and today is imported from Portugal.

“Ach, the stuffing is merciless work,” he said, looking at his callused hands. “You leave a wee hole in one of the seams and keep packin' doon and doon and doon.”

Rumors and accusations still fly that a Doonie ba' maker will slip a bit of seaweed in the ball or an Uppie a bit of brick from the wall to draw it magically back to its source. When asked if he'd ever attempted such sorcery himself, George pleaded the fifth. “Well, now I've heard the same stories . . .”

With a look of impatience, as though my fascination with the ball itself might distract me from the game's deeper meaning, Davie Johnston, a successful businessman in his late 50s who moved away from Orkney when he was 19 but has returned every year since to play the ba', leaned in to me and rested his hand solemnly on the ball.

“This isn't a trophy. This is heritage. This is history. This is tradition. This is what I won and my granddad and his granddad won before me and that's what it's about. It goes back that far and that deep. It's hard to understand the depth of feeling we have for it. It's huge.”

D

espite some recent efforts to trace the murky origins of football to the Chinese kick ball game of

cuju

or to the Roman game of

harpastum

, there's no evidence that those or any other sports of the ancient world had any direct influence on the development of football as it emerged in medieval Europe.

Cuju

, a game that may date as early as the fourth century

BC

, became wildly popular in the royal courts of the Han dynasty and eventually spread to Korea and Japan. The game, which resembled modern football in some ways, was described in a poem of the time:

A round ball and a square wall,

Just like the Yin and the Yang.

Moon-shaped goals are opposite each other,

Each side has six in equal number.

The stuffed ball was eventually replaced by one with an inflated pig's bladder and goalposts replaced gaps in walls as the target. Although the game played an important role in Chinese daily life and enjoyed an impressive run of more than 1,500 years, it never appears to have spread farther than the royal courts of East Asia. And while it's quite possible that Roman soldiers brought their game of

harpastum

with them when they invaded Britain, there are no accounts of Romans mixing it up with their subjects on British pitches. As one British scholar has humbly pointed out,

harpastum

, which involved assigned positions covering zones of play, was a more sophisticated game than early English football. In fact, it would take until nearly the 19th century for football to gain the level of organization and sophistication that the Roman sportâor

cuju

, for that matterâhad achieved by the first century

AD

.

As scant as the historical record is when it comes to games and pastimes, football as it's played today can be confidently, if circuitously, traced to early medieval villages of Britain and France. One of the earliest mentions of a football-like game is from the ninth-century

Historia Brittonum

, a mythologized account of the earliest Britons. In the fifth century, according to the author, Vortigern, a Celtic king from Kent, was attempting to build a tower, but it kept mysteriously collapsing. The king's sages called upon him to sprinkle the tower's foundation with the blood of a boy born without a father, so he sent out emissaries far and wide to find such a boy. When they finally located him, he was in the middle of playing an undescribed game of ball (

pilae ludus

) with a group of boys. The fatherless child, possibly Britain's first recorded footballer, grew up to be none other than Merlin, the wizard of Arthurian legend. (Apparently, Harry Potter wasn't the first young wizard to play ball!)

Coincidentally, the first appearance of the words “ball” and “ball play” in the English language also has an Arthurian connection. Around the year 1200, an account of the festivities surrounding King Arthur's coronation describes how the guests “drove balls far over the fields,” an ambiguous reference that may or may not suggest a variation of football.

From its earliest appearance, “mob football,” as the game came to be known, was played across England and France as part of festive celebrations, particularly those connected with the feast day known as Shrovetide. Celebrated elsewhere in the Christian world as Fat Tuesday or Mardi Gras, Shrovetide was traditionally the last hurrah of partying and excess before Ash Wednesday kicked in and Lenten fasting and penance began. Originally a pagan springtime celebration, Shrovetide involved a wide range of games and festivities, like bell ringing, cockfighting, cock throwing, and ball games.

What some regard as the earliest record of a football-like game in England is a description of Shrovetide games that took place in London in 1174:

After dinner all the youth of the city proceed to a level piece of ground just outside the city for the famous game of ball. The students of every different branch of study have their own ball; and those who practice the different trades of the city have theirs too. The older men, the fathers and the men of property, come on horseback to watch the contests of their juniors . . .

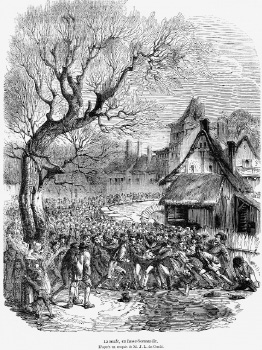

Game of

la soule

in a village in Normandy, France, 1852.

Around the same time a nearly identical game, called

la soule

, was just beginning to take off in the villages of Normandy and Brittany. Played with a ball made of leather wrapped around a pig's bladder or stuffed with hemp, bran, or wool,

la soule

pitted parishes or villages against each other. Festive games took place at Shrovetide or at Easter, Christmas, or parish patron saint days. As with other variations of mob football, there was no limit to the number of players and no rules to speak of, with play involving huge violent scrums and chaotic melées. The goal, as in the ba', was to capture the ball and force it back to their home village, submerging it in a local pond to win the game. Some games ritualistically pitted married men against single men. One game in the town of Bellou-en-Houlme was reported to include 800 players and 6,000 spectators! After the games there would be the medieval equivalent of tailgate parties, with drinking, dancing, and carousing well into the evening. The game's early popularity in France is suggested by a deed from 1147 in which a lord specifies the settlement of a debt with the delivery of “seven balls of the largest size.”

La soule

and other forms of football were played not just for the sake of recreation but as magical rites to promote fertility and prosperityâthus the deep connection with Shrovetide and the arrival of spring. In his classic study of European mythology,

The Golden Bough

, J. G. Frazer interpreted early ball games as contests in which capturing the ball would ensure a good harvest or a good fishing season. In some villages in Normandy, for example, it was believed that the winning parish would secure the better apple crop that year. Another theory, put forward in 1929 by W. B. Johnson, is that the spherical ball for many early civilizations symbolized the sun. The captured ball represents the sun brought home to promote the growth of crops. The word

soule

, some linguists believe, may in fact derive from

sol

, the Latin word for sun.

In Orkney, there are similar long-standing beliefs that a win for the Uppies means a good potato harvest, whereas a win for the Doonies means the fishermen can expect a bountiful run of herring. To this day, Uppies will tell you that the potato blight that brought famine to the islands in 1846 began when the Doonies won the ba' that year and continued until 1875, when the Uppies finally broke their losing streak. That year, an old man was heard to comment, “We'll surely hae guid tatties this year, after the ba's gaen up.”

I

t was just past noon on New Year's Day when the first spectators began to assemble on the sandstone steps of St. Magnus Cathedral. They staggered out of doorways and alleys, bundled in thick overcoats and shielding their tired eyes from the sun cresting above the glazed rooftops. The whole town, myself included, was still shaking off the dog that bit us at the previous night's Hogmanay festivities, highlights of which included the requisite bagpipe brigade and the ceremonial passing of countless bottles of Famous Grouse. I staked out a choice spot along the cathedral wall next to the Mercat Crossâthe spot from which the ba's been thrown up for the past 200-plus years.

The sound of battle cries soon emerged from Albert Street as the Doonie players marched up from the waterfrontâ70 or so men of all ages, from 16 to 70, ready to do their part to tilt the cosmic balance back to the sea. The uniform of choice was a favorite, game-worn rugby shirt, a pair of old jeans, and steel-toed work boots. Experienced players had duct-taped their jean bottoms to their boots to deny their opponents a good handhold during the scrum. From the opposite side of town, down Victoria Street, came the Uppie contingent, prepared to push their supremacy into a new decade. Though deadly serious, the effect was pure theaterâthe Sharks and the Jets ready to rumble.

Reaching the cross first, the Doonies locked themselves into a tight mass, arms raised above their heads or placed around their mates' shoulders to keep them free to catch the ba'. Graeme stood up front taunting his opponents good-naturedly as they infiltrated and jostled for position like solid and striped billiard balls arranging themselves for the break.

Davie Johnston appeared from inside the cathedral with the ba' nestled safely in the crook of his arm and strode proudly to the base of the town cross. He was dressed to play, ready to jump into the fray right behind the ba'. He greeted teammates and surveyed the crowd below that had swelled to several hundred and filled in on all sides of the players. As the clock on the church tower inched toward the traditional hour of one, people began to whistle and cheer with anticipation.

“Go Uppies!” “Come on, Doonie boys!”

With the first loud clang of the church bell, Davie held the heavy ball high and lobbed it into the street below.

Arms shot up as the ba' was caught and instantly swallowed into the deep maw of the pack. The scrum surged and heaved as the two sides tried their best to gain first ground. Old codgers who in years past would have been in the eye of the storm ran around the outside where they coached and rallied their sons and grandsons.